Liu Yueting

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. RELEVANT THEORIES

A. The Division of Labor and the Applicability of the Principle of Reliance

B. The Criminal Policy and the Applicability of the Principle of Reliance

II. BASIC INFORMATION ON RESEARCH DATA

A. Research Purpose

B. Temporal and Geographical Scope of the Study

C. Survey Respondents

III. DATA ANALYSIS

A. Data Analysis for Question One

B. Data Analysis for Question Two

C. Data Analysis for Question Three

D. Data Analysis for Question Four

IV. SUMMARY OF DATA ANALYSIS

This empirical legal study focuses on the application of the principle of reliance in medical malpractice in China. Given the differences in background, knowledge, and experience, during the interactions between the application of medical laws and clinical practice, legal and health professionals can have different practical ideas and perspectives regarding the medical division of labor and supervision as well as the application of the principle of reliance. Therefore, an empirical legal study is necessary to gain insights into this issue through the objective analysis of statistics as well as the analysis of the related legal literature and judicial decisions. The results of a survey conducted in China show that most participants had relatively high tolerance toward a medical negligent offender. Nevertheless, Chinese legal professionals must accept the application of the principle of reliance in medical malpractice. Through the survey and objective analysis of statistics, the author found that although the judicial and medical groups encounter the same problems, they have very different perspectives and attitudes.

I. RELEVANT THEORIES

The principle of reliance originated in Germany and played a role in traffic accident cases; with induction, deduction, and repeated argumentation in the scholarly community, it has gradually become a theory for decriminalizing negligence in traffic accidents. In the course of an actor’s collaboration with others to maintain the normal operation of social activities, the actor relies on the others’ actions, which comply with the existing laws, social norms, and rules of conduct. In cases where harmful consequences sustained by an actor are caused by an improper act of another actor, and there exists factual causation between the harm and the act, objective imputation does not apply as long as the reliance between the two actors is of social relevance.

The principle of reliance is fundamental to the formation and development of division and collaboration of labor in modern society. With the granular division of labor, modern society is progressively becoming the ‘society of strangers’, which has also begun to change our way of living. In the society of strangers, the interactions among people, including those in economic activities, rely on trust. There is no modern life without this reliance. As a necessary condition for the development of modern society, the principle of reliance together with its theoretical constructs exhibits an increasing scope of applicability.

The increasing applicability of the principle of reliance is mainly driven by technological advancements in human society and the accompanying division of labor. Only when the division of labor reaches a certain degree, people from different organizations can tolerate certain risks resulting from the division of labor, or even recognize the social relevance of some potentially harmful acts. These acts of social relevance, despite their inherent risks, are not deemed punishable. The principle of reliance is just a criterion used to determine whether or not a potentially harmful act is tolerable. Thus, the criterion for determining the applicability of the principle of reliance is the social relevance of the acts. Further, the criteria for determining the social relevance of an act include the capacity of conduct of the actor (for example, the ability of care), the risk inherent in the act, and the consequent harm(s) of the act. The risk inherent in the act is the most important criterion. The necessity of social defense is the main criterion to determine the degree of the risk inherent in an act. The degree of risk inherent in an act is defined based on the degree of division of labor, the level of economic and social development, cultural advancement, and the particular conditions and policies at the site of the act. An application of the principle of reliance leads to the mitigation of the penalty. The following is a detailed analysis of the relationship between the principle of reliance and the division of labor and criminal policy.

A. The Division of Labor and the Applicability of the Principle of Reliance

The premise underlying the division of labor is the ‘rationalized production’ by social organizations. Rationalized production does not necessarily mean mechanization, because not all ‘machines’ are made of metal or wood; they can be made of people, treated as mere components.

Thus, the division of labor is not completely synchronous with technological advancements but depends on the pace of the rationalization of production. Society has its mechanism of evolution. According to social evolutionism, technological advancement can be taken as a metaphor, because one tool does not produce another tool. This is very different from what happens in a species. If the society produces its own tools, and the reproduction of the species is accompanied by the reproduction of these tools, then the relationship of a tool to the society is logically comparable to that of a skeleton to a species. Technologically, efficiency indicates objectively visible differences, but this does not mean that technological, social, and ethical developments are synchronous.

Even though technology has advanced to a certain degree, the society, particularly the production rationalization-based division of labor, may not have developed to the same extent. In the context of division of labor, while some people engage in work that is necessary for sustaining human beings, other people can then be freed from the fetter of such work and engage in other work such as business service, scientific and cultural creation, and social management, thus increasing division of labor and improving productivity.

