STUDY ON CHINA’S LENDING INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL: FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF HISTORICAL CHANGE OF THE COMMON LAW

Zhao Haicheng & Song Yang

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. THE ORIGIN AND DECLINE OF RELIGION AND MORALITY-BASED INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL IN THE COMMON LAW COUNTRIES BEFORE THE 21ST CENTURY

A. The Origin of Anti-usury Law: The Legal Response of Religion and Morality

B. The Decline of Interest Rate Ceiling Control in Britain and America from the 18th to 20th Century

III. RECONSTRUCTION OF THE LEGITIMACY OF REGULATION ON THE ANGLO-AMERICAN INTEREST RATE BY BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

A. Underestimation of Borrowing: Human Beings Have Difficulties Overcoming Their Excessive Presupposition of Future Repayment Ability When Borrowing

B. Information Disadvantage: The Lender Will Use Its Information Advantages in the Process of Contract Negotiation and Execution

IV. LEGISLATIONS OF ANGLO-AMERICAN INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL WITH FINANCIAL CONSUMPTION PROTECTION AS THE CORE

A. Re-establishment of Interest Rate Regulation in the Legislations of Financial Consumer Protection at All Levels

B. Entitle Judges to Adjust Interest Rate Ceiling in Case

C. Application of Civil Forfeiture Procedure

D. Predatory Loan and Penalty Interference

E. Coordination of the Financial Consumer Protection System to the Interest Rate Ceiling Control

V. THE PATH OF LEGISLATIVE REFINEMENT ON CHINA’S INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL

A. Understanding of Legitimacy of Regulation

B. Separation of Institutions on Legislation and Enforcement of the Interest Rate Regulations

C. Breakthrough of the Single Standard of the Interest Rate Ceiling: A Classification of Business and Consumption Loan

D. Increased Flexibility of Interest Rate Rules: Expanding Judicial Discretion in Individual Cases

E. Filling in the Gap of Liability: Introducing an Independent Forfeiture for Unconscionability

The interest rate ceiling control has always been a predicament that puzzles the legislation and judiciary system in China and other countries. There is the infrequency of reversal between civil law system and common law system: the former authorizes judges to subjectively determine whether the interest rate stipulated in the contract is suitable or not, but the latter has always relied on written legislation to set the interest rate ceiling. Religion and morality-based Anglo-American law interest rate ceiling control once broke down at the end of the 20th Century, but behavioral economics has re-founded a new justified basis for ‘financial consumer protection’ in the new century and led to legislation being changed. This historical change is quite similar to what happened in China, which can provide references for us. The interest rate ceiling legislation in China should take the financial consumer protection as its core goal, and separate the institutions on legislation and enforcement of interest rate regulations, then gradually form a different control system of business loan and consumption loan, give judges discretion on interest rate adjustment in case, fill in the gap between civil and criminal liability by independent forfeiture procedures.

I. INTRODUCTION

As the core issue of informal finance, the regulation of the lending rate ceiling has always been a predicament in China’s legislation and the judiciary. There were two research peaks in 2012 and 2015. In general, the existing literature in China mainly follows the two approaches to ‘interaction of domestic theory and practice’ and ‘horizontal comparison of other countries’. The former is mostly based on the results of the law’s implementation in practice. It reviews the rationality of the regulation itself and its methodological merits and demerits. The latter mainly observes foreign legislative experience and amends the existing domestic rules by legal transplantation. The limitation of the first approach is that China’s existing regulatory legislation is only less than 30 years; the dispute between right and wrong has not gone through the test of time. The second approach tends to focus on the practice of the intended transplant country, pay less attention to the background of the legal exporting country.

This article attempts to integrate the above two approaches, to investigate the experiences of other countries through vertical historical extension, to extract the principles of changes through their histories, and to provide references for China’s legislation. There are three reasons why the common law system is chosen as the analog of comparative study: first, there is a rather infrequency of reversal in the interest rate regulation. Civil law systems often rely on judges’ discretion to determine whether the interest rate in the contract is appropriate. Instead, common law systems provide written regulations when interest rate exceeds a certain percentage, it could constitute being illegal. That is a complete legislative product.’ The path of a numerical ceiling control system in China is more similar to the evolution of the common law system, which makes the latter have analogy value. Second, the V-shaped path of ‘building, declining and reshaping’ of the interest rate ceiling in the common law system has lasted for more than 500 years, which can fully show the evolution process of the focus of regulation from religious morality to financial consumer protection. It is helpful for us to discuss the rationality of rules from the perspective of macro history. Third, In the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Private Lending Cases of 2015 (hereinafter referred to as the 2015 Provisions) has abolished the limit of four times of the bank loan interest rate which was set 25 years ago as legal standard for the private loan interest rate, and has re-established the ‘two-line, three-zone’ rule. However, the rule has the following doubts: whether the interest rate has to have relied only on the ex-post and passive judicial adjustment? Is it necessary to separate institutions on legislation and enforcement of the interest rate regulations? Can the sole numerical interest rate standards be adjusted to multiple rules for different industries and borrowers? Should judges have the discretion in case? How to expand the boundaries of illegal liability to optimize regulatory effects? The interest rate ceiling regulations in the UK and the US have a profound accumulation in both theories and cases, which can be used for references to answer the above questions in current China.

