THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHINA’S TAX TREATIES POLICY:TAKING THE TAX TREATIES REVISED AND SIGNED BY CHINA IN THE LAST DECADE AS THE SAMPLE

Qiu Dongmei

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. TREATY RESIDENT

III. PERMANENT ESTABLISHMENT

IV. INVESTMENT INCOME, ROYALTIES AND CAPITAL GAINS

A. Dividends

B. Interest

C. Royalties

D. Capital Gains

V. RELIEF OF DOUBLE TAXATION

VI. ANTI-AVOIDANCE RULES

A. Beneficial Ownership

B. Limitation of Benefits Clause, PPT Provision and Other Anti-avoidance Rules

VII. CONCLUSION

This paper argues that, the past ten years is an unprecedented golden decade for tax treaties policy in China to take shape. The rapid developments have been closely interwoven with the economic, legal and institutional reforms that have taken place within the country in the larger scale, and deeply affected by the dynamic changes in the global realm of international taxation. Based on the examination of several key provisions under 29 tax treaties China signed and revisited since 2008, this research aims to offer answers to a set of questions such as: what are the differences between the BTTs that China signed with the developed countries and the developing countries? To what extent may the China’s tax treaties network facilitate the outbound investment, particularly the one-belt-one road initiative? How will the signature of BEPS multilateral convention (2017) affect China’s existing bilateral tax treaties?

I. INTRODUCTION

The economy growth of China in the past four decades is astonishing, so is the expansion of its tax treaties network. Since the first bilateral tax treaty (BTT) concluded with Japan in 1983 to eliminate double taxation on income and capital, China today has boasted the third largest number of such treaties in the world. This network covers the BTTs with 107 countries and three tax agreements with Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan respectively. In general, China’s BTTs policies developed through three phases: treaties signed with the developed countries in the 1980s; treaties signed with BRICs, transition countries and many developing countries in the 1990s and the early 2000s; the continuous treaty expansion and the systematic revision of BTTs after 2008. This paper argues that, the past ten years is an unprecedented golden decade for tax treaties policy in China to take shape. Such rapid developments have been closely interwoven with the economic, legal and institutional reforms that have taken place within the country in the larger scale, and deeply affected by dynamic changes in the global realm of international taxation.

Taxes covered by the BTTs, in China’s context, refer to two types: enterprise income tax (EIT) and individual income tax (IIT). The past decade has witnessed the radical legislative reforms in both these two regimes. In January 2008, the unified Enterprise Income Tax Law (hereinafter referred to as the EITL) took effect, replacing the dual track system which granted more favorable income tax treatments to foreign invested companies and foreign enterprises, compared with their Chinese counterparts. When the playing field was levelled, the significance of BTTs began to surface, and stimulated the growing quest among foreign investors to seek benefits under China’s existing BTTs. Meanwhile, the EITL introduced a set of anti-avoidance rules to safeguard the national tax base, and treaty shopping phenomenon drew increasing attention from tax authorities. Anti-avoidance rules of different forms appeared in the BTTs. In the area of the IIT regime, the long-anticipated overhaul took place as the revised Individual Income Tax Law (hereinafter referred to as the IITL) was passed on August 31, 2018, taking effect from January 1, 2019. The revised IIT regime introduces the combined system to tax comprehensive and schedular income, redefines the resident individuals, adjusts tax brackets, allows the higher exemption threshold and the deduction of specified expenses, and moreover, introduces the anti-avoidance rule. The enhanced legislation, together with increasing transparency in the IIT tax administration and closer ties with other jurisdictions in tax information exchange, are expected to close potential loopholes for tax dodgers. Again, the importance of BTTs to eliminate double taxation emerge, both for Chinese resident individuals deriving foreign income and non-resident individuals receiving China-sourced income, whereas combating the abusive use of treaties by individuals will turn out to be a new focus for tax authorities.

Besides the legislative changes, the transformation of China’s economic status in the cross-border investment also exerted profound and visible impacts on its BTTs policy. The following chart shows that, in 2007, the volume of China’s FDI inflow (USD 83.5 billion) is more than three times the volume of the FDI outflow (USD 26.5 billion), ranking at 6 and 17 in the world. In the next few years, China’s outward investment gained a much stronger growth momentum, and surpassed the inbound FDI for the first time in 2016, making China a net capital exporter in that year. In 2018, the volume of China’s FDI inflow is USD 142 billion and the FDI outflow USD 129.8 billion, as the global ranking rose to number two and three respectively. An important driving force, behind this miraculous growth of the outward investment, is the roll-out of the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched by the government since 2013. With the continuous expansion of the BRI both in its geographic scope and investment volume, the government has been facing an imperative and pressing task to reconsider the BTTs policy to adapt to its strategic economic outreach.