Thus, the division of labor has a counteraction on social production, making it more rationalized. The division of labor can be characterized into two dimensions: width and depth. The width of the division of labor refers to the number of labor specializations or the degree of labor separation and specialization. The widening division of labor is the process of increasing labor separation in basic production entities and social strata, a process accompanying the development of production activities in human society. The depth of the division of labor refers to the closeness of the relationship between production activities of different functions resulting from division of labor.

Therefore, ‘rationalized production’ means a certain width and depth of division of labor and manifests as economic vitality (market economy alone) and market separation. For example, by per capita GDP, economic development in East China is markedly better than in Central and West China. Thus, compared to Central and West China, East China has a higher degree of production rationalization or a deeper and broader social division of labor.

The premise underlying the reliance among members of different organizations is the division of labor. However, according to social evolutionism, the establishment of the principle of reliance, the process from the emergence of the concept of necessary reliance to the formation of reliance and the establishment of the principle of reliance as a basic principle of the division of labor, is not synchronous with production rationalization and division of labor. The development of the principle of reliance as a basic rule of action underlying production rationalization and the division of labor lags behind both of them. In the early stages of production rationalization or division of labor, social members may not have been confident in their pursuit of reliance, even though they did recognize its necessity. The actual situation may be the exact opposite: because of insufficient experience in social development and the inadequate division of labor, the unknown risks faced by human beings may have raised. Higher risks mean higher odds of harmful consequences and stronger reactions from the general public. Either based on rational or emotional speculation, people recognize the inadequate control with the existing system and almost consistently expect a large role of norms, particularly punitive norms.

Thus, the principle of reliance did not have a base for its existence as a jurisprudential criterion for tolerable risks. On the contrary, people may expect to subject harmful acts to a heavy penalty and impose a heavier duty of care on all acts necessary for social production, such as the duty of supervision. Even in a country or region with desirable levels of economic development and social production and a desirable scale of the division of labor, the principle of reliance may have not been recognized as a necessary basic standard of conduct in the context of the division of labor.

B. The Criminal Policy and the Applicability of the Principle of Reliance

The criminal policy refers to various measures established or implemented by legislative and judicial authorities to suit particular situations, particularly criminal conditions, in a country or region to prevent crimes and punish and reform criminals. ‘The priority is effectively preventing, controlling, and punishing crimes.’

The criminal policy in the sense of modern science is the totality of the values, strategies, and measures for dealing with and preventing crimes based on a scientific understanding of crimes. It is essentially a crime prevention policy. In national or regional judicial practice, the criminal policy usually has the effect of leading law enforcers to focus more on crime prevention, for example, many campaigns against illegal and criminal activities launched in China.

Judicial practice shows that the criminal policy influences the basic value orientation of the criminal justice system. Judicial justice activities are supposed to be carried out strictly in accordance with the law or following the principle of punishing crimes and protecting the rights and interests of citizens. However, under the criminal policy of ‘focusing on controlling and cracking down on crimes’, judicial practice tends to focus more on the cracking-down dimension than on the protection dimension, particularly the value orientation of limiting the rights of criminal suspects and defendants.

In other words, the criminal policy determines the basic value orientation of the criminal justice system. Particularly, it serves as a guide in judicial practice. The criminal policy guides the interpretation and implementation of criminal laws in criminal justice practice under the philosophy of crime prevention, thereby ‘maximizing the role of the criminal justice system of preventing crimes and protecting citizens’.

Thus, the establishment and application of the principle of reliance as a criterion of decriminalization is prone to the influence of criminal justice policy, or more precisely, it is a counteraction. This is because the principle of reliance is supposed to define and decriminalize acts involving tolerable risks, but this contrasts with the purpose of the criminal justice policy of ‘maximizing crime prevention and citizen protection’. Even in countries or regions in which the principle of reliance has been incorporated into criminal laws, the decriminalization function of the principle may be compromised by criminal justice policy.

In summary, the applicability of the principle of reliance and the mode of realizing its applicability are closely related to the division of labor and criminal justice policy. This article discusses the inherent relationships among three factors: the principle of reliance, the division of labor, and the criminal policy. This discussion aims at providing a conceptual and theoretical explanation for the empirical legal study of the applicability of the principle of reliance in modern China, particularly in the context of medical malpractice.

II. BASIC INFORMATION ON RESEARCH DATA

A. Research Purpose

From the application of the principle of reliance in criminal theory and law, and judicial precedents in Germany and Japan, the application of the principle is currently not limited to traffic accident cases and has been extended to all collaborative activities (for example, the collaboration between a surgeon and anesthetist and between a nurse and pharmacist).