The structure of this article is as follows: The second part reviews the process and reasons for the gradually-declined regulation on interest rate ceiling based on the legitimacy of religion and morality from the 16th Century to the 20th Century in common law system; the third part analyzes how to reshape the legitimate basis of the interest rate ceiling control through the behavioral economics theory in the 21st Century; the fourth part examines the legislative experience of interest rate ceiling control focusing on financial consumer protection in modern common law system; the fifth part discusses the path of legislative refinement on China’s interest rate ceiling control.

II. THE ORIGIN AND DECLINE OF RELIGION AND MORALITY-BASED INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL IN THE COMMON LAW COUNTRIES BEFORE THE 21ST CENTURY

A. The Origin of Anti-usury Law: The Legal Response of Religion and Morality

Religion and morality formed the two major foundations of the early Anglo-American interest rate ceiling laws. ‘Regulation is a systematic reflection of public awareness of the moral evaluation of lending behavior.’The logic of the Christian doctrine’s initial prohibition on interest rates was that usurers sold time, and time could only belong to God. Usury was considered to be ‘anti-natural gains something for nothing’. For example, Aquinas pointed out that money was infertile, and using money to make money was a violation of the laws of nature.

As late as the 15th Century, these ideas began to change. The earliest question came from Dante: ‘Please go back to the point that usury hurts God’s favor, and untie the buck to me.’ From a macro-history perspective, the reason why anti-usury laws in the 16th Century that ‘allowed but limited a certain percentage of the interest rate ceiling’ to appear in Europe was the historical product of religious theology’s gradual concession to commercial loan interest. A typical example was between 1542 and 1713, due to the different religious attitudes of king or queen, the interest rate ceiling has fluctuated from 10 percent, 0 percent, 8 percent, and 6 percent to 5 percent.

Another cornerstone of early anti-usury laws was the puritan morality: even though commercial interest is a normal and legitimate part of the market, personal debt consumption was still generally considered shameful. In the early days of British and American society, the puritanical uppertendom all agreed to save money to become rich. According to Adam Smith: ‘(Loan consumption) has taken away the funds of the hardworking class to maintain the lazy class ... those who borrow money to splurge will not survive for a long time.’ Washington also stated: ‘If lenders do not consider the source of repayment, then borrowing is one of the most terrible things in the world ... especially when debt rolls up like snowballs.’

B. The Decline of Interest Rate Ceiling Control in Britain and America from the 18th to 20th Century

In the late 18th Century, the private industry’s thirst for capital had led to the rise of commercial borrowing. Industrial revolution and urbanization had lifted the middle class’s dependence on the seasonal income of agricultural society, and consumer finance had quietly emerged. On the one hand, liberals began to argue that interest rate ceiling harmed the personal freedom: ‘Compared to mature businessmen, the interest rate control that is fragilely attached to government paternalism is just a moral substitute.’ Mercantilists, on the other hand, began to blame the interest rate caps for capital outflows, leading ‘capitals flow to the place where the law smiles on them and never return.’ Under the double shock of liberalism and mercantilism, European countries canceled the upper limit of the legal interest rate. Britain in 1854 had completely abolished the statute of 1713 on the 5 percent ceiling. Denmark (1855), Spain (1856), Norway (1857), Sweden (1864), Belgium (1865), and northern Germany (1867) all abolished their national interest rate ceilings.

The US joined this trend. The weakening of control was firstly manifested in the establishment of the principle of excluding corporations in business-oriented lending. In 1850, the New York Dry Dock Bank borrowed 200,000 US dollars from Life Trust at an interest rate of 11 percent, which exceeded the 6 percent legal limit of the State of New York. The Court of Appeal ruled that the transaction was illegal and the creditor was sentenced to the penalty of principal plus interest. This judgment had triggered a public outcry, calling ‘it was a scandal which banks deliberately got rid of their debts.’ In view of the negative effect of the interest rate ceiling in this case, New York State first established the principle of exclusion of corporate, that is, inter-company lending was not subject to the interest rate ceiling control, and any agreement on interest rate between corporate was legal. Immediately after, 19 states in the US successively established the principle of corporate legal exclusion, which meant that the interest rate ceiling control fell invalid in business lending.

The collapse of the regulation of consumption lending interest rate ceiling originated from the Russell Sage Foundation small loan law. In the early 20th Century, Arthur Hamm and others pointed out that the traditional usury ceiling needed to be raised gradually so that the financial institutions could lend small loans to the working class on the premise of profitability. With the sponsorship of the Russell Sage Foundation, they drafted a model law requiring lenders of consumption loans to obtain government licenses. In exchange, the law eased the original interest rate limit and allowed licensed lenders to earn interest at an annual rate of 24 percent to 42 percent. Most states adopted this model law in the 20th Century, which had made it turning into the Uniform Small Loan Act.