Having the BTTs in place is one thing, and keeping them operational and properly implemented is another, as the latter is largely contingent upon the political, legal and institutional environment of a country, and is also closely interacted with the domestic tax rules. In China, the BTTs’ interpretation and implementation, de facto, rest upon the State Administration of Taxation (SAT), whereas the courts’ role in this regard is almost negligible. Since the SAT is subordinated to the State Council, the administrative rules the SAT pronounced have been heavily impacted or dictated by the State Council which maps out the national policy. For example, the governmental reform upheld by the State Council to streamline the administration and cut the red tape since 2013 have led to the simplified procedures for both residents and non-residents to apply for treaty benefits, as well as easing tax compliance burdens for non-residents that receive the China-sourced income; tax deferral rules for foreign reinvestment and more generous tax credit for outbound investors issued after 2017 are the repercussion of the State Council’s policy to stimulate foreign investment; furthermore, to echo the call of the State Council for a deeper commitment to govern according to the law since 2013, tax regulatory documents issued by the SAT are much standardized in the format with more transparency in the rules formulation. As tax officials have grown in both their knowledge and experience in tackling the tax treaty-related matters, taxpayers have also gained increasing awareness to take use of BTTs. Take the mutual agreement procedure (MAP) as the example, statistic shows that in 2008, the opening inventory of MAP cases in China is only one, and at the end of 2017 the number of pending MAP cases has grown to 131.

Nonetheless, China is not alone in restructuring its BTT policy. In the international tax regime, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the G20 spearheaded a sweeping reform across the globe under the banner of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Actions Plan in 2013. This movement represents a collective action of more than a hundred jurisdictions to combat the BEPS exploited by multinational enterprises to avoid taxes by the aggressive tax planning. Among the fifteen BEPS actions, four are related to tax treaties. To implement these tax treaty-related measures produced in the BEPS actions in a swift, coordinated and consistent manner across the network of existing tax treaties without the need to bilaterally renegotiate each such treaty, the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent BEPS (hereinafter referred to as the MLI) was released in July 2017 with 67 jurisdictions as the first signatories. The general aim of the MLI is to enhance the source-based taxation, ensure the single taxation and limit treaty shopping. To achieve this goal, the MLI interacts with the existing BTTs in a highly innovative way: the signatories of the MLI are given considerable discretion to designate covered tax agreements (CTAs) to which the MLI will apply; a variety of solutions are provided for signatories to implement the MLI by opting in or opting out certain provisions and implementing the minimum standard in multiple alternative ways. The relevant provisions in the MLI provisions may amend, substitute or supplement the already existing BTTs only if the options made by two signatories match. In this sense, the MLI is designed to apply alongside with the BTTs. Up to April 9, 2019, the MLI has 87 signatories, among which 25 have ratified the MLI.

The SAT officials have been playing a key role in the formulation of this global multilateral instrument. In July 2017, China (also representing Hong Kong) joined the MLI as the first batch of the signatories, and the ratification process is still ongoing at domestic. According to the provisional position the SAT submitted to the depository of the convention in 2017, China chose 102 tax treaties as the CTAs, excluding treaties with Chile and India as well as tax arrangements with Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. The wide coverage of the countries list matches with the options made by nearly 60 jurisdictions which also designate the BTTs with China as the CTAs. As a member of the BEPS inclusive Framework, China commits to implement two treaty-related minimum standards, namely the prevention of treaty avoidance and improving the dispute resolution mechanism. On top of that, China opts to apply articles including dual resident entities, dividends transfer transactions, capital gains from alienation of shares or interests of entities deriving their value principally from immovable property and application of tax agreements to restrict a party’s right to tax its own residents.

Now it is a good timing to encapsulate the latest development of BTTs policy in China. This study takes a close look at 14 BTTs that China revisited and 16 newly-signed BTTs since 2008, as well as the amending protocol with India in 2018 (See Table 1). The treaty partners, by their economic status, can be grouped into the developed countries, economy in transition and developing countries. More than a half of the jurisdictions are situated within the BRI ambit. Out of these 29 countries, 16 have signed or ratified the MLI, and 11 BTTs are agreed by both China and the other contracting states to be covered by the MLI. This mixed group of countries may intrigue one to explore a series of questions, such as, what are the differences between the BTTs that China signed with the developed countries and the developing countries (or economies in transition)? To which treaty model that China’s BTTs signed or revisited in the past decade are more analogous to, the OECD Model which tends to be in favor of capital-exporting states, or the UN Model which provides more tax rights to capital-importing states? Moreover, to what extent may the BTTs facilitate China’s outbound investment, particularly the BRI? Last but not the least, how will the MLI affect China’s existing BTTs? To answer the foregoing questions, this paper selects five subjects for analysis: the resident provision; the concept of permanent establishment; investment income, royalties and capital gains; relief of double taxation; and anti-avoidance rules.