In other words, the scope of the application of the principle of reliance includes not only the field of transportation but also other fields, such as medicine, food hygiene, and quality inspection. The root cause of this trend is social development and the increasing division of labor. With social collaboration gradually becoming the dominant production model of human society, the mutual supervision among individuals and the individual components of the social production machine has become critical. However, over-supervision has the opposite effect, as it impedes the development of social production. This affects the scope of the duty of supervision and the position of the principle of reliance within the criminal legislation. This is particularly evident in the division of labor in medical service institutions.

The participants of a medical service system include physicians, physician assistants, and medical technicians. These participants assume different duties, with physicians, in particular operating surgeons, assuming the heaviest duties. From the perspective that task assignment affects duty assignment, physicians perform the most critical tasks. To carry out their tasks, physicians have to be concerned about the tasks performed by other persons and cannot afford to neglect the tasks not performed by themselves. Nevertheless, other persons are also qualified to assume their respective duties. Thus, their acts can be relied upon. Therefore, under the principle of reliance, physicians are not liable for the negligence of other persons.

However, medical services are inherently harmful, risky, and complex, and the legal interests involved are the safety of life and the physical health of patients. Thus, the principle of reliance should be applied more discreetly in assessing the elements of medical negligence.

When medical laws and clinical practice mutually influence each other, legal and medical professionals may have different practical opinions and understandings concerning the division of labor, supervision of operations, and the principle of reliance owing to their different occupational positions, knowledge backgrounds, and practical experience. Thus, the theoretical investigation of the jurisprudential literature and legal precedents above is not enough. It is necessary to examine the different opinions and understandings of both professional groups through empirical legal analysis. This examination was performed using questionnaires and SPSS statistical techniques (student’s t-test, analysis of frequency, interaction, and variance). From an objective and neutral perspective, it aims to ‘identify values embedded in norms, substantive rationality in formal rationality, and natural laws in empirical laws and thus confirm the correctness of definite contents’. Here, ‘correctness’ refers to the practicability of criteria for determining the applicability of the principle of reliance, thus laying down a scientific-practical foundation for the establishment of criteria for the application of the principle of reliance in negligence cases. Through data analysis of a large sample, this study minimizes the possible deviation of statistical results from the general situation of social reality and avoids the predicament of ‘academic reasoning without data’, thus providing practical and theoretical criteria to investigate ideal and actual status of relevant questions and paving the way for further research on this topic.

B. Temporal and Geographical Scope of the Study

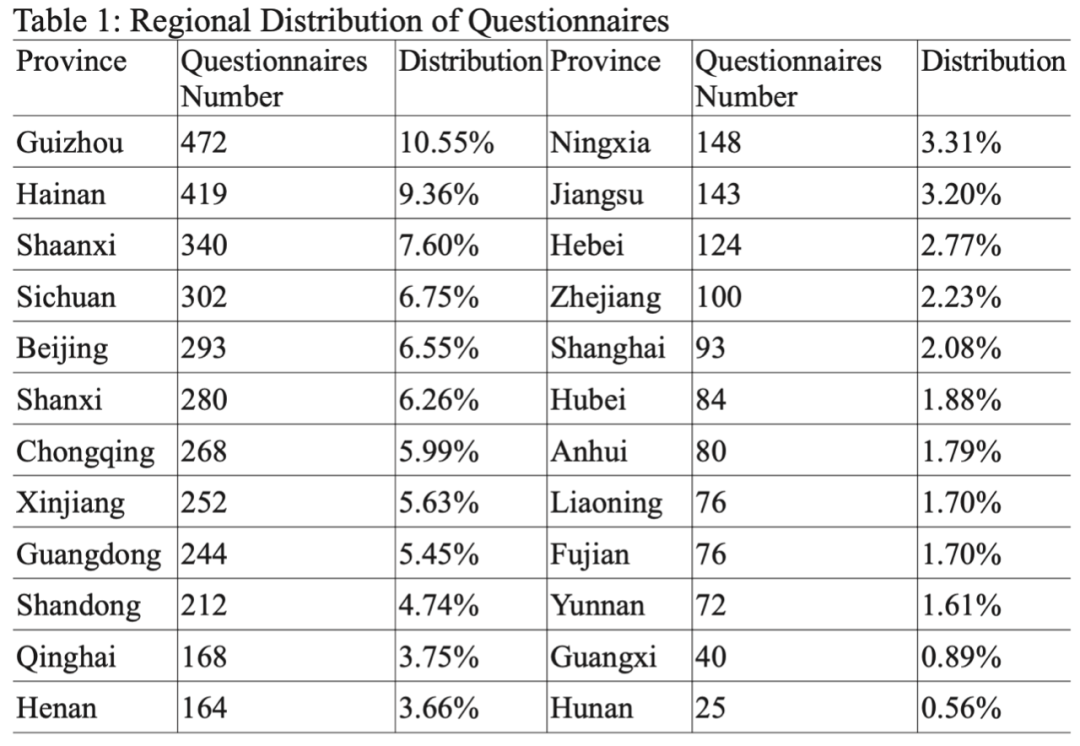

A survey was conducted across 24 of the 34 provincial administrative units (provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government) of China. The survey lasted 22 months (from August 1, 2017 to June 17, 2019). Table 1 shows the regional distribution of the questionnaires.

