THE NEW REFORM OF CHINA’S LAY ASSESSOR SYSTEM

Chen Xuequan & Tao Langxiao

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. THE CAUSES OF CHINA’S NEW REFORM

A. The Nominal Role of Lay Assessors

B. Improvements to Democracy and the Rule of Law

III. MATERIAL CHANGES IN THE NEW LAW

A. Building a New Selection System for Lay Assessors

B. Learning from the Common Law Jury System

C. Supporting Lay Assessors’ Duty Performance

IV. PROBLEMS WITH APPLYING THE NEW LAW AND SUGGESTIONS TO OVERCOME THEM

A. Public Awareness and Confidence

B. Dissenting Opinions in Judgments

C. Specifying the Fact-law Distinction

V. CONCLUSION

Lay participation in China’s judicial work has malfunctioned for decades, with lay assessors playing only nominal roles in trials. Aiming to solve this problem and improve judicial democracy, China issued the Law of the People’s Republic of China on People’s Assessors on April 27, 2018. The new law has made significant changes to China’s lay assessor system, but there are problems hindering the targeted improvement of judicial democracy. This article analyzes these problems based on a public survey and interviews of both judges and lay assessors, in combination with other significant findings of prior studies, and provides suggestions on the further improvement of judicial democracy in China.

I. INTRODUCTION

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the lay assessor system, popular in many civil law countries, has been adopted by China’s Mainland to guarantee its people’s democratic participation in judicial work. The lay assessor, also termed the people’s assessor or people’s juror, used to share the same authority as the professional judge in a collegial panel: they voted equally on all issues of fact and law in the case. However, this system has malfunctioned for years, with lay assessors playing only nominal roles in trials, expressing no independent thought, unthinkingly following the professional judges’ orders or opinions, and contributing little to deliberations.

To tackle this problem, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) proposed, in 2014, to reform the lay assessor laws. The National People’s Congress then authorized the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) to formulate the Pilot Program for the Reform of the System of People’s Assessors, which began in 2015. Fifty courts were selected across ten provinces as pilots for the reform experiments. Based on experiences from the three-year pilot program, China drafted the Law of the People’s Republic of China on People’s Assessors (hereinafter referred to as the New Law), which was enacted on April 27, 2018. The New Law implements the most extensive changes ever made to China’s lay assessor system. For instance, it establishes random selection for lay assessors, provides more allowances and protections for the performance of duties by selected lay assessors, and combines the traditional lay assessor mode with the jury mode of common law countries. In April 2019, the SPC published the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on the Law of the People’s Republic of China on People’s Assessors (hereinafter referred to as the SPC Interpretation), which reinforces these newly formed mechanisms.

Very few English articles have considered China’s lay assessor system, and most were written before 2018, with none examining the New Law and recent changes. Though many Chinese articles have recently introduced and analyzed the New Law, most focus on interpreting specific clauses, with none comprehensively researching the resultant changes in the Chinese justice system. This article aims to fill these gaps by examining the recent history of and current situation in China’s lay assessor system. The next section summarizes the background to and reasons for China’s new reform of the lay assessor system. The third section then introduces the changes made by the New Law and analyses their practical influences. The fourth section researches the problems with applying the New Law and make suggestions on how to overcome them. According to our findings from an online survey of 5,220 Chinese citizens, the public seriously lacks awareness and confidence in the lay assessor system. To improve the situation, advertising the system in an encouraging way would be more effective than imposing sanctions. Besides, even though there is no ‘professional assessor’, the heavier caseload may still force judges to rush the deliberations, risking the substantiveness of lay participation. Disclosing the dissenting opinions in judgments could preclude the problem in a more fundamental way. Furthermore, the fact-law distinction in cases tried by seven-member collegial panels is not clarified sufficiently. We suggest that the legislative gaps in making the list of facts need to be fulfilled. The fifth section concludes.

II. THE CAUSES OF CHINA’S NEW REFORM

China’s lay assessor system has malfunctioned for decades: the lay assessors, who represent ordinary citizens, seldom substantially participate in trials and decision-making processes in the cases. In recent years, China has striven to enhance democracy and the rule of law. Against this background, the public’s higher expectation for democracy and the CPC’s desire to improve judicial probity and credibility were root drivers of the new reform.

A. The Nominal Role of Lay Assessors

Prior to the new reform, the lay assessor system was mainly regulated by China’s criminal, civil, and administrative procedure law and the Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress regarding Perfecting the System of People’s Assessors of 2004. Under these laws, a collegial panel could have three, five, or seven members who are all professional judges or include a combination of professional judges and lay assessors. A collegial panel combining judges and lay assessors has jurisdiction to try a first-instance criminal, civil, or administrative case under the ordinary procedure. The number of lay assessors shall be no less than one-third of the total panel number. In practice, the three-member collegial panel most often has one professional judge and two lay assessors. Except that they could not be the presiding judge (which remains the case), lay assessors had the same decision-making power as professional judges. They were free to comment on fact-finding or the application of the law and had the right to vote independently. In theory, this system can provide judicial democracy because it allows ordinary people to freely apply their opinions and views about justice to cases. It is supposed to operate better than the common law jury system, which only gives jurors voting rights on factual issues.

However, the practical operation of China’s lay assessor system is seriously problematic. Although the number of ordinary procedure cases tried at first instance by collegial panels with lay assessors increased to 71.7 percent in the first half of 2013, a number of lay assessors were playing nominal roles by following judges’ directions in court. It is national wide recognized by the legal practitioners that the lay assessors play only nominal roles in practice. To research on the seriousness of the problem, the authors interviewed some experienced lay assessors. The authors visited two local courts, one in Qingdao City and the other in Shenyang City, to find the names and contact details of their former lay assessors who used to participate in trials before 2018. The authors then contacted these lay assessors to enquire whether they were willing to be interviewed by telephone. Finally, the authors interviewed five lay assessors (on condition of anonymity) who served in the two local courts before the new reform. The following illustrative conversation is taken from one of these interviews:

Question One: Could you please introduce yourself and share your experience as a lay assessor? Answer One: Yes, I am willing to help. I am 58 years old this year and have been retired for eight years from a high school teacher position. I worked as a lay assessor in the local court (Qingdao City) for about eight years, from 2008 to 2015. I heard about the lay assessor position from a friend who works in the court and then applied individually to the court for the position. They reviewed my materials and granted me the opportunity one month after the application.