II. TREATY RESIDENT

Tax treaties apply to persons who are residents of one or both contracting states. The qualification of being a resident of the contracting state(s) is thus crucial, and a prerequisite for the treaty application. Under the BTTs, a resident of a contracting state is normally defined as the person who, under the laws of that state, is liable to tax therein by reason of his domicile, residence, place of effective management or any other criterion of a similar nature. When an individual is recognized as a resident of both contracting states, i.e. a dual resident, the provision analogous to article 4(2) of the OECD Model or UN Model provides the tie-breaker rule to designate one contracting country as the resident state under the applicable treaty by reference to his or her permanent home, center of vital interests, habitual abode, nationality and etc. In case a person other than individuals is considered as a resident of two contracting states, the place of effective management (PoEM) had been traditionally used as the criteria to determine the treaty resident state in the article 4(3) of the OECD Model or UN Model prior to 2017.

Given the fact that a dual-resident company is often involved in tax avoidance arrangement and the factual determination of the PoEM usually trigger controversies in practice, the BEPS action plan 6 proposes to replace the PoEM test with the MAP mechanism by providing that ‘the competent authorities of the Contracting Jurisdictions shall endeavor to determine by mutual agreement the Contracting Jurisdiction of which such person shall be deemed to be a resident for the purposes of the tax treaty. In the absence of agreement reached by the competent authorities of two states, such a dual-resident person shall not be entitled to any relief or exemption from tax provided by the treaty except to the extent and in such manner as may be agreed upon by the competent authorities of the contracting jurisdictions.’ As a result of this change, the competent authorities are given discretion to take into account various factors on the case-by-case basis to solve the dual-residence conflict for a person other than the individual. This new provision was later incorporated into article 4(1) of the MLI, article 4(3) of the OECD Model of 2017 and the UN Model of 2017.

In China’s context, to be eligible to treaty benefits, the applicant is expected to have sound knowledge of the resident concept under both the domestic law and the applicable BTT, and fulfilling the application procedures. Under the revised IITL of 2018, the concept of Chinese resident individual has been broadened to include any individual who is domiciled in China or who is not domiciled in China but has stayed in the aggregate for 183 days or more of a tax year in China (365 days under the old law). This new resident rule enlarges China’s personal tax jurisdiction on individuals, and inevitably increases potential risks of double taxation. For enterprises, the residence is based on either the incorporation or the PoEM of the enterprises according to the EITL. In other words, an enterprise incorporated in China, or incorporated outside China but having its place of effective management located in China, is considered as a Chinese tax resident.

In China’s BTTs, the resident article is largely assimilated to article 4 of the OECD Model of 2014. According to the provisional position the SAT submitted to the MLI depositary in 2017, China opts to apply article 4(1) of the MLI to all the CTAs. This position matches with the options made by countries, e.g. the UK, Norway, the Netherlands, Czech, Romania and Russia. In the recently signed or revisited BTTs, the provision analogous to article 4(1) of the MLI has been adopted to resolve the dual residency conflict for the person other than an individual, such as the BBT with Chile in 2015, Argentina in 2018, New Zealand in 2019 and Italy in 2019, as well as the protocol with India in 2018.

Being qualified as a Chinese tax resident implies the worldwide tax liabilities of the applicant in China, as well as the accessibility to a wide range of China’s BTTs network. For the going-out enterprises, a certificate of Chinese tax resident can be a very useful amulet, which shield them from the excessively high tax burdens imposed by host countries. At domestic, the procedures for applying the certificate of Chinese tax residents have been greatly optimized under the Announcement on Issues concerning the Issuance of Certificates of Chinese Fiscal Residents which eases bureaucratic hassles and provides better protection to the applicant’s rights. Recently, the Announcement on the Adjustment concerning the Issuance of Certificates of Chinese Fiscal Residents was issued as a complement to the Announcement on Issues concerning the Issuance of Certificates of Chinese Fiscal Residents to keep update with the IITL revision. Tax agencies in some localities went a step further to establish the electronic platform to facilitate the on-line application.