The loosening of interest rate ceiling control in the US peaked at the end of the 20th Century. First, states tended to weaken or even abandon regulation. In 1965, every state in the US restricted the annual interest rate of borrowing, when it came to 2007, at least seven states in the US completely deregulated, and 35 states allowed payday loans to charge more than 300 percent of annual interest. Second, the interest rate regulations in different states were polarized. For example, New York State has limited annual interest to no more than 25 percent, resulting in payday loans almost disappearing in the state. But Missouri has allowed payday lenders to charge 75 percent of the fee, resulting in a maximum annual interest rate of 1955.36 percent. Third, the terms of the usury laws in early times were simple and straightforward, and they were directly specified at the Annual Maximum Rate, which can be easily compared with each other. The expression nowadays used by states for the upper limit is too complex to compare. Peterson summarized this phenomenon with ‘salience distortion’, ‘(even) the value of the usury limit has not changed much from state to state, and its internal meaning has been very different.’ A reflection of the collapse of regulation was the rapid development of ‘payday loans’, which originated in 1993. Lenders provided small short-term unsecured loans, and borrowers repaid on paydays. The loan amount was generally between 100 US dollars and 1,500 US dollars, and the interest rate reached about 300 percent. According to statistics from some scholars, as of 2005, there were about 23,000 to 25,000 payday loan operations in the US. Due to the high fees of payday loans, many customers were overdue and could only continue to borrow, result in paying multiple times of the principal interest to loan institutions, which was called ‘suicide trap’.

In general, from the 18th Century to the end of the 20th Century, Britain and the US faced a situation that the traditional religion and morality-based interest rate ceiling control collapsed because of commercial desire. Lending at a ‘catastrophic’ rate became ‘victimless crime’, which was regarded as an adult permitted private act between people.

III. RECONSTRUCTION OF THE LEGITIMACY OF REGULATION ON THE ANGLO-AMERICAN INTEREST RATE BY BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

As early as the 18th Century, economists began to question the rationality of individuals in lending. Although Adam Smith believed in market rationality, he still wrote with worry: ‘As an important part of human instinct, the over-weening conceit is an ancient monster that philosophers have always emphasized ... Overconfidence constitutes an important reason for anti-usury law.’ It was inconsistent with Bentham’s view of the unconditional autonomy of borrowing rates. On the one hand, Keynes, the originator of state interventionism, recognized the market’s regulation of interest rates: ‘the excess of capital will mean the ‘euthanasia’ of profit-taking people ... the wealth holder will eventually lose control of others.’ But he was also cautious to point out that there was an animal spirit in human behavior. The sense of urgency to take action was not only an important driving force for human progress but also a potential danger to humans.

Behavioral economics, which was founded at the turn of the century, denies that humans have constant rationality, but believes that it is possible to describe, predict, and even model human behaviors, thus opening up a new dimension in the study of law and human behavior. GA Akerlof and RJ Shiller pointed out in the book Animal Spirit that personal emotions drove the decisions that humans can make, and the source of the decisions was largely dependent on the human subconscious. The psychological vulnerability before making a decision cannot be ignored. This analysis poses a serious threat to the efficient market theory constituted by ‘smart market participants’. If the rationality of the participants in the consumer financial market cannot be proved, how can the law grant all borrowers the freedom of access to funds? In the past ten years, many legal and economic literature has analyzed in-depth why humans have fallen into an irrational situation in the measurement of lending interest rates. Among them, ‘underestimation of borrowing’ and ‘information disadvantage’ are considered to be the two major reasons that cause lenders to lose their rationality.

A. Underestimation of Borrowing: Human Beings Have Difficulties Overcoming Their Excessive Presupposition of Future Repayment Ability When Borrowing

1. Self-serving Bias. — Human borrowers of all ages will underestimate the economic impact of death, old age and illness due to their psychological resistance. ‘Almost everyone is convinced that they are different from others in the face of misfortunes.’ The instinct of humans who tends to the self-shield crisis has greatly interfered with its ability to weigh borrowing. Dulkin pointed out that almost all credit cardholders were convinced: ‘Maybe others cannot afford it, but I can solve the problem of high-interest rates on credit cards.’

2. Hyperbolic Discounting. — Human beings are apt to care about immediate interests and ignore long-term planning, which will cause them to underestimate the long-term impact of interest rates. But the natural breeding of debt is slowly generated through the accumulation of time. This requires borrowers to have high self-control capabilities, and those who tend to borrow and consume in advance are precisely those with poor self-control.

3. External Dilemma. — Under the influence of emotions, financial consumer borrowers often choose to accept the solution with the least difficulty in understanding when they face their economic pressure, rather than weighing the pros and cons. Human energy and capacity are limited. In many cases, consumers tend to accept borrowing solutions that can solve their difficulties immediately, and most of their attention focuses on how to get out of trouble quickly. The lack of energy and capacity makes it difficult for them to take risks into account that high-interest rates may bring in the future.