Question Two: Did you undertake a training process? How about the caseload and payment? Answer Two: Yes, before starting the work, I took classes and exams provided by the court. With judges and other lay assessors, I tried around 150 to 170 cases annually, but the payment was only about 700 yuan (100 US dollars) per month.

Question Three: Did other lay assessors get so many cases a year? Answer Three: No, as far as I know, only about five lay assessors were constantly working for the court. I guess that other lay assessors never showed up.

Question Four: What kind of trials were you involved in?Criminal, civil, or administrative?What did you do for these trials? Did you review case documents before trials? Did you ask questions to the parties in court? Answer Four: Most of the cases I tried were civil and a few were criminal. Before trials, I seldom read the documents because of the time pressure. In court, I listened to the parties and the presiding judge, but seldom asked questions.

Question Five: Did you vote based on your own opinions in deliberations? Did the judge explain the law to you? Did you ever vote against the presiding judge on the final decision?’ Answer Five: In deliberations, I followed the presiding judge’s opinions. Many cases were too complicated, and the time was too limited, so it is impossible for me to figure out all the details, let alone vote on my own. Some very nice judges explained the facts and law to us, but most judges were too busy to talk much in deliberations. I never voted against the judges because I believed in their professional ethics, and I was afraid that they would be annoyed by me.

The other four interviewees noted the similar phenomenon of most cases being assigned to several ‘professional assessors’ who became fixed assistants of the judges to rush through the caseload. Contrary to the theoretical assumption, Chinese lay assessors played a nominal role, which constitutes illusory democracy. The reasons for this significant problem were threefold.

First, the selection mechanism for lay assessors was problematic. Before the new reform, local courts had absolute control over the selection of lay assessors. The five interviewees became candidates through individual applications or recommendations by certain people’s organizations, but none were aware of the courts’ selection process, which demonstrates a lack of transparency and arbitrary use of discretion. Zhang Jiajun showed that high proportions of lay assessors are CPC members, urban inhabitants, and older citizens, and so are unrepresentative of the wider population. For efficiency, the courts typically select lay assessors from certain backgrounds, such as employees from residents’ committees or village committees, retired national staff, and family members of court employees. Such persons are time-flexible and eager to receive payment for serving as lay assessors, which makes them more amenable to judges. Consequently, many courts largely refused to select lay assessors from among ordinary citizens and instead hired ‘professional lay assessors’ to facilitate managing their heavy caseloads. Three of the five interviewees were so-called ‘professional assessors’ and regularly chosen by the courts to participate in trials. According to them, some other lay assessors were not even allocated to a case during their term. The distribution of the caseload among lay assessors was intentionally uneven.

Second, there was inadequate support for lay assessors’ participation. For instance, most courts offered only a small allowance for lay assessors. As reported in the interview quoted above, the allowance for a ‘professional assessor’ was much lower than the local average payment. Consequently, ordinary citizens with jobs were reluctant to be lay assessors since their regular salary would be replaced by an uneven payment. Another issue was that judges did not take lay assessors’ participation seriously. Even though all lay assessors completed a training process before start working, the heavy caseload and the complex nature of cases did not allow them sufficient time to form independent decisions. Besides, the judges were usually too busy to explain the detailed facts and laws to them, and sometimes even deprived them of the opportunity to deliberate. Consequently, for most cases, they could only follow the decision of the presiding judges in the panels and sign the judgments or other documents in accordance with the judges’ requests.

Third, the laws assigned impossible tasks to lay assessors. Before the new reform, China’s lay assessors were required to decide as judges on issues of fact and law in all cases. Paradoxically, lay assessors without legal knowledge were required to apply the law as professional judges. The five interviewees reported seldom expressing their own opinions and never voting against the judges, whom they considered more professional and authoritative. It is irrational to expect lay assessors, who rely on common sense, to effectively adjudicate cases involving complicated legal issues.

B. Improvements to Democracy and the Rule of Law

The improvements to China’s democracy and legal environment provide a social basis for the new reform. China was a feudal country from 475 BC to the 1840s: longer than any other country in history. From the 1840s to 1949, it suffered wars as a semi-colonial and semi-feudal country. Only after 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was formally established, could it begin to build its economy and justice system. Since launching economic reform and opening-up in 1978, China has gradually changed from ruling by people to ruling by law. A socialist system of laws with Chinese characteristics has now been established and is constantly being refined in pursuit of perfection. Human rights protection and the rule of law have been enshrined in the constitution and most programmatic documents.

With the diffusion of the Internet and social media, there are now more online and offline discussions and criticisms of controversial cases or judicial behaviors, reflecting Chinese citizens’ deeper understanding of the law and higher needs for democracy and justice. Sacrificing democracy and individual rights for judicial efficiency is no longer workable in China. In the past five years, the SPC circuit courts have redressed many miscarriages of justice. Relatedly, the purpose of building a ‘trial-centered’ judicial system is emphasized by advancing the independence of each collegial panel and establishing a responsibility mechanism to forbid external officials’ intervention.

In China, the lay assessor system serves both a legal and political purpose, as citizens’ participation in judicial activities constitutes an essential aspect of political democracy. In 2014, the CPC formally expressed the aim of building the rule of law China, toward which reform the lay assessor system was considered a necessary step. In conjunction with improvements to China’s legal and social environments, the CPC pushed the process of reviewing problems in the lay assessor system and improving the quality of lay participation.