The provinces were grouped according to the level of economic development and the degree of influence of relevant policies. The grouping was based on the per capita GDP in 2012. This is because the most salient difference is that the coastal provinces are economically developed compared to the underdeveloped inland provinces.

C. Survey Respondents

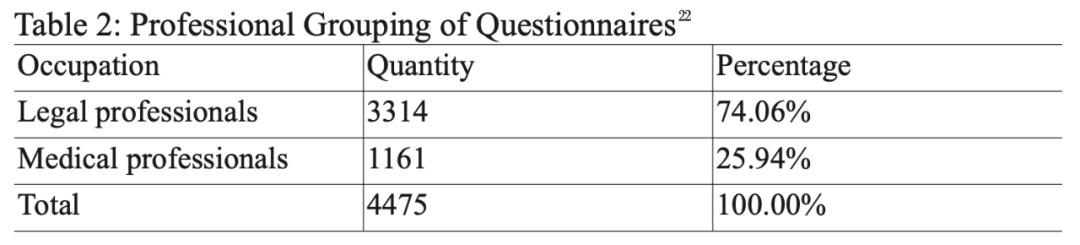

Questionnaires were distributed to 4,475 legal professionals (judges, prosecutors, and lawyers) and medical professionals (surgeons, pharmacists, nurses, and midwives) across 24 provinces. The survey collected 2,922 (74 percent) and 1,161 (26 percent) effectively completed questionnaires from legal and medical professionals, respectively, as seen in Table 2.

III. DATA ANALYSIS

A. Data Analysis for Question One

1. Question One and the Purpose of the Investigation.— Question One: A physician instructed a ward nurse to administer a vaccine to patient A using correct methods. The nurse wrongly administered the vaccine to patient B, resulting in a medical dispute. In your opinion, is the physician legally liable for medical negligence? If yes, is it a civil or criminal liability?

The first is the nature of the nurse’s service acts. A nurse’s medical service is her/his work of assisting the diagnosis and treatment performed by physicians, which is supposed to be performed in accordance with the instruction of physicians, and cannot be performed in the absence of physicians. During the provision of her/his services as a nurse (such as assisting in the assessment, diagnosis, and counseling of patients), she/he uses her/his expertise to identify, deal with, and report to physicians on the existing and/or potential health issues of the patients. They also assist physicians in performing medical operations according to the scope of nurse practice. Article 24(2) of the Hospital Working System and Job Responsibilities addresses the job responsibilities of nurse practitioners in the following words: ‘physicians participate in clinical nurse services, guide nurses to correctly follow the instructions of physicians, and solve problems in a timely manner’. Thus, a nurse service act involves assisting physicians while providing medical services. A nurse is supposed to stick to the scope of her/his job while providing services for patients.

However, owing to the characteristics of nurse services, a nurse performs her/his work independently and is responsible for the services performed according to the scope of her/his job. Although a nurse service act is essentially an act of assisting physicians’ medical service, it is performed independently, or there exists a division of duty between physicians and nurses. Thus, nurse service acts can be classified into two types: independent and subordinate. As for physician’s medical service acts, independent nurse service acts are ‘the nurse services performed by nurse practitioners according to their expertise and know-how’, while subordinate nurse service acts are ‘the medical services performed by nurse practitioners according to their expertise and know-how and the instruction of physicians’. Notably, however, medical service conventions vary temporally and spatially. Thus, the scope of independent and subordinate nurse service acts cannot be defined easily.

The second is physicians’ acts of instruction. Article 12(7) of the Hospital Working System and Job Responsibilities addresses the job responsibilities of medical practitioners in the following words: ‘physicians should earnestly follow various rules, systems, and technical operation standards, perform or instruct nurses to perform various important checks and treatments, and take strict precautions against errors’. Thus, subordinate nurse service acts must be performed according to the instruction of physicians.