For tax residents of the other contracting state, the enjoyment of benefits under China’s BTTs requires the fulfillment of the prescribed procedures. To echo the State Council’s general policy to streamline the governmental functions, delegate powers while improving regulation, the SAT issued the Announcement on Issuing the Measures for the Administration of Non-Resident Taxpayers’ Enjoyment of the Treatment under Tax Agreement in August 2015, bringing radical changes to the administration of non-residents’ application for treaty benefits. This new bulletin removes the pre-approval procedure or record-filing requirement under the previous circulars, and provides the self-assessment mechanism for non-resident taxpayers claiming treaty benefits. For non-resident taxpayers that consider themselves eligible for treaty benefits, they may inform the withholding agent and enjoy such benefits accordingly. The prescribed forms or other supporting docs are not required to be submitted until non-resident taxpayers and their withholding agents file tax return. This new rule saves non-resident taxpayers from the bureaucratic delay, but also increase the taxpayers’ risks in making assessment appropriately. In practice, to eliminate uncertainties, some non-resident enterprises applied for advance rulings from tax authorities to ascertain their eligibility for treaty benefits.

III. PERMANENT ESTABLISHMENT

Permanent establishment (PE) is a core concept under the BTTs. It matters whether a contracting state (i.e. source state) may tax business profits derived by a resident of the other contracting state (i.e. non-resident), and to what extent. In case that business activities of non-residents did not constitute the PE in the source state, the source state is prohibited by the BTTs to levy tax on profits derived by the non-resident. Under the OECD Model and the UN Model, the PE can be traditionally constituted in the source state if a non-resident have, in that state, the fixed place of business (i.e. physical PE), construction activities lasting for a specified period of time (i.e. construction PE), dependent agents authorized to habitually exercise an authority to conclude contracts on its behalf (i.e. agency PE), service preformed for the prescribed length of time (i.e. service PE) or insurance premium collected or risks insured by dependent agents (i.e. insurance PE).

As significant as it is, this concept, however, can be easily susceptible to abusive use. The BEPS action plan 7 is thus devoted to re-examine the PE concept. This report is not a wholesales revamp of the PE article, but proposes changes to a few provisions addressing certain tax avoidance scenarios, e.g. commissionnaire arrangements which are used to avoid agency PE; circumvention of construction PE through splitting-up contracts between the closely related enterprises; artificial avoidance of PE status taking use of exceptional clauses through the fragmentation of activities, etc. These proposed changes were later incorporated in articles 12-15 of the MLI, the revised PE article under the OECD Model of 2017 and the UN Model of 2017.

In the BTTs China recently revisited or signed, some salient features can be observed regarding the PE article (Table 2): in the construction PE provision, the length of time has been extended from 6 months (analogous to the UN Model) to 12 months (analogous to the OECD Model) under most recently revised BTTs. In the newly signed BTTs, the time threshold for construction PE is a mixture, ranging from 6 months, 9 months to 12 months. The inclination to adopt a longer period of time as the threshold in the construction PE provision is aligned with China’s interest to stimulate and expand the outbound construction projects in the past years. The higher threshold imposes more stringent restrictions on source state taxation. Furthermore, the majority of the BTTs contain the service PE provision analogous to article 5(3)(b) of the UN Model which provides that ‘the furnishing of services within a contracting state for a period or periods aggregating more than 183 days within any twelve-month period may constitute PE’, except with the BTTs with Ethiopia, Syria, Cambodia and Congo.

With regard to the changes advanced by the BEPS action plan 7, China takes a more conservative approach by making reservations to all the PE related articles under the MLI. China’s position is not particularly exceptional, as the adoption rate of the PE-related articles in the MLI by signatories remains low in general. Furthermore, it is believed by the SAT’s officials that the abusive exploitation of the PE article can be effectively reduced by unilateral interpretation. For instance, according to the Circular on the Interpretations on Clauses of the Agreement between China and Singapore for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes on Income and of the Protocol, an enterprise of other contracting state is considered to have an agency PE in China if such an enterprise has an agent in China who has and habitually exercises an authority to conclude contracts in the name of that enterprise. The expression of concluding contracts in the name of the enterprise is construed in the broad sense to include the concluding of a contract not in the name of the enterprise but having binding force on the enterprise. The term conclude refers not only to the act of concluding contracts itself, but also to the agent’s right to participate in the negotiation of contracts, agreement upon the clauses of contracts, etc. on behalf of the enterprise. This broad interpretation made by the SAT regarding the agency PE provision has the nearly equivalent effect with the revised agency PE article in article 12 of the MLI.