III. MATERIAL CHANGES IN THE NEW LAW

The implementation of the New Law in China’s Mainland is the central achievement of the new reform. This section examines the three main material changes it introduced.

A. Building a New Selection System for Lay Assessors

The New Law adjusts the basic requirements for being a lay assessor to ensure better representation of the interests of ordinary citizens. One change is raising the minimum age from 23 to 28 years old, which is more consistent with the general minimum age for being a judge or a public prosecutor. In China, judges and public prosecutors are required to work as assistants in judicial organs for at least five years after achieving their bachelor degree, meaning most are around 28 years old before dealing with cases independently. Consistently, raising the minimum age should ensure that lay assessors are more mature and have richer life experiences, better equipping them to cooperate with judges and exercise their adjudicative power impartially. Ultimately, raising the minimum age strengthens the public credibility of judicial work.

The New Law also established a three-tier random selection system for lay assessors, aiming to ensure that the lay assessors in each collegial panel represent the real interests of ordinary people, rather than the court’s interests. First, lay assessor candidates are randomly selected from the list of permanent residents under the local court’s jurisdiction by the administrative organ of justice and the local court. The number of candidates should be more than five times the number of people’s assessors to be appointed. The two judicial organs subsequently examine the candidates’ qualifications and solicit their opinions. Second, the lay assessors are randomly selected from among the candidates who passed the qualification examination. The Standing Committee of the People’s Congress at the level of the local court will officially appoint these lay assessors, as requested by the local court’s president. A new swearing-in ceremony has been introduced for officially appointed lay assessors, so as to enhance their sense of formality and responsibly. Third, when forming the collegial panel for a case, the lay assessors should be randomly selected from the court’s list. In combination, the three tiers are intended to remove the court’s control over lay assessor selection and forbid the hire of ‘professional assessors.’ Until the end of 2019, nearly all courts have completed their random selection of candidates, confirmed candidates’ opinions through phone calls or text messages, and published their final lists of lay assessors online.

Although establishing random selection is a noteworthy improvement, the change is not fundamental because the traditional selection method is preserved, which leaves some scope for court control. The New Law still allows courts to select some lay assessors pursuant to individual applications and organizations’ recommendations. However, the number of lay assessors generated through this method shall not exceed one-fifth of the quota of lay assessors. It should be recognized that introducing an entirely random selection would be difficult in the initial stage of reform. For instance, some lay assessors suddenly quit their job or abandon trials, leaving little time for courts to find substitutes. Thus, courts usually choose some time-flexible lay assessors as substitutes in case selected lay assessors are not promptly available. Allowing up to one-fifth of lay assessors to be selected through the traditional method should be regarded as a temporary approach in the transitional period of reform, to be gradually replaced by fully random selection.

The New Law also introduces the first mandatory quota for lay assessors. Previously, each local court decided its own quota of lay assessors based on the caseload in its jurisdiction. To reduce the inconsistency in different jurisdictions, the New Law stipulates that the quota may not be lower than three times the number of the court’s judges. Based on this quota requirement and the approximate number of 123,500 judges as recorded at the beginning of 2019, China will need at least 370,500 lay assessors.

B. Learning from the Common Law Jury System

The most controversial change in China’s new reform is its application of the jury system’s fact-law distinction to seven-member collegial panels. Under the New Law, collegial panels shall comprise either three or seven members. In a three-member panel, lay assessors and judges will continue to decide together on all issues of fact and law. However, for a seven-member panel, comprising three judges and four lay assessors, the New Law mandates that lay assessors can only vote on factual issues; although lay assessors may comment on the application of laws, only judges retain the right to vote on legal issues. Unlike in the jury system, the three judges can also vote on issues of fact. The jurisdiction of the seven-member collegial panel is limited to four kinds of cases of special importance. First, criminal cases with great social impacts where fixed-term imprisonment of not less than ten years, life imprisonment or the death penalty may be sentenced; Second, public welfare lawsuits filed in accordance with the Civil Procedural Law of the People’s Republic of China and the Administrative Litigation Law of the People’s Republic of China; Third, cases involving land requisition and house demolition, ecology and environment protection, and food and drug safety, and with great social impacts; Fourth, other cases with great social impacts.

By re-allocating adjudicative powers in the seven-member collegial panel, China is combining the traditional lay assessor system with the jury system developed over many years in common law countries. The jury system is regarded as integral to democracy and human rights protection in the US, UK, Australia, and many other common law countries. In general, the jury’s role is restricted to fact-finding and the judge only applies the law. For instance, in a criminal case, after hearing all the evidence and debate, the jury gives a verdict on whether or not the defendant is guilty; the judge then applies the law to acquit or sentence the defendant, relying on the jury’s decision. This fact-law distinction has been partially adopted in China’s seven-member collegial panels. By limiting the four lay assessors’ adjudicative power to factual issues, the problem of lay assessors’ questionable ability to decide on legal issues is resolved. However, contrary to the jury system, the three judges can also vote on uses of fact. This innovation is intended to ensure the consistency of judgments, since the legislature feared that lay assessors alone might reach novel decisions that harm judicial credibility.

Overall, the New Law makes no changes to the workings of the three-member collegial panel. Consequently, the traditional lay assessor system without the fact-law distinction still dominates China’s judicial work, as most first-instance cases in the ordinary procedure are adjudicated by a three-member collegial panel. The traditional mode is preserved to maintain the comprehensive democratic participation of lay people in most cases where the relevant laws are easily understood. Besides, lay assessors are educated about the law through their participation; by discussing their experiences with family members and friends, lay assessors can also educate other ordinary citizens about the law and judicial work. Moreover, traditional lay participation, in most cases, would relieve judges from the burden of increasingly heavy caseloads, with only one professional judge required on each panel.