The third is the purpose of investigation. Generally, a physician’s instruction must be explicit. However, whether or not a physician needs to observe an operation that she/he has instructed a nurse to perform depends on the possibility of the medical and health risk of the intended operation. If the medical operation the physician has instructed is an act of assistance in nature and is of high risks, she/he should supervise the performance of the instructed operation to ensure safety. This is particularly important for defining the physician’s duty of supervising the nurse’s administration of the injection in Question One. Based on the position, injections can be classified into intradermal (for example, skin test for penicillin allergy), subcutaneous (for example, inoculation in Question One), muscular, intravenous, lumbar, ganglion, intrapleural, and cerebellomedullary cistern injections. Injections may cause physical injuries, for example, pain, infection, artery occlusion, nerve injury, and vaccination failure. As an intrusive treatment, the injection should be administered as instructed by the physician; whether the physician needs to supervise the administration of the injection should be determined based on the risks of the injection. Generally, a physician is the one in charge of the dispensation of the medical services and must supervise all her/his assistants and their assistant medical services, which is jurisprudentially a matter of course.

However, in real-world hospital environments where there are not enough physicians to serve patients, nurses often administer injections independently after being instructed by physicians. In cases where such medical services ‘without due attention of physicians’ have occurred frequently and become (possibly unconscious) medical routines, physicians cannot be held liable, even though objectively, the duty of care has not been fulfilled. This is because, during the performance of these routine acts, a special reliance has been established between physicians and their assistants, and physicians can claim the principle of reliance for their support. However, ‘if it is unreasonable to preclude objective imputation’ by resorting to the principle of reliance in an organizational relationship based on certain clear facts, the physician’s liability for failing to fulfill her/his duty of care must be assessed. The definition of such medical routines or clear facts varies spatially and temporally and is subjective. This variation certainly affects the definition of the scope of subordinate nurse service acts and the physician’s duty of supervision.

2. Data Analysis. — The first is occupational differences in the perceived legal liability of the physician. According to the data, 30.8 percent of the legal professionals and 27.6 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.036; p

The second is the regional difference in the perceived legal liability of the physician. According to the data, 71 percent of the respondents from East China and 69.4 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the physician legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.235; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 70 percent of the legal and medical professionals in East, Central, and West China deemed the physician legally liable.

The third is the occupational difference in the perceived criminal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 6.8 percent of the legal professionals and 4.8 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.017; p

The fourth is the regional difference in the perceived criminal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 92.9 percent of the respondents from East China and 94.3 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.055; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 93.7 percent of the legal and medical professionals from East, Central, and West China deemed the physician criminally liable.

The fifth is the occupational difference in the perceived civil liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 27.5 percent of the legal professionals and 24.5 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.047; p

The sixth is the regional difference in the perceived civil liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 73.9 percent of the respondents from East China and 72.9 percent of those from Central and West China did not deem the physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.450; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 73.3 percent of the legal and medical professionals from East, Central, and West China did not deem the physician liable under the civil law.

B. Data Analysis for Question Two

1. Question Two and the Purpose of the Investigation.— Question Two: Before surgery, a surgeon requested an anesthetist to anesthetize patient A using correct methods. The anesthetist was not available. A nurse anesthetist performed the task as instructed, but on patient B. This resulted in a medical dispute. In your opinion, is the surgeon liable for medical negligence? If yes, is it a civil or criminal liability?

First, the independence of administering an anesthesia injection. Article 17(1) of the Hospital Working System and Job Responsibilities addresses the job responsibilities of medical management in the following words: ‘Anesthesia should be performed by certified anesthetists according to their authorized scope of clinical anesthesia, pain treatment, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation’. Thus, an injection administered by an anesthetist to anesthetize a patient is an independent act and does not need to be supervised by a surgeon. In other words, ‘an anesthetist and surgeon have different duties of care in their respective fields’. A surgeon is not allowed to administer anesthesia. The surgeon makes the final decision on whether and how to perform the surgery and assesses the overall risks associated with it. She/he has no authority to interfere with the anesthetist’s administration of anesthesia. The anesthetist may not refuse to collaborate with the surgeon unless the anesthetist deems the risk of anesthesia markedly higher than that of the surgery or the surgeon evidently incapable of performing the surgery. In the above exceptional scenarios, the anesthetist is more advantageously positioned than other participants of the surgery; if she/he performs anesthesia without considering the particular situations, criminal liability may arise, and she/he may lose the job, because her/his failure to fulfill her/his duty of care constitutes a special cause of contract termination. A nurse anesthetist is only allowed to assist in the administration of anesthesia, and her/his assistance must be supervised by the physician in charge or must be performed as instructed by an anesthetist.

Second, the purpose of the investigation. In the scenario presented in Question Two, the nurse anesthetist is not authorized to administer anesthesia but she/he does that given the request of the surgeon. Although the anesthetist is not available, the nurse’s act is an act of medical assistance and should be supervised by the surgeon. Thus, the following questions arise: Is the surgeon allowed to administer anesthesia? Has the surgeon fulfilled her/his duty of care for the abnormality of the nurse anesthetist’s administration of anesthesia (because normally anesthesia is supposed to be administered by the anesthetist)? The author answers both questions in the negative, which is jurisprudentially a common understanding of the medical practice in China.