4. Willingness to Pay. — Research shows that the feelings of the loss of pleasure are twice as much as the loss. In other words, when facing loss, the vast majority of people will cherish what they already have, leading to an irrational confrontation of the loss. Once consumer borrowers take ownership of a vehicle or house through an overdraft, they are likely to accept high interest without reason just because of fear of loss. According to Peterson statistics, the expenditure on mortgage car consumption even exceeds 140 percent of the car value itself.

B. Information Disadvantage: The Lender Will Use Its Information Advantages in the Process of Contract Negotiation and Execution

1. Information Overload. — When consumers face too much information comparisons and choices, they tend to simplify them and only consider the minimum factors. In other words, when consumers’ knowledge and understanding ability is difficult to cope with the complexity of financial products, the cost of information identification and comparison makes it easy to ignore the most important interest rate factors. Peterson pointed out that when lenders incorporate a large portion of interest rates into complex liquidated damage calculation formulas, few consumers can digest the lengthy contract terms and formulas and truly understand the abnormally high-interest rates behind them. Legislation must consider the cost of obtaining information for a consumer lender and its ability to deal with that information.

2. Confirmation Bias. — Humans look for evidence in support of their opinions, and interpret ambiguous information toward their positions rather than rationally evaluate it. Therefore, the weak borrower is easy to be hypnotized by language, expression, and even technology. For example, the 15 percent monthly interest sounds much more acceptable than the 391 percent annual interest rate, but in fact, there is no mathematical difference between the two.

3. Anchoring Bias. — Consumers rely heavily on first impressions when analyzing risk and return, and this leads to their lack of further analysis of subsequent continuous information. Lenders who are familiar with the anchoring bias often put the terms that are in the consumer’s favor on the first page of the contract, and list the unfavorable details in the appendix.

4. Debt Cycle. — Usury products will lead to consumers’ psychological dependence and fall into a vicious circle of debt. Lenders often deliberately encourage consumers to increase the number of deferred repayments, taking the opportunity to charge interest when the principal has not been repaid. The US Consumer Protection Commission cited an extreme case: A woman was charged up to 1,000 US dollars for delaying the payback of a payday loan of only 150 US dollars over a period of six months.

IV. LEGISLATIONS OF ANGLO-AMERICAN INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL WITH FINANCIAL CONSUMPTION PROTECTION AS THE CORE

‘If the foundation of the law disappears, the law will disappear.’ Through behavioral economics, Britain and the US and other common law countries have repositioned the legitimacy of interest rate ceiling control, and a new round of legislative practice has gradually shifted from pure anti-usury to small loan legislation, thereby embedding interest rate ceiling into the financial consumer rights protection system.

A. Re-establishment of Interest Rate Regulation in the Legislations of Financial Consumer Protection at All Levels

Considering the situation that consumer credit is rampant in military bases in the US, the US Congress at the federal level, limited the annual interest rate of consumer credit for military service personnel and their families to 36 percent in 2006. The amendments to the Truth In Lending Act and Payday Loan Reform Act of 2009 both try to restrict the payday loan interest rate, ‘no matter who the lender is, each dollar of the payday loan can only charge interest and related fees of no more than 15 cents.’

At the state legislative level, the non-consumption interest rate in Colorado can be as high as 45 percent, while the ceiling for consumer interest rates is as low as 12 percent. North Carolina announced in 2005 that it would repeal its law on exempting short-term small loans from interest rate caps. New Hampshire (2011) and Oregon (2010) have restored the caps of 36 percent, Georgia (2011) has reset the caps to 10 percent, and Columbia (2011) has restored the statutory caps of 24 percent. The Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that legislation exempting small loans from interest rate caps is unconstitutional in 2008.

B. Entitle Judges to Adjust Interest Rate Ceiling in Case

Unlike German judges who judge whether the agreed interest rate is reasonable based on the principle of ‘profiteering act’ which can be traced back to the rule of ‘laesio enormis’ in roman law, American judges generally strictly follow the upper limit of interest rates determined by the legislators, and rarely actively adjust. The judge in Universal Credit Co. v. Lowell pointed out: ‘Even if the (statutory) punishment is too severe or even unnecessary, it is a legislative issue and the court must comply with these rules.’ It may partly because the US has a requirement of applying unconscionability, which needs both the subjective (procedural) and objective (substantive) standards, and that makes judges more cautious in using this rule.