C. Supporting Lay Assessors’ Duty Performance

The New Law provides a series of new guarantees for lay assessors regarding workload balance, improved benefits, and the restriction of judges’ power, all designed to enable them to perform their duties.

First, the New Law imposes constraints on the term and workload of each lay assessor, thereby further preventing the generation of court-hired ‘professional assessors.’ Although the five-year term is unchanged, the New Law adds a restriction: ‘In general, a people’s assessor may not be reappointed’. Before the new reform, some lay assessors served consecutive terms and became familiar with all the court officials. This led to them being overly submissive to judges and, thus, representing the courts’ interests, rather than those of ordinary people. The new term restriction will reduce this risk. Another prior problem was the excessive caseload of each lay assessor. To solve this problem, the New Law requires each court to determine and publicly announce the upper limit to the number of cases in which each lay assessor participates each year. Article 17 of the SPC Interpretation further explains that the upper limit must be lower than 30 cases. For instance, as a pilot court for the reform from 2015, the Beijing No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court announced an upper limit of 20 cases annually for each lay assessor in 2016. In practice, the court successfully controlled each lay assessor’s workload in 2016, with no lay assessor participating in more than 18 cases and an average of 4.5 cases per lay assessor.

Limiting the caseload of each lay assessor also mitigates the risks from retaining the traditional selection method. Since up to one-fifth of lay assessors can still be selected pursuant to individual applications and organizations’ recommendations, the courts might be inclined to overly use traditionally appointed lay assessors as substitutes when randomly selected lay assessors fail to attend trials without warning. Accordingly, the caseload limitation should further prevent courts from converting certain lay assessors into ‘professional substitutes.’

Second, the New Law imposes duties on the presiding judge to appropriately facilitate and guide lay assessors’ participation:

The presiding judge shall perform the obligation of guidance or prompt related to the trial of cases, but he or she may not obstruct people’s assessors’ independent judgment of cases. In the deliberation of a case by a collegial panel, the presiding judge shall make necessary interpretations and explanations to people’s assessors on the fact-finding, rules of evidence, legal provisions and other matters, and issues to which attention should be paid.

This new provision emphasizes rebalancing the uneven authority between judges and lay assessors. Since judges’ performance assessment system still considers case settlement rate as a central criterion, judges are always pressured to drive procedures toward prompt completion, often causing the quality of lay assessors’ participation to be ignored. This problem may be somewhat alleviated by the imposition of affirmative duties on the presiding judge to serve lay participation.

Finally, articles 28 to 32 of the New Law elaborate on the legal protection and benefits of lay assessors. The personal and domicile safety of lay assessors are now protected. From a financial perspective, courts are required to pay subsidies, travel expenses, meal costs, and other benefits to lay assessors. All of these are covered by the business funds of courts and the administrative organs of justice, which are financially guaranteed by local governments. The New Law also forbids the employers of lay assessors from reducing their salaries or removing their benefits. If an employer violates this prohibition, the courts have the authority to order the employer or the superior department of the employer to correct their behavior. These protections of the rights and benefits of lay assessors should encourage them to participate actively in judicial work.

IV. PROBLEMS WITH APPLYING THE NEW LAW AND SUGGESTIONS TO OVERCOME THEM

The New Law undoubtedly brings unprecedented improvements to China’s lay assessor system. However, deep reform of the system has been inhibited by long-standing problems and deficiencies in the New Law itself. This study conducted an online survey of ordinary citizens and interviewed several judges and lay assessors to collect their views on the obstacles to implementing a more effective lay assessor system. It also draws on empirical research results from previous studies of renowned Chinese scholars. This section summarizes the problems from three perspectives and proposes suggestions to solve each one.

A. Public Awareness and Confidence

Citizens’ unwillingness to be lay assessors and participate in trials is an obvious obstacle to judicial democracy in China. In a study of a pilot court in 2015, only 134 of 500 randomly selected candidates (26.8 percent) agreed to be lay assessors; reasons for refusal included busy job, living too far from the court, and other personal reasons. During discussions on the New Law’s drafting, some judicial officials expressed disagreement with introducing random selection because citizens’ negative attitudes may burden court officers with repeated selection and correspondence to secure enough candidates. However, our survey suggests that China’s citizens are generally not equipped with even basic knowledge about the lay assessor system, which largely explains some citizens’ negative attitudes.