However, the practical dimension needs to be considered as well. Anesthesiology was established only recently as a branch of medicine in China, as it was formally recognized as a second-level branch of clinical medicine only in 1983. The position of anesthetists and their independence in administering anesthesia in clinical practice in China are constrained by two factors, namely, resource inadequacy and delayed development of anesthesiology. ‘The anesthetist to surgeon ratio is 1:3 internationally, but only 1:6 in China.’ Further, the development of anesthesiology has been constrained by inadequate attention, several obstacles, and an incomplete fostering system. Understandably, in some hospitals, anesthesia may be administered by surgeons and not anesthetists. Thus, further investigation of the scenario for Question Two necessitates data on relevant actual situations.

2. Data Analysis. — First, occupational differences in the perceived legal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 56.6 percent of the legal professionals and 51.5 percent of the medical professionals deemed the surgeon legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.036; p

Second, regional differences in the perceived legal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 53.2 percent of the respondents from East China and 56.6 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the surgeon legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.024; p

Third, occupational differences in the perceived criminal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 16 percent of the legal professionals and 9.5 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal professionals tend to be more willing to hold physicians criminally liable compared to medical professionals.

Fourth, regional differences in the perceived criminal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 16 percent of the respondents from East China and 13.2 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.009; p

Fifth, occupational differences in the perceived civil liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 50.8 percent of the legal professionals and 53.7 percent of the medical professionals deemed the surgeon liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.088; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 48.5 percent of legal and medical professionals from East, Central, and West China appeared to hold the surgeon liable under the civil law.

Sixth, regional differences in the perceived civil liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 47 percent of the respondents from East China and 49.5 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the surgeon liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.097; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 48.5 percent of the legal and medical professionals from East, Central, and West China deemed the surgeon liable under the civil law.

C. Data Analysis for Question Three

1. Question Three and the Purpose of the Investigation.— Question Three: A surgeon performed a surgery on a patient using correct methods. The operating room nurse did not check the quantity of surgical gauze. After the surgery, it was found that surgical gauze was left inside the patient. This resulted in a medical dispute. In your opinion, is the surgeon liable for medical negligence? If yes, is it a civil or criminal liability?

First, the legal interpretation of foreign materials retained in the patient’s body. The scenario in Question Three involves the following questions: Is the principle of reliance applicable when the surgeon has a duty of supervising the nurse’s act? Is the nurse’s act of checking the quantity of surgical gauze an independent or subordinate act of nurse service?

Article 34(1) of the Hospital Working System and Job Responsibilities addresses the nurse service working system in the following words: ‘Scope of surgical check: all materials on the sterile table used during surgery. Time of check: before surgery, before closing a body cavity, after the closure of a body cavity, and after skin suture. Persons in charge of surgical check: scrub nurse, circulating nurse, and lead surgeon. The check should be performed by two nurses, one checking and the other recording. The check should be accurately recorded, with special attention paid to screws on special devices and the integrity of articles. Surgeons are not allowed to leave surgery until surgical materials are checked and recorded. Before closing a body cavity, the surgeon should take all materials out of the cavity and then check them. The lead surgeon should inform assistants and nurses of any materials placed deep inside a patient promptly, so that the assistants and nurses can remind the lead surgeon to take out the materials.’

Independent nurse service acts refer to operations performed by nurses independently according to their expertise, know-how, and experience, including nurse service evaluation, diagnosis, planning, measures, evaluation (measuring patients’ response to nurse service measures and evaluating whether they have achieved the intended effect and preset objectives), and recording.

Thus, in the scenario presented in Question Three, the nurse’s act of checking the quantity of surgical gauze is not an independent nurse service act and should be supervised by the lead surgeon.