In recent years, the Anglo-American legal system has learned from Germany’s practice in order to weaken the rigidity of legislation. First of all, the amendment of the Money Lenders Act of 1927 in Britain adopted a subjective and objective composite standard: (1) Borrowings with an annual interest rate of more than 48 percent will be initially identified as unconscionable; (2) But lenders are allowed to provide evidence to prove the interested legitimacy; (3) If the judge determines that the annual interest rate is too high, the contract interest rate can be adjusted to a fair level at his discretion. Affected by the above act, the legislations of some states in the US (such as New Mexico) have also begun to use the method of judicial discretion. Another approach is to increase the burden of proof on the borrower. In New York State, where the interest rate ceiling is the strictest (25 percent), the judge in the Frick Co .v. Tuten case stated that: ‘Due to the harshness of the New York usury laws, the defense is not favored, and in case of doubt a rather heavy burden of proof is thrown upon the person asserting that a bargain is usurious ... Courts can, of course, increase the borrower’s burden of proof.’

C. Application of Civil Forfeiture Procedure

Considering the gap between the invalidity of civil contracts and penalties for usury, the federal and many states’ laws of the US provide that when the property is used in a way that is prohibited by law, property ownership passes to the government. This civil forfeiture has been widely cited by courts to fill the aforementioned legislative gaps. The state regulations on the amount of forfeiture vary greatly: (1) or equivalent to double (Oklahoma) or triple (Idaho) the contract agreed interest when interest rate exceeds the legal limit; (2) or a certain multiple of contract amount, double (Alaska) or triple (Utah); (3) or a certain percentage of the principal of the contract (Iowa 25 percent of the principal); (4) or the principal plus a fixed amount (2000 USD, Wisconsin).

As the Hull v. Augustine verdict stated, ‘Our statute of usury is highly penal.’ The civil forfeiture provides a modest and refined means to fill the regulatory gap: first, not all loans exceeding the upper limit of interest rate are subject to forfeiture, and only those exceeding a certain proportion (for example, 125 percent in Florida or 120 percent in Mississippi) of the upper limit are subject to this procedure; second, the standard of evidence only needs to reach superior evidence, rather than ‘beyond reasonable doubt’; the third is to ensure that the forfeiture is based on the public interest, and to avoid the borrower who also participates in the illegal behavior from obtaining the undeserved windfall, some states directly mandate that confiscated property must be used for public purposes, such as Iowa, which requires the fine to be paid to the treasurer of state for deposit in the general fund of the state.

D. Predatory Loan and Penalty Interference

At least eleven federal regulators have identified the term ‘predatory’ in the US as ‘prone to harm or exploit others for personal gain or profit’. It is generally believed that an annual interest rate of more than 45 percent stipulated in the contract has a clear ‘illegal and exploitative’ intention and is necessitated a penalty. Some states have more stringent regulations. New York states that an annual interest rate of more than 25 percent constitutes a criminal offense and is punishable by five years’ imprisonment or a fine of 5,000 US dollars, or both. Vermont imposes six months in prison or a fine of 500 US dollars (or a combination of both) for the first intentional violation of the usury law and doubles the penalty for the second violation. Meanwhile, Canada and Hong Kong both criminalize lending practices with annual interest rates above 60 percent.

E. Coordination of the Financial Consumer Protection System to the Interest Rate Ceiling Control

The financial consumer protection system has provided supporting measures for interest rate ceiling control, which has been a major feature of legislation in recent years. One is to start with standardized information disclosure, requiring credit institutions to provide comparable interest rate information. For example, Massachusetts requires interest rates on consumer credit transactions to be made public in a unified manner. The second is to allow interest rate liberalization as a condition requiring lenders to apply for market access permit registration to achieve a variety of regulatory objectives such as business area restriction, disclosure requirements, etc. Corresponding to relax the interest rate on consumer credit to 75 percent in the state of Missouri, each city is strictly restricted to have no more than three consumer credit outlets. West Gap, Utah, stipulated in 2011 that there should be no more than one consumer credit outlet for every 10,000 population. Another approach is to restrict its geographic location. For example, California bans the establishment of consumer credit outlets within 500 feet of schools, and West Canyon, Utah, in 2011 stipulated a minimum distance of 600 feet between consumer credit outlets.

V. THE PATH OF LEGISLATIVE REFINEMENT ON CHINA’S INTEREST RATE CEILING CONTROL

The change in Anglo-American interest rate ceiling control perfectly interprets what Selznick said about the ‘responsive law’: changes in the macro-level of society have led to the reinvention of legislative ideas, and then review the system itself, which has made it change from a single judicial standard to a more precise governance in responding to the diverse needs of society. The Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China also mentioned the goal of constructing the legal system is to ‘focus on the target of legislation and advance the refinement of legislation.’ From this point of view, China’s legislation in the future should respond to the social requirements of informal finance for interest diversification and complexity. Historical enlightenment from the Anglo-American law system can provide inspirations to answer the following questions in China: first, what is the basis of the legitimacy of interest rate ceiling control nowadays? Second, is it necessary to separate institutions on legislation and enforcement of the interest rate regulations? Third, can sole numerical interest rate standards be adjusted to multiple rules for different industries and borrowers? Fourth, is there any room for judges to adjust in individual cases? Fifth, how to expand the boundaries of illegal liability to optimize regulatory effects? This chapter will discuss the above issues based on China’s circumstances.