The position to make reservation on the PE articles under the MLI, however, did not hinder China from moving towards the new features under BEPS Action Plan 7, as the revised agency PE provision, the amended exceptional clause, and the paragraph on the expression of a person closely related to the enterprise are wholly or partially incorporated into the treaties China signed or revisited after 2015, e.g. the BTTs with Chile in 2015 and Argentina in 2018, the revised BTTs with Spain in 2018, as well as the protocol with India in 2018.

At domestic, practical challenges for China’s tax authorities to tackle the PE-related disputes stem from the absence of the SAT guidance in regulatory documents and the inexperience of tax officials in the non-resident’s administration. Whether a PE exists, by its nature, is a question based on the factual analysis. To ascertain the presence of a PE, it requires tax authorities to carry out intensive factual investigation, such as on-site visits, extensive interviews with the company personnel, collaboration with other government agencies at domestic and exchange information with tax authorities in other countries. The lack of experience of tax officials in information gathering, and the insufficient knowledge in the evolving business structure of non-resident enterprises (particularly in the digitalized economy) can greatly hamper the immediate detection of PE existence. In reality, only a handful of PE cases have been reported by tax authorities in China, and mostly concentrate on the specific scenarios, like PE arising from the cross-border secondment of personnel by non-resident enterprises, and sino-foreign cooperative education projects. The improvement in the monitor of PE risks by local tax authorities will hinge upon the guidance and detailed instructions given by the SAT in the near future regarding the PE assessment.

IV. INVESTMENT INCOME, ROYALTIES AND CAPITAL GAINS

Unlike business income and labor income, investment income (including dividends and interest), royalties and capital gains have a higher degree of mobility. The allocation of tax rights by the BTTs on such income thus produces more direct impacts on business location or transaction models of the investors or the right-holders.

Under China’s IIT regime prior to the reform in 2018, the schedular tax system was adopted, meaning that income derived by individuals are subject to tax by itemization, and are taxed differently based on income characterization. The revised IITL of 2018, however, introduces a mixed schedular and comprehensive system, as dividends, interest, gains from property transfer derived by individuals continue to be subject to tax on the schedular basis, whereas royalties derived by resident individuals are computed together with wages and salaries, remuneration for labor services and manuscripts for aggregate tax calculation purposes.

The EITL, on the other hand, adopts the comprehensive tax system, i.e. income of different categories is computed together to calculate the taxable income. For profits derived by resident enterprises or non-resident enterprises with the establishment or site in China, the net income is subject to tax at the rate of 25 percent; whereas profits are derived for non-resident enterprise without establishment or site in China or not effectively connected with its establishment or site in China, the gross income is subject to tax at the rate of 10 percent and is collected through the withholding agents. The withholding mechanism applied to non-resident enterprises and their withholding agents was substantially changed as the SAT issued the Announcement on the Matters regarding Withholding Enterprise Income Tax at Source for Non-tax-resident Enterprise, repealing the Notice on Issuing the Interim Measures for the Administration of the Withholding of Enterprise Income Tax at Source on Non-Resident Enterprises. This new bulletin echoes the national policy to simplify administrative procedures by removing the obligations of withholding agents to file contracts with tax authorities, abolishing the tax withholding clearance procedure for the contracts involving multiple payments, and nullifying the seven-days tax filing deadline for non-resident enterprises when non-resident enterprises need to complete the filing on its own.

A. Dividends

Under the IITL, dividends paid by a Chinese resident to a non-resident individual are subject to tax in China at the rate of 20 percent based on gross income. Taxes are withheld by the payer of dividends on the monthly or transaction-by-transaction basis. On the other hand, for dividends paid by a Chinese resident to a non-resident enterprise which has no establishment or site in China, withholding tax is levied on the gross income at the rate of 10 percent. Starting from December 1, 2017, the withholding obligation for dividends derived by non-resident enterprises arises on the date of the actual payment according to the Announcement on the Matters regarding Withholding Enterprise Income Tax at Source for Non-tax-resident Enterprise, instead of the date that the distribution decision is made as provided in the Notice on Issuing the Interim Measures for the Administration of the Withholding of Enterprise Income Tax at Source on Non-Resident Enterprises. This change allows the non-resident enterprises and the withholding agents to fully utilize the after-tax cash within China if such cash is not needed offshore. Furthermore, to incentivize reinvestment by foreign investors in China, since January 1, 2017, tax deferral has been granted to dividends distribution received by non-residents if such dividends are reinvested directly into the projects in China, and the funds are directly transferred to the invested projects from the dividend distributing entity without leaving China. In other words, the 10 percent withholding tax on dividends derived by foreign investors will be deferred until the foreign investors’ disposal of the reinvestment in China.