Second, the purpose of investigation. A lead surgeon has the duty of supervising the entire course of surgery according to the relevant laws and regulations. However, in clinical practice, the lead surgeon may not be able to take care of the details of surgical material check, because she/he needs to personally perform an arduous surgery, follow complicated operational procedures, and handle many surgical devices and consumables (for example, sterilized cotton) and also needs to supervise nurse services and monitor the overall risks involved in the surgery (including the risk of anesthesia). Thus, based on the principle of the division of labor, the regulatory requirements are that the scrub and circulating nurses should perform the surgical material check and the lead surgeon should supervise the check by reminding and informing the nurses so that the heavy workload of the lead surgeon can be alleviated and the quality of the surgery can be guaranteed. However, according to the reasonable division of labor, in the scenario in which a small object is left inside the body of a patient, if a surgeon cannot predict the negligence and the nurses have fulfilled their duty of care, then the surgeon’s duty of care for the negligence must be precluded by the criminal law, or the surgeon does not have a duty of supervision for the small object, or the surgeon can claim the principle of reliance on the nurse for her/his support. If the surgeon is supposed to be capable of identifying a large object left inside the body of a patient but has not taken it out nor reminded the nurses to perform an accurate surgical material check nor supervised it, then the surgeon has failed to fulfill her/his duties of administering medical treatment and supervising the nurses. Thus, the surgeon cannot claim the principle of reliance on the nurse for her/his support, which is jurisprudentially a matter of course.

Whereas the theoretical justification mentioned above is reasonable, it is difficult to apply these criteria in clinical practice. For example, what is a large object? What are the criteria for determining whether a surgeon is capable of supervising surgical material checks while being occupied with a surgery? Whether the above theoretical reasoning is consistent with practical reasoning needs to be answered by using statistical data and empirical analysis.

2. Data Analysis. — First, occupational differences in the perceived legal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 70 percent of the legal professionals and 67 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.088; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 69.3 percent of legal and medical professionals from East, Central, and West China deemed the physician legally liable.

Second, regional differences in the perceived legal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 70.2 percent of the respondents from East China and 68.6 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the surgeon legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.280; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 70 percent of legal and medical professionals in East, Central, and West China deemed the physician legally liable.

Third, occupational differences in the perceived criminal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 19.2 percent of the legal professionals and 13.8 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal professionals tend to be more willing to hold physicians criminally liable compared to medical professionals.

Fourth, regional differences in the perceived criminal liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 24 percent of the respondents from East China and 13.7 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal and medical professionals in East China tend to be more willing to hold the surgeon criminally liable compared to those in Central and West China.

Fifth, occupational differences in the perceived civil liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 60.7 percent of the legal professionals and 64.7 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.015; p

Sixth, regional differences in the perceived civil liability of the surgeon. According to the data, 60.8 percent of the respondents from East China and 62.3 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the surgeon liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.308; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 61.7 percent of legal and medical professionals from East China, Central, and West China, deemed the physician liable under the civil law.

D. Data Analysis for Question Four

1. Question Four and the Purpose of the Investigation. — Question Four: A chief physician formulated operational methods for routine medical treatments in her/his department. A resident physician in the department followed the methods in administering the treatment but also caused medical malpractice. The major cause of the malpractice was the methods, which are not consistent with generally-recognized and accepted medical practice. In your opinion, are the two physicians liable for medical malpractice? If yes, is it a civil or criminal liability?

First, the legal interpretation of the chief physician-resident physician relationship concerning their duties in the context of the vertical division of labor. Article 9(1) of the Hospital Working System and Job Responsibilities addresses the job responsibilities of medical practitioners in the following words: ‘The clinical chief physician of a department is responsible for directing the medical, teaching, research, technical training, and theoretical improvement work of the department under the leadership of the departmental head and guiding the medical work of attending and resident physicians in the department and conducting basic skill training in a planned manner.’

As stipulated in article 12(1), ‘a clinical resident physician is responsible for the medical treatment of a certain number of patients according to her/his working capability and length of experience under the leadership of the departmental head and the guidance of attending physicians. A newly graduated physician is required to be trained as a 24-hour resident physician for three years.’

Thus, a chief physician has the legal duty to supervise and guide the medical treatment performed by the resident physicians under her/him. If the chief physician fails to perform or does not earnestly perform her/his duty by personally supervising the resident physicians while they administer medical treatment, she/he shall be liable under relevant criminal and civil laws.

A resident physician can only administer medical treatments within her/his ability and she/he has to be instructed by a chief physician while doing so. If a resident physician can see that the medical treatment administered under the instructions of a chief physician is inconsistent with generally accepted medical practice, then, the resident physician has to report her/his opinions to the chief physician. If the resident physician has realized this inconsistency but has not reported it promptly, then there is legal causation between her/his act/omission and the infringement of the patient’s legitimate interests. Thus, objective imputation applies here, and the resident physician cannot claim her/his reliance on the chief physician to preclude objective imputation. In other words, the resident physician’s act/omission constitutes activity-adoption negligence. On the contrary, if the resident physician performs the medical treatment instructed by the chief physician, but is not capable of predicting and preventing the consequent harm, her/his act/omission does not constitute criminal negligence of infringing upon the patient’s legitimate interests. However, irrespective of the scenario, the resident physician’s act/omission has resulted in the infringement of legitimate interests. Thus, the resident physician is liable under the civil law according to the Tort Law.