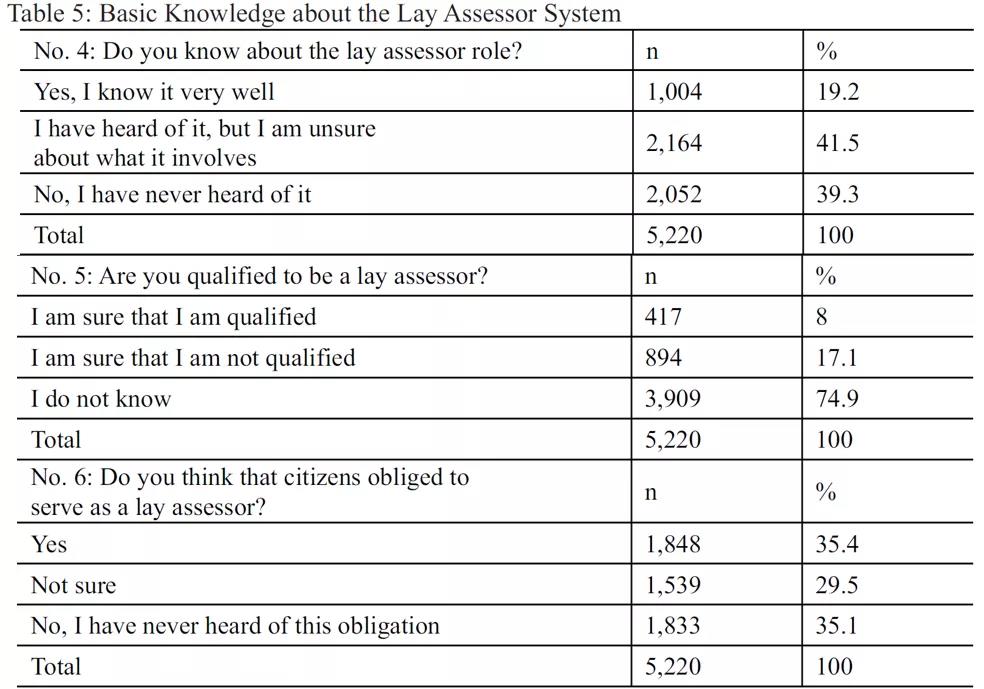

1. Online Survey. — This study researched the opinions of Chinese citizens about the lay assessor system. In December 2018, the authors published a seven-question survey online through Wen Juan Xing, a research survey collection platform in China. The questionnaire was open to all online users, intending to gather general public opinions about the lay assessor system from respondents of different ages and occupations. After one month, the authors had collected a total of 5,220 valid completed surveys. The survey was divided into three parts: the first two questions concerned respondents’ age and occupation type; the third and fourth questions probed their willingness to be and the impediments to them being lay assessors; and the fifth to seventh questions probed the extent of their knowledge about the lay assessor system. The content of these questions and the collected results, as analyzed through SPSS, are reported in the tables below.

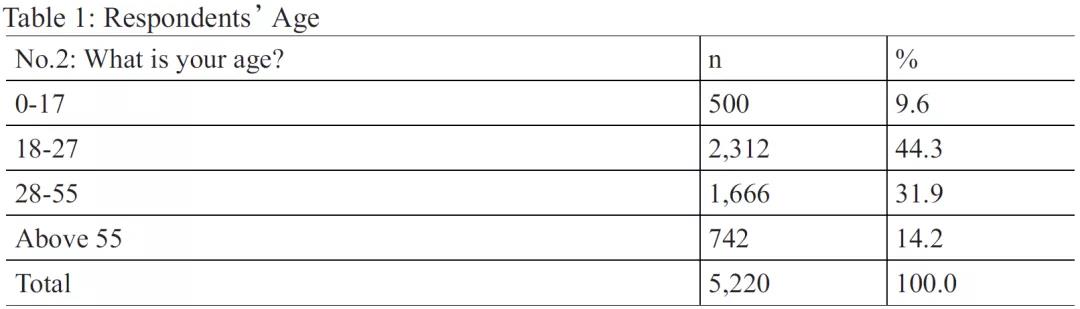

Age and occupation. As reflected in Table 1, the authors grouped respondents into four age brackets based on significant age milestones in China: 18 years old is the legal threshold for adulthood, 28 is the qualifying age for being a lay assessor, and 55 is the general age for retirement. About 53.9 percent of the respondents are juveniles and young people aged under 28, reflecting that younger generations are the major users of the Internet in China. Although they are not yet qualified to be lay assessors, their opinions could predict a future trend in China. By contrast, 46.1 percent of respondents aged 28 and above could represent the current situation.

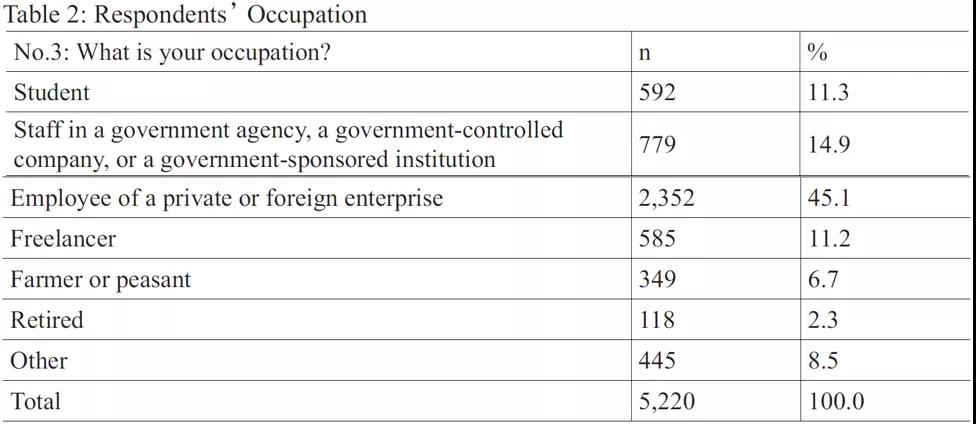

For occupation, the seven options represent the major occupation types in China. Except for indicating the representativeness and universality of our sample, the question is designed to enable analysis of whether citizens with government-related jobs know more about the lay assessor role and/or are more willing to serve as lay assessors.

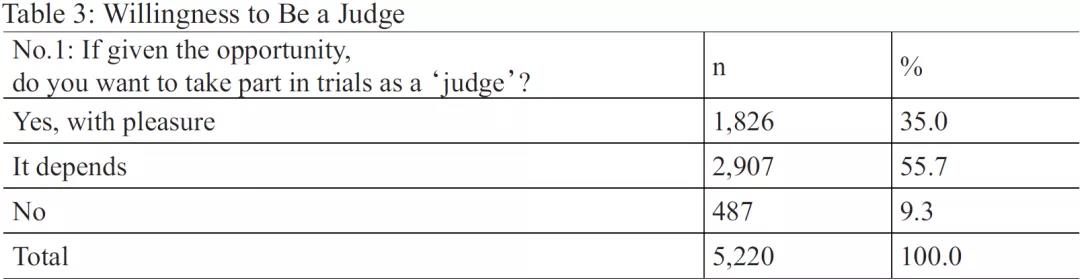

Willingness and impediments. Citizens’ willingness to take part in trials is reflected in the results reported in Table 3. The largest proportion of respondents (55 percent) reported an ambivalent attitude toward taking part in trials, while about 35 percent definitely wanted to participate and only 9.3 percent clearly did not.