In both the OECD Model and the UN Model, it is provided in article 10(2) that dividends paid by a company of a contracting state (i.e. source state) may be taxed in that state subject to the prescribed rate if the recipient of dividends who is the resident of the other contracting state is the beneficial owner of dividends. In the dividends article of China’s BTTs, source state taxation is restricted subject to the split rates or a flat rate, or is prohibited if dividends are derived by governments or governmental owned entities. Where the split rates analogous to article 10(2) of the OECD Model are adopted, the substantial shareholding is distinguished from the portfolio investment. When the shareholder company directly holds at least 25 percent of the capital of the company paying the dividends, the tax rate of no more than 5 percent is provided for the source state; whereas for the portfolio investment, a higher tax rate of 10 percent or 15 percent is provided. In the majorities of BTTs China revisited, the provision which used to apply the flat rate has shifted to adopt the split rates. In the BTT with Argentina, the split rates are provided along with the most-favored nations (MFN) clause. Furthermore, in the treaties China signed with countries where the Chinese investment is destinated, such as African countries or the BRI-covered jurisdictions, a flat rate lower than 10 percent is often provided to set more stringent limits on the source state taxation. For example, In the BTT with Romania, the rate is as low as 3 percent. In a few BTTs, the source state tax exemption is granted to dividends derived by the government or the government-owned entities of the other contracting state, such as the BTTs with Switzerland, UK, the Netherlands, Romania, Spain and New Zealand.

When the split rates are adopted under the dividends article, an abusive scheme may be exploited by taxpayers to secure benefits of the lower rate by increasing shares holding shortly before the dividends become payable. To counteract such a maneuver, the BEPS action 6 introduces a minimum shareholding period by providing that treaty benefits of the lower rate shall apply only if the substantial shareholding lasts throughout a 365-day period that includes the day of the payment of the dividends. This change was incorporated in article 8(1) of the MLI which the SAT opts to apply in place of or in the absence of a minimum holding period in the provisions of all 36 CTAs containing the split rates in the dividends article (except the BTT with UK). This position matches with the option made by jurisdictions such as France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Russia, which also choose to apply article 8(1) of the MLI without reservation.

This anti-abusive measure proposed by BEPS action plan 6, in effect, has long been put into practice in China as the SAT provided in the Notice of Taxation on the Issues concerning the Application of the Dividend Clauses of Tax Agreements that, to be eligible for the lower tax rate in the substantial shareholding under dividends provision, the percentage of capital of the Chinese resident company directly owned by the fiscal resident of the other contracting party shall meet the prescribed threshold at any time during twelve consecutive months before dividends are obtained. This unilateral interpretation guards China’s tax base from potential abusive use of treaty benefits, but may trigger the risk of treaty overriding once the MLI takes effect in China. Where the other contracting state of the BTT chooses to make reservation on article 8(1) of the MLI, the application of the minimum holding requirement under the Notice of Taxation on the Issues concerning the Application of the Dividend Clauses of Tax Agreements can stand in stark contradiction with the position made by that state.

B. Interest

In the cross-border scenario, interest paid by Chinese enterprises, organizations, institution and individuals is considered as interest arising from China. The payor that is the enterprise under the EITL may claim deduction of interest payment as expense, subject to the restriction of thin capitalization rules and transfer pricing rules. Interest received by the non-resident individual is subject to 20 percent withholding tax in China, whereas interest derived by the non-resident enterprise without establishment or site in China is subject to 10 percent withholding tax.

Under the BTTs, source state taxation on the outbound payment of interest is restricted by the provision analogous to article 11(2) of the OECD Model, which provides that ‘interest arising in a contracting state (i.e. source state) may be taxed in that state according to the laws of that state, but if the beneficial owner of the interest is a resident of the other contracting state, the tax so charged shall not exceed 10 percent of the gross amount of the interest.’ In the BTTs China recently revisited or signed, more stringent control has been placed on the source state in taxing interest: for instance, tax rate lower than 10 percent is provided in the BTTs with Romania, Tajikistan, Ethiopia, Czech, Botswana and Zimbabwe; in the BTT with Russia, source state is even required to give exemption for interest payment. Furthermore, a separate exemption clause exists in all the BTTs which grants exemption to ‘interest paid to the government or any financial institutions wholly owned by the government of the other contracting state, or paid on the loans guaranteed or insured by the government or any financial institutions wholly owned by the government of such a contracting state’. In some other BTTs, the exemption is further extended to interest paid to any financial institution (e.g. BTT with Ecuador), and interest paid in connection with the sale of commercial or scientific equipment on credit (e.g. BTTs with Germany, Spain and Romania). In the BTTs with Chile and Argentina, the stipulated tax rates are provided accompanied with the MFN clause, providing that a lower tax rate in the later BTTs Chile or Argentina concluded with other countries will apply automatically to article 11(2) of the BTTs with China.