Second, the purpose of investigation. A chief physician is supposed to have a greater degree of expertise and greater duty of care compared to other physicians; she/he should prevent the infringement of patients’ legitimate interests to the best of her/his ability. In contrast, a resident physician is supposed to have a relatively lower degree of expertise and a correspondingly more limited duty of care. In the scenario presented in Question Four, the duty of care that the resident physician is expected to fulfill is inconsistent with her/his ability of care, so jurisprudentially, it is not reasonable to hold her/him legally liable, especially criminally liable. However, theoretically, a resident physician’s ability of care should be defined according to the medical level at a given time and place or should be defined according to the medical expertise of the average resident physician at a given time and place. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the different definitions of the ability to provide care using statistical data analysis.

2. Data Analysis. — First, occupational differences in the perceived legal liability of the resident physician. According to the data, 75.4 percent of the legal professionals and 68.3 percent of the medical professionals deemed the resident physician legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal professionals tend to be more willing to hold the physician legally liable compared to medical professionals.

Second, regional differences in the perceived legal liability of the resident physician. According to the data, 78.3 percent of the respondents from East China and 70.5 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the resident physician legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal and medical professionals in East China tend to be more willing to hold the surgeon legally liable compared to those in Central and West China.

Third, occupational differences in the perceived criminal liability of the resident physician. According to the data, 31.4 percent of the legal professionals and 16.9 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal professionals tend to be more willing to hold the physician liable under the criminal law compared to medical professionals.

Fourth, regional differences in the perceived criminal liability of the resident physician. According to the data, 34.7 percent of the respondents from East China and 22.9 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal and medical workers in East China tend to be more willing to hold the resident physician liable under the criminal law compared to those in Central and West China.

Fifth, occupational differences in the perceived civil liability of the resident physician. According to the data, 63.8 percent of the legal professionals and 64.2 percent of the medical professionals deemed the physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.803; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 93.7 percent of the legal and medical professionals, whether in East, Central, or West China, deemed the physician criminally liable.

Sixth, regional differences in the perceived civil liability of the resident physician. According to the data, 68.1 percent of the respondents from East China and 61.1 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal and medical workers in East China tend to be more willing to hold the resident physician liable under civil law compared to those in Central and West China.

Seventh, occupational differences in the perceived legal liability of the chief physician. According to the data, 79.6 percent of the legal professionals and 79.8 percent of the medical professionals deemed the chief physician legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference in the opinion of the physician’s civil liability was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.909; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 79.6 percent of the legal and medical professionals, whether from East, Central, or West China, deemed the chief physician legally liable.

Eighth, regional differences in the perceived legal liability of the chief physician. According to the data, 78.5 percent of the respondents from East China and 80.4 percent of those from Central and West China deemed the surgeon legally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.118; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 79.6 percent of the legal and medical professionals in East, Central, and West China deemed the chief physician legally liable.

Ninth, occupational differences in the perceived criminal liability of the chief physician. According to the data, 34.6 percent of the legal professionals and 24.9 percent of the medical professionals deemed the chief physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.000). Thus, legal professionals tend to be more willing to hold the chief physician criminally liable compared to medical professionals.

Tenth, regional differences in the perceived criminal liability of the chief physician. According to the data, 34.1 percent of the respondents from East China and 30.8 percent of the respondents from Central and West China deemed the physician criminally liable. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.019; p

Eleventh, occupational differences in the perceived civil liability of the chief physician. According to the data, 64.3 percent of the legal professionals and 69.9 percent of the medical professionals deemed the chief physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the occupational difference was statistically significant (χ2=0.001; p

Twelfth, regional differences in the perceived civil liability of the chief physician. According to the data, 66.5 percent of the respondents from East China and 65.3 percent of the respondents from Central and West China deemed the chief physician liable under the civil law. A chi-square test confirmed that the regional difference was statistically non-significant (χ2=0.426; p>0.05). Thus, approximately 61.7 percent of legal and medical professionals from East, Central, and West China deemed the physician liable under the civil law.

IV. SUMMARY OF DATA ANALYSIS

The data show that either legal practice in China is discrete when it comes to the application of the principle of reliance to medical malpractice or that it is impossible to directly apply the principle of reliance to the analysis and judgment of individual cases. It can be inferred that China has a long way to go before it recognizes the applicability of the principle of reliance to medical negligence cases.

This survey deepened the scholarly understanding of the different concepts, methods, and attitudes adopted by legal and medical practitioners in responding to medical negligence. Thus, this survey provides data, practical criteria, and theoretical input for future research on the applicability of the principle of reliance to medical negligence cases.