When we cross-analyzed responses to this question with the age and occupation data, we found two remarkable results. First, in terms of age, the 28 to 55 group had the highest rate of negative responses (14.5 percent) and the lowest rate of positive responses (28.4 percent). Second, in terms of occupation, the two highest rates of positive responses were for students (44.6 percent) and staff in a government agency, government-controlled company, or government-sponsored institution (41.5 percent); these two groups also had the two lowest rates of negative responses (4.4 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively).

The above results suggest that Chinese citizens are not truly reluctant to take part in trials, as only a small percentage indicated they were unwilling to do so. However, conditional willingness was more common than unequivocal willingness. People aged 28 to 55 reported less willingness than the other age groups to participate in trials. Meanwhile, people studying or in jobs with some relation to the government are more willing to participate than people in other occupations.

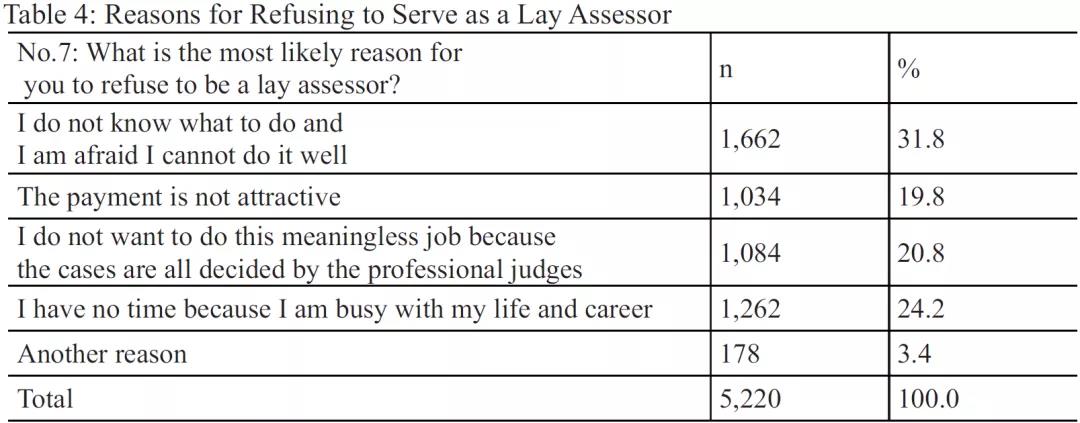

To find out the underlying reasons for citizens’ refusing to be lay assessors, the authors asked respondents which was the most likely reason for them to refuse. As reported in Table 4, the lack of clarity regarding the lay assessor’s job is the biggest obstacle (31.8 percent), followed by competing time commitments (24.2 percent), lack of confidence in the lay assessor’s democratic function (20.8 percent), and the poor rate of pay (19.8 percent).

Combining these results with those for the willingness question, it could be inferred that Chinese citizens are not truly reluctant to take part in trials but many may refuse because they lack basic knowledge about the lay assessor system. To test this inference, we next consider responses to the questions designed to explore how much people know about the system.

Basic Knowledge. The results reported in Table 5 reflect the extent to which citizens are equipped with basic knowledge about the lay assessor system. In total, 39.3 percent of respondents have never heard of the lay assessor position, and 41.5 percent are unsure what it involves. Moreover, 74.9 percent of respondents do not know whether they are qualified to be lay assessors. Despite the New Law stipulating that ‘any citizen has the right to serve and obligation to serve as a people’s assessor according to the law’, 35.1 percent of respondents deny knowledge of the obligation and 29.5 percent are unsure about it. The findings indicate that most citizens have very limited knowledge about the lay assessor system.

The online survey results add weight to the presumption that many citizens are not intrinsically opposed to participating in trials but may refuse to be lay assessors because they do not know what this role entails. Public awareness of and confidence in the lay assessor system are not sufficiently developed in China. Long-term court control over selection has limited lay participation in judicial work to a small group of people. Consequently, ordinary citizens whose interests are supposed to be represented by lay assessors lack basic knowledge about the lay assessor system, have little respect for lay participation, and thus largely refuse to be candidates or subsequently abandon trials.

2. The Appropriate Approach to Improve. — Considering the poor public awareness and confidence about the lay assessor system in China, it is crucial to adopt an appropriate approach to improve the situation. One view is that sanctions must be imposed on lay assessors who fail to perform their obligations, so as to eliminate their absence from trials and force lay assessors and the public to attach importance to lay participation. In most jurisdictions with a jury system, such as Hong Kong, a juror’s non-attendance or sudden withdrawal without a reasonable cause or the judge’s permission will constitute an offense liable to a fine or criminal contempt of court. However, the New Law in China does not impose any sanction on lay assessors’ failure to fulfill their obligations. We endorse this silence because imposing sanctions at a stage where most citizens have poor knowledge about the lay assessor position may easily lead to public dissatisfaction. Accordingly, the sanction approach is not currently appropriate.

Instead, this article suggests that China should adopt an encouraging approach. It is important that Chinese courts and relevant judicial organs strictly implement the random selection system required by the New Law, and make the selection and performance of lay assessors transparent to allow public scrutiny. It would also be beneficial to publicize in the media some typical cases in which lay assessors play distinct roles, allowing citizens of all ages and working in diverse jobs to understand the importance of lay assessors and recognize changes implemented by the new reform. The encouraging method has already started to yield promising results in big cities. In Beijing’s courts, for instance, the quota for lay assessor applicants was met only a few minutes after opening the online application portal, and news on the appointment and removal of lay assessors is accessible on the courts’ websites. However, improvements in enthusiasm have not been extensive, especially in rural areas, which suggest that a profound and fundamental change in China needs more constant and balanced encouragement.