Lower tax rates in the interest article together with the widespread insertion of exemption clause on government-related loans have facilitated China’s outward financing. According to the official estimate, in the year of 2016 alone, the interest article under China’s BTTs has saved Chinese residents from taxes for more than RMB 27 billion at host states, which not only enhances the competitiveness of Chinese financial institutions, but also reduces financial costs for China’s going-out enterprises. This tax-saving benefit has great significance particularly for China’s BRI initiative, as Chinese banks (e.g. China Development Bank and the Silk Road Fund), in conjunction with international banks of which are Chinese-initiated projects (e.g. the Asia Development Bank and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank), have been playing a predominant role in structuring the financing of infrastructure investment.

C. Royalties

Under the IITL and the EITL, royalties are defined as income obtained by enterprises and individuals from providing the right to use patent, trademark, copyrights, non-patented technologies and other franchises. The sourcing rule, however, differs in these two regimes: in the IITL, royalties are considered as China-sourced if the right to be granted is used in China, whereas under the EITL, royalties are deemed to be sourced from China when the payor, i.e. the enterprise, the institution or the establishment and individual that pays royalties or bears the payment, is located in China.

Prior to the IIT reform in 2018, royalties derived by non-resident individuals were subject to withholding tax in China at the rate of 20 percent, and the taxable income was computed by deducting RMB 800 or 20 percent of the gross income. In the revised IITL of 2018, from January 1, 2019, progress rates ranging from 3 percent to 45 percent in seven brackets applies to royalties derived by non-resident individuals. Tax is levied through withholding on the monthly or transaction-by-transaction basis, and the taxable amount is computed by deducting 20 percent of gross income as expense.

For royalties derived by foreign enterprises, before the unification of EIT in 2008, foreign enterprises may apply for tax exemption if certain conditions were met and with governmental approval. As this preferential treatment was removed by the EITL, from January 1, 2008, royalties derived by non-resident enterprises without establishment or site in China or not effectively connected with its establishment or site in China are subject to withholding tax at the rate of 10 percent. The resident enterprise that makes the outbound payment of royalties is the withholding agent and may claim the deduction of royalties as expenses subject to transfer pricing rules.

Tax allocation rules provided in the OECD Model and the UN Model regarding the royalties are different in several aspects: in the OECD Model, the state of which the recipient is a resident (i.e. resident state) enjoys the exclusive right to tax royalties, whereas the UN Model allocates tax rights within a certain limit to the state where royalties arise (i.e. source state); in terms of the scope of royalties, the definition provided in the UN Model is broader to include the consideration for the use of, or the right to use, industrial, commercial or scientific equipment, and this expression was deleted from the OECD Model in 1994. Last but not the least, article 12A of the latest UN Model of 2017 includes a separate article on fees for technical services in parallel to the royalties article in the view that many developing countries have faced substantial risks from base erosion and profit shifting through the manipulation of royalties payments. Under this article, fees for technical services are defined as payments for services of a managerial, technical or consultancy nature, and the state of which the payor is a resident is entitled to tax such fees, even technical services are not provided in that state.

In terms of exclusive rights and royalties, China has long been a net importing country. It is thus unsurprising that the royalties article under China’s BTTs are more aligned with the features under the UN Model. Most of the BTTs adopt the definition in article 12(3) of the UN Model to include the ‘consideration for the use of, or the right to use, industrial, commercial or scientific equipment’. The source state is granted the right to tax royalties within certain limits. For the ‘consideration for the use of, or the right to use, industrial, commercial or scientific equipment’, some BTTs provide a lower tax rate or the reduced tax base to be applied. A separate article on fees from technical service appears in the BTTs with Cambodia and Kenya, providing that the contracting state in which the fees for technical services arise may tax such fees not exceeding 10 percent of the gross amount if the beneficial owner is a resident of the other contracting state.