A. Understanding of Legitimacy of Regulation

The legitimacy and rationality of the interest rate cap control are highly controversial, and the Chinese academics have not reached a consensus. A large number of economists have denied the rationality of the regulation. Some legal scholars also believe that ‘the market should determine the interest rate on loans.’ Even scholars who agree with the regulation have different reasons. Some believe that ‘prevention of risks’ is predominant, while others think that we should ‘prevent the Matthew effect of usury’.

In practice, the Supreme People’s Court also has two voices, either based on ‘financial order’ or from ‘optimized allocation of funds in financial markets.’ The Notice by the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Ministry of Justice of Issuing the Opinions on Several Issues concerning Handling Illegal Lending Criminal Cases issued in October 2019 (hereinafter referred to as 2019 Opinions) emphasized that the legitimacy of interest rate ceiling is for ‘effectively safeguarding the national financial market order, as well as social harmony and stability.’

The author believes that the legitimacy of interest rate control has the characteristics of the times, and the protection of financial consumers should be the cornerstone of the establishment of interest rate ceiling control in the 21st Century.’ There is only one prerequisite for the development of loan control in current times, that is, the extreme imbalance between the two parties in the transaction has given reasons for legal intervention, which will defend consumers from a shark of loan.’ Under the background that the traditional negative moral evaluation of interest income is gradually weakening and the industrial and commercial civilization needs capital expansion, the legitimacy of China’s modern interest rate ceiling control should be based on the protection of weak borrowers and thus maintain the stability of financial order. The lending market is different from the general pricing market system, and the borrower is not a ‘rational person’ in the assumption of traditional civil law. It is impractical to give the freedom of interest rate negotiation to the lenders and borrowers, ‘Rather than making a case for a free market in loans, Adam Smith made a case for limiting interest rates at something a bit above the lowest market rate.’ The law’s control of excessively high-interest rates is essentially an amendment to the principle of party autonomy in traditional contract law. This amendment may be through civil law principles such as the profiteering act; it may also be through controlled by numerical interest rates which are to be done by the Anglo-American law system.

B. Separation of Institutions on Legislation and Enforcement of the Interest Rate Regulations

From the experience of the common law system, the power of making an interest rate ceiling belongs to the legislative system. After amending the provision of Several Opinions of the Supreme People’s Court on Handling Lending Cases in 1991 and abolishing the regulation of lending interest rate shall not exceed the four-time upper limit of bank loan interest rates, the 2015 Provisions still insist on the practice of combining the power of legislation and the power of enforcement by the judiciary, that is, the Supreme People’s Court itself determines the upper limit of the legal interest rate. At the same time, it depends on the judge’s decision on individual trials to implement this provision. This practice is likely to be the result of the path dependence of the judicial dominated private lending rate control over the last 30 years.

However, considering the information cost of finding and reviewing illegal acts, it is natural that the enforcement power should be attributed to the judicial institution, but the power of interest rate ceiling legislation should return to the financial supervision institution itself. First, determining the upper limit of the legal interest rate has exceeded the legal boundary of judicial power. Interest rates should have the dual attributes of private contract law and financial consumer protection. The latter is one of the important components in the ‘twin-peak model’ of financial regulation and supervision. The focus of future interest rate regulation should be shifted to the financial regulation and supervision institution. Second, due to the ex-post and passive nature of the judiciary, with the limitation of the perspective of individual trials, it is difficult for the judiciary to fully measure the motivations of market entities and the macro changes in society, and to adjust the interest rate ceiling timely. Here is one obvious evidence that the ‘four-time upper limit of bank loan interest rates’ regulation in 1991, which was legislated by the judiciary has been in existence for over twenty years without any correction. Third, the judiciary does not have the professional capabilities of financial supervision. The determination of this upper limit in the future requires the use of big data of informal financial interest rates, for example, the People’s Bank of China has established informal financial inspection points in Wenzhou city and other places, ‘the financial supervision institutions are very professional and has more flexible access to information than the courts’. Fourth, a single interest rate ceiling control is easy to evade and cannot bear the burden of financial consumer protection alone. The law needs to complete the embeddedness of interest rate ceiling control on the legal system of financial consumer protection, and even need to lose a certain of the ceiling control for obtaining the cooperation of regulated parties in market access registration, information disclosure, regional restrictions, loan contract standardization, and other aspects. Obviously, this task cannot be completed by the judiciary.

For the above reasons, the power to determine the legal interest rate should be attributed to the legislative or administrative institutions. In addition to common law countries, interest rates in Belgium and the Netherlands are also adjusted by the legislators every six months according to market conditions. The Legislative Council of the Hong Kong has also instructed the Financial Services and Treasury Bureau to ‘provide prosecution figures for loan interest rates exceeding the legal limit set by the Money Lenders Ordinance for each of the past five years, and regularly review whether the limit is in line with Hong Kong’s economic, cultural and social conditions, and test the effectiveness of anti-usury regulation.’