B. Dissenting Opinions in Judgments

Although the New Law eliminates the possibility of courts hiring ‘professional assessors’, the risk remains that judges may marginalize lay assessors to achieve efficiency in settling cases. How to effectively lower this risk without disturbing case flow is a difficult problem untouched by the new reform.

Recently finalized reform of the judicial staff quota system commenced in May 2017 with the aim of further professionalizing China’s judges and prosecutors; it has intensified the caseload pressure for each judge. Only individuals who passed the judge assessment retained their positions with authority to try cases directly; the rest were demoted to support personnel in courts. This reform reduced the number of judges in China from 210,000 to 120,000, leaving each judge facing even greater caseload pressure, and thus aggravating the risk of neglecting lay assessors’ activities in pursuit of greater efficiency. For this study, the authors interviewed three judges (on condition of anonymity) who are serving in three different local courts in Beijing. Consistent with the five interviewed lay assessors, the judges asserted that substantive lay participation relies heavily on judges explaining complicated legal rules and seeking the opinions of lay assessors in deliberations. All three judges had encountered lay assessors who only expressed their confusion if directly asked whether they understood. Relatedly, none of the five interviewed lay assessors had insisted on asking questions or discussing a point when judges on the panel showed impatience. Though the New Law obliges judges to give proper guidance to lay assessors, the performance of this obligation is neither supervised nor inspected.

Generally, the judges’ interpretation of the law or guidance to lay assessors is given in the course of deliberation. However, the collegial panel’s deliberation is conducted in secret. Although the deliberation process is recorded, the transcript is not disclosed to either the parties or the public, who cannot, therefore, know whether the judges properly performed their obligation and whether the lay assessors expressed their views and voted independently. As one interviewed judge explained, ‘guidance to lay assessors is a matter of judges’ conscience.’ In a prior survey of judges’ decisions when lay assessors disagree during deliberations in a pilot court, 42 percent of judges reported that they would manage to persuade lay assessors, while 50 percent of judges would refer the case to a judicial committee for a final decision; only eight percent of judges would listen to lay assessors’ views and let the panel members vote on the final decision. These findings indicate that only a few judges respect lay assessors’ right to vote independently in deliberations, as required by law. Even after the new reform, the activities of judges and lay assessors in secret deliberations must be more tightly supervised to ensure substantive lay participation.

Given the foregoing discussion, this article recommends disclosing more judicial opinions, including dissenting opinions, in the judgment of the collegial panel, giving transparency to the products of deliberations. In China, a court judgment is written by the presiding judge and records the majority opinion of the collegial panel, excluding any dissenting opinion and omitting the voting result. It is traditional in civil law countries to exclude dissenting opinions from the judgment. Among the historical and institutional reasons for this tradition is the lack of precedential authority of prior case law and the prohibition of judge-made law. The major justification for retaining the tradition could be summarized thus: the judges who do not agree with the views of the majority exercise the right of expressing their disagreement, either generally or by dissenting opinions explaining the reasons for their disagreement, tends to bring discredit on the courts by advertising the fact that the conclusions reached in some cases are not the unanimous opinions of the court, and that the losing party would have been successful if the views expressed by the dissenting judges had prevailed.

The pursuit of certainty and the fear of losing public credibility thus deter the publication of dissenting opinions in civil law countries. This view has been challenged and criticized for centuries by common law countries, which value the power of open voting and dissenting opinions. On balancing the conflicts between transparency and unanimity, Charles Evans Hughes explained as follows:

When unanimity can be obtained without sacrifice of conviction, it strongly commends the decision to public confidence. But unanimity which is merely formal, which is recorded at the expense of strong, conflicting views, is not desirable in a court of last resort, whatever may be the effect upon public opinion at the time. This is so because what must ultimately sustain the court in public confidence is the character and independence of the judges. They are not simply to decide cases, but to decide them as they think they should be decided, and while it may be regrettable that they cannot always agree, it is better that their independence should be maintained and recognized than that unanimity could be secured through its sacrifice. A dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal to the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the error into which the dissenting judge believes the court to have been betrayed.

In recent years, the view that formal unanimity should be sacrificed to exhibit the independence of decision-making has attracted more supporters worldwide. Some modern civil law countries, like Germany and Spain, have started to disclose dissenting opinions in judgments, especially those of constitutional courts. In China, the Guangzhou Maritime Affairs Court, the Shanghai No.2 Intermediate People’s Court, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court, and the Beijing No.1 Intermediate People’s Court have all disclosed judges’ dissenting opinions and their brief reasons (limited to one or two sentences) in a few case judgments since 2000. Furthermore, since the beginning of the new reform, five courts in Beijing have included some concurring opinions of lay assessors in seven-member collegial panel judgments. These developments indicate a relaxing of ideological opposition to the disclosure of judicial opinions, including dissents, in civil law countries, and China is part of this trend toward accepting the full disclosure of judicial opinions.

To confine judges’ power and manifest the importance of lay assessors in China, it may be appropriate to disclose in court judgments the positions and reasons of lay assessors or judges who disagree with the majority. Since lay assessors and judges have the authority to vote, disagreements should be reflected in the final judgment. The majority could also respond to dissenting opinions in the judgment itself. While the secret deliberation process preserves space for all members of the panel to express their views and debate freely with one another, disclosing all opinions makes the judgment more persuasive and provides chances for the public to supervise whether the members of the panel, especially the lay assessors, have substantively exercised their judicial power by forming their own opinions, rather than merely agreeing with the presiding judge. In a national context, the public and scholars would be able to supervise whether the lay assessor system really worked by inspecting the number of dissenting lay assessors. Besides, the requirement to release voting results and the reasons for dissenting opinions will likely cause panel members to be more responsible when making decisions. Moreover, the important roles of lay assessors whose opinions are in the minority need to be seen and respected, which decreases the possibility of judges undervaluing lay assessors and ignoring their opinions. By revealing the central debates of deliberations, the public understanding of the careful process of decision-making will become more comprehensive, thus enhancing their trust in the independence of judges and lay assessors in panels and, subsequently, improving public confidence in judgments and the courts.