Therefore, it is necessary to separate the institutions of legislation and enforcement of the interest rate regulation from the Top-level Design. This can also be proved by opinions within the Supreme People’s Court that: ‘the competent authority of legislating interest rate, namely the People’s Bank of China, must make a reasonable and clear decision according to the law based on comprehensively measuring the advantages and disadvantages of interest rate ceiling control.’ Considering the current situation of China’s financial multi supervision, it can be considered that the department responsible for financial consumer protection in the People’s Bank of China should set the interest rate ceiling, and the People’s Congress should regularly question and review the rationality of the upper limit value of interest rate. On the premise that the court retains the enforce power, the regulatory and judicial departments can establish a joint session in order to timely share the information and understand the social effects of the regulations.

C. Breakthrough of the Single Standard of the Interest Rate Ceiling: A Classification of Business and Consumption Loan

Due to the legitimacy of setting the interest rate ceiling has changed, it will inevitably lead to the refined classification of business lending and consumption lending. The former follows commercial autonomy; the latter is based on public law to protect the vulnerable groups. That means the amount of loan, usage, type, and lender roles may have a legislative impact on the interest rate ceiling control. Many scholars have pointed out that legislation should distinguish between consumption and business lending for interest rates ceiling control in China. But the Supreme People’s Court of China still adheres to the non-discriminatory control standards at present, on the grounds that it is unrealistic to distinguish the two in China at present, ‘the current development of Chinese market is not complete, and consumer lending and business lending are difficult to judge in judicial practice ... (Differentiation) will cause difficulties in the implementation of interest rate control policies and judicial review.’

The author noticed that refined legislation must have its information cost and enforcement cost. But in the long run, the classification of consumption lending and business lending is becoming increasingly apparent and imperative. Even in Germany, where judges’ subjective judgments are predominate, once the consumer credit exceeds 30 percent, it is considered to meet the objective conditions of windfall profits; while the commercial lending is much looser, and even the annual interest rate of 180 percent is not considered to constitute a violation of public order and fine customs or windfall profits. In the future, China can gradually import references from the ‘principle of excluding corporations’ of the US and relax the control of business lending interest rate step by step. However, it should be noted that China does not yet have the conditions to abandon the interest rate ceiling on business loans completely. On this issue, we cannot copy and paste the experiences of the Anglo-American law system. It is necessary to adhere to the existing red line of 36 percent and 24 percent for a certain period of time.

On the other hand, interest rate disorder has appeared in the field of specific financial consumer groups and caused social problems such as the ‘naked loan’ phenomenon. In April 2016, the Ministry of Education, together with the general office of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, issued the Notice on Strengthening the Risk Prevention and Education Guidance of Campus Network Lending, which pointed out that: ‘... Some Internet platforms have published false advertisements, lowered the loan threshold and concealed actual charges standards, to induce students to overspend and even fall into the usury trap. They have infringed on the rights and interests of students.’ China does not yet have a personal bankruptcy law. Disorders in consumption lending may result in disaster on society. Therefore, it is necessary to refer to the aforementioned 987(b) Act of the United States in 2006, and strictly set a far lower upper limit of consumption interest rate than 24 percent for consumption loans, especially for special loan borrowers such as soldiers and students.

D. Increased Flexibility of Interest Rate Rules: Expanding Judicial Discretion in Individual Cases

Another point of discussion on the refinement of legislation is: based on the need for flexibility of rules, can the legislation give judges the power to adjust interest rates at their discretion in case? Checking the meaning of article 26 of the 2015 Provisions, none of the judges can subjectively determine whether interest rates are too high or actively adjust interest rates. The reason is that the Supreme People’s Court believes that ‘objective unified line’ is more suitable to show the intention of government financial control to the public and the simple standard can overcome the deficiency of the professional financial knowledge of our judges.

Although the Supreme People’s Court’s position is somehow justifiable, there are at least three pitfalls in abandoning the ‘flexible standards’ by relying solely on the ‘bright line’: First, after all, borrowing is a transaction between private individuals, and each contract has its characteristic. Ignoring the specific situation of the case and cutting off the relationship between the interest rate and the contracting situation will hinder the realization of individual justice in the case. The author noticed that there is another voice within the Supreme People’s Court that ‘while uniformly setting interest rates, the people’s courts can also use the relevant regulations like unconscionability or exploitation of his unfavorable position by the other party to determine the scope of interest protection.’ Second, the integration of subjective and objective approaches is the trend of global interest rate adjustment, which cannot be missed. As mentioned before, the common law system introduced judges’ discretion in addition to interest rate cap legislation. France, the country of the civil law system, also has a similar approach. It has capped interest rates at 33 percent, but in recent years judges have been allowed to adjust them based on interest rates that refer to similar types of bank transactions. The Money Lenders Ordinance in Hong Kong presumes contracts with an annual interest rate between 48 percent and 60 percent as ‘unconscionability’, but also allows the court to subjectively determine whether the ‘unconscionability’ is established according to situations. If it constitutes unconscionability, the court can appropriately intervene to reduce the interest rate level. In other words, there is a trend of integration between the two legal systems on this issue. The consensus is that the numerical interest rate ceiling should only be the basis of judicial discretion, but not an absolute criterion. Third, the protection of financial consumption requires the cooperation of judicial discretion. If proper space is not left in the judicial discretion, it will be adverse to the improvement of the judges’ abilities, which may cause the disconnection between judicial and financial realities.

One realistic suggestion is that, based on the objective criteria determined by the legislative department, the judges are partly given the discretion to adjust the upper limit of interest rate in the case by imitating the precedent of liquidated damages adjustment. Meanwhile, the judge is required to explain the reasons for the adjustment. The judge’s power of interpretation can refer to the adjustment of the penalty for the breach of contract. On the other hand, in order to ensure that the discretion is not abused, the scope of case adjustment should not exceed a certain proportion of the legal limit (such as 20 percent), which can be gradually adjusted by the Supreme People’s Court from time to time according to the specific situation.

E. Filling in the Gap of Liability: Introducing an Independent Forfeiture for Unconscionability

At present, there is civil and criminal liability for the penalty when it exceeds the legal limit of interest rate in judicial and administrative regulations. On the one hand, the Supreme People’s Court has restricted its liability to the scope of civil liability carefully. ‘The common practice in limiting private interest rates by private law is to invalidate the interest rate agreement above the upper limit. Interest payments exceeding the upper limit should be returned to the debtor as unjust enrichment.’ This practice is difficult to reflect the punitive nature of illegal acts, and it also results in regulation inflexible. Even if a judge attempts to achieve that ‘the property thus acquired shall be turned over to the State or returned to the collective or the third party’ through article 59 of the Contract Law in China, the subjective criterion of ‘malicious collusion between the parties’ must be satisfied which is difficult for judges. On the other hand, the 2019 Opinions introduces criminal punishment measures. For example, article 1 stipulates: ‘Regularly granting loans to the members of society in general for profits, in violation of the provisions issued by the state … in such a manner as to disrupt the financial market order, shall, under serious circumstances, be punishable as the crime of illegal business according to the provisions of article 225(4) of the Criminal Law.’ At the same time, the actual annual interest rate of more than 36 percent is considered as one of the serious circumstances.

But the problem is that between civil liability and criminal liability, China’s punishment for pure ultra-high interest rate lending has a vacancy in the law. Although article 22 of the Measures for Banning Illegal Financial Institutions and Illegal Financial Business Activities of 2011 stipulates that the People’s Bank of China can ‘impose a fine of not less than the number of illegal gains but not more than five times the amount of illegal gains’ on illegal financial services. But the question is, as the supervision financial institution, the People’s Bank of China rarely determines the pure ultra-high interest rate lending behavior is ‘illegal financial service’ according to article 22.

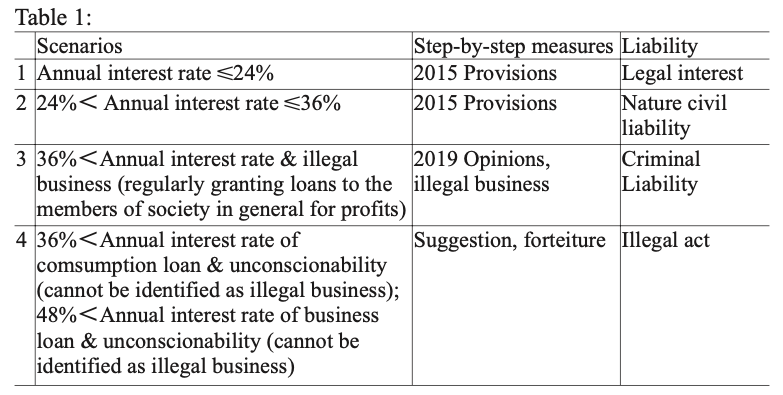

In this regard, the author proposes that China can distinguish between business and consumption loans, and define pure ultra-high interest rate lending behavior as ‘unconscionability’, thereby introduce the independent penalty system, and fill in the gap between civil liability and criminal liability, to form the stepped punitive deterrence. See Table 1 for details.

The advantage of this approach is that, for consumption lending with an annual interest rate of more than 36 percent and business lending with an annual interest rate of more than 48 percent, if the above two types of lending cannot be identified as usury-type businesses which should be subjected to criminal law, judges can define them as illegal acts of ‘unconscionability’. In addition to deciding that the portion of interest rate exceeding 24 percent or 36 percent is invalid, lenders will be punished with independent property punishment in the name of public interest. As for the amount of forfeiture, in order to maintain the consistency of current laws, it can be referred to the provisions of the Measures for Banning Illegal Financial Institutions and Illegal Financial Business Activities of 2011, that is, ‘confiscate the illegal gains and impose a fine of not less than the amount of illegal gains but not more than five times the amount of illegal gains; if there are no illegal gains, it shall impose a fine of not less than 100,000 yuan but not more than 500,000 yuan.’