C. Specifying the Fact-law Distinction

The innovative introduction of the jury mode into China’s lay assessor system raises the problem of how to decide the fact-law distinction in cases tried by a seven-member collegial panel, in which the four lay assessors can now only vote on fact-finding matters. The New Law remains silent on how to distinguish issues of fact and law. In practice, this distinction is not straightforward. For instance, in criminal cases, the issue of whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty could be regarded by some as a simple question of fact, whereas others may consider this a legal matter because the decision-maker needs to apply the constitutive elements of a crime as written in legal codes.

In China, where to draw the line between fact and law relates to the extent of lay assessors’ discretionary power. Do lay assessors have the power to find a defendant not guilty based on their own sense of justice when the elements of a crime are clearly fulfilled? Or do they only decide on whether certain elements exist, without the power to vote on the question of guilt directly? The criteria and approaches to decide the fact-law distinction are essential. However, before the new reform, scholars in China have not sufficiently studied what the fact-law distinction should be. The result is a legislative gap in the New Law and practical difficulties for the workings of the seven-member collegial panel.

In modern legal systems, there are two major approaches to allocating adjudicative power between lay people and professional judges. One is the verdict mode adopted by most common law countries, such as the US and UK. Usually, a jury forms a general verdict based on the evidence exhibited by both parties and directions from the judge on the relevant laws. Alternatively, the jury may form a special verdict on a specific factual question submitted by the judge, such as whether the defendant is insane. These matters on which the jury decides are considered questions of fact; all other matters are regarded as questions of law, to be answered only by the judge. The other approach is the list of facts mode, employed in some civil law countries, such as Spain and Russia. Before the formal trial, the judges in the collegial panel list all the factual issues and hand this list to the lay assessors. The lay assessors’ power is limited to deliberating on the listed factual questions. Issues that are not listed are matters of law to be decided only by judges.

Although China’s New Law is silent on the matter, article 9 of the SPC Interpretation adopts the list of facts mode for all trials adjudicated by seven-member collegial panels. However, there are inconsistent aspects remaining to be resolved by further legislation. First, the obscure distinction between fact and the law must be addressed. Article 9 of the SPC Interpretation also specifies that the ‘hard-to-decide issues’ should be characterized as questions of fact, allowing both lay assessors and judges to vote. This indicates a move in the right direction of restricting judges’ discretionary power on making the list of facts. Yet the meaning of ‘hard-to-decide issues’ remains vague. For instance, should the parties and the four lay assessors be involved in the process of formulating the list of facts? Does ‘hard-to-decide’ refer to disagreements among the three judges only or among all the members? This article suggests that the opinions of the three judges and of the parties should be given weight in making the list of facts, given that the former is equipped with essential legal knowledge and the latter is significantly influenced by the result; however, the four lay assessors should be excluded from this process due to its potential to confuse them.

Second, the format of the list of facts needs to be standardized. Currently, some courts require lay assessors to simply write ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in response to each question, whereas other courts prefer the list to serve as a reference to help lay assessors to think. According to a judicial official interviewed for this study, the SPC and MOJ intend to draft a standard list of facts to unify and guide local practices, which may resolve the current inconsistency.

Third, besides the above problems that have already attracted great attention, the appropriate time to make the list of facts is more controversial. At present, the presiding judge usually prepares the list of facts at the pretrial conference, in the presence of the parties and lay assessors. This allows the parties to supervise judges’ neutrality in making the list and increases lay assessors’ familiarity with the case’s material facts, helping them to focus on the key issues in the trial. However, the pretrial conference usually concerns the exclusion of evidence. Allowing lay assessors to attend may distract them with evidence obtained by unlawful means, leading them to form a wrongful impression before the trial. Thus, after excluding lay assessors, the pretrial conference could be a proper time to make the list of facts. Lay assessors should only form independent opinions during the trial process itself, where admissible evidence is cross-examined by the parties.

V. CONCLUSION

In summary, the new reform of China’s lay assessor system has achieved great improvements, fostered substantive judicial democracy, and promoted the rule of law in China. Nevertheless, the New Law’s effective application is inhibited by the persisting influence of lay assessors’ long-standing nominal role, together with deficiencies in the legislation itself. This article recommends three measures to solve the existing problems: First, enhancing public awareness of and confidence in the lay assessor system through encouraging means, thus making ordinary citizens more willing to participate in judicial work; second, disclosing dissenting opinions of collegial panels to increase the transparency of lay participation in deliberations, thus enhancing public supervision of the substantiveness of participation; and third, specifying the process for making the list of facts, so as to clarify the fact-law distinction in seven-member collegial panels.

The new reform has introduced the greatest ever changes and innovations to China’s lay assessor system. The New Law combines the common law jury system with the Chinese traditional system on the regulation of seven-member collegial panels. It remains to be seen whether this combination is workable in China and can effectively change the long-standing nominal role of lay assessors. The detailed practical effects of this combination, which fall outside the scope of this article’s overall analysis of the New Law should be explored in future research. The New Law is merely one step in the reform of China’s lay assessor system. With reform now underway, the only appropriate approach is to continue making steady progress. In the future, ongoing judicial practice will inspire legislators to form a clearer roadmap of what can most suitably improve China’s judicial democracy. The innovative measures in the New Law and future attempts to develop them could provide valuable insight for other countries seeking to improve judicial democracy, especially those countries with a large population and limited judicial resources.