As royalties arise mainly from licensing intangible rights which often mingles with the provision of services, most disputes regarding the royalties article in China revolve around income characterization. Whether certain income is characterized as royalties or service fees, is crucial to the source state taxation. In case that income is defined as royalties and is deemed China-sourced, the payor may claim the deduction of payment as expense in China whereas the non-resident recipient is subject to withholding tax in China regardless whether its business operations constitute the PE in China. If such income, however, is considered as service fees, the payor may claim the deduction of payment but the non-resident recipient will not be taxed in China unless it has a PE in China. To counter the base erosion arising from the excessive payment of royalties, the SAT issued the Notice on the Issues Relevant to the Implementation of the Royalty Clauses in Tax Treaties and the Notice on the Issues Related to the Implementation of Tax Treaties, to provide guidance for local tax bureaus in making distinction between royalties and service fees on the one hand, and released the Announcement on Issues concerning Enterprise Income Tax on Expenses Paid by Enterprises to Their Overseas Affiliates, which is later replaced by the Announcement on Issuing the Measures for the Administration of Adjustments under Special Tax Investigation and Mutual Agreement Procedures, to set restriction on the deductibility of royalties payment not in compliance with arm’s length principle, on the other.

D. Capital Gains

Capital gains refer to income arising from alienation of properties, including immovables, movable and other interests or rights. When non-resident individuals transfer immovables situated in China or alienate other properties in China, the net gains derived are subject to withholding tax at the rate of 20 percent in China. For non-resident enterprises that receive the China-sourced gains from alienation of properties, the net gains are subject to withholding tax rate of 10 percent in China.

Under the capital gains article of the OECD Model, tax powers of contracting states are allocated following the rules that: first, gains from alienation of the immovable property may be taxed in the state where immovable property is situated; second, gains from alienation of movable properties forming parts of the PE may be taxed in the PE state; third, gains from alienation of shares in the company that derive value principally from immovable properties (more than 50 percent) may be taxed in the state where the immovable property is situated; and fourth, gains from other properties not specified in above provisions are taxable exclusively by the resident state, i.e. the state of which the alienator is the resident. In addition, the UN Model contains a provision which does not find its comparable in the OECD Model, and grants tax rights to the source state when gains are derived from alienation of shares by the alienator which owns a substantial interest in the company. According to article 13(5) of the UN Model of 2011, gains, other than those to which paragraph 4 applies, derived by a resident of a Contracting State from the alienation of shares of a company which is a resident of the other Contracting State, may be taxed in that other State if the alienator, at any time during the 12-month period preceding such alienation, held directly or indirectly at least ___ percent of the capital of that company.

To better protect source state taxation and counter the abusive scheme used by taxpayers to dilute the value of shares deriving from immovable properties prior to the alienation of shares, the BEPS action plan 6 proposes to revise article 13(4) of the OECD Model by firstly, extending the scope from ‘gains from alienation of shares’ to ‘gains from alienation of shares or comparable interests, such as interests in a partnership or trust’; and secondly, adding the period of time, i.e. during 365 days preceding the alienation, in evaluating the value of share deriving from immovable properties. These two elements are then incorporated into articles 9(1)(b) and 9(1)(a) of the MLI, as well as article 13(4) of the OECD Model of 2017 and the UN Model of 2017.

The majorities of China’s BTTs contain the provision analogous to article 13(4) of the OECD Model and the UN Model, except for the BTTs with Syria and Czech. Two changes proposed by the BEPS action plan 6 are adopted in article 13(4) of the BTTs with France, Chile, Kenya and Argentina, but the time period varies from 365 days to 3 years. In the provisional position, the SAT opts to apply article 9(1)(b) of the MLI, i.e. the enlarged scope to include the alienation of interests in other entities, to 81 BTTs which contain the provision analogous to article 13(4) of the OECD Model, but makes reservation on article 9(1)(a) regarding the 365 days time period. The SAT’s reluctance to embrace article 9(1)(a) may be attributable to the fact that this 365-days period contradicts with the time requirement the SAT put forward in its unilateral interpretation in 2012. Pursuant to the Bulletin on Relevant Problems regarding the Capital Gains Provision under Tax Treaties, ‘gains from alienation of shares deriving value principally from immovable properties in China’ means that the value of immovable properties in China held, directly or indirectly, by the company whose shares are transferred reaches more than 50 percent of the total value of the properties of the company during 36 consecutive calendar months before the transfer of shares of the company (not including the current month of the transfer). Compared with article 9(1)(a) of the MLI, the 36 months period provided by the SAT is much preferable for the source state taxation. However, in some recently signed treaties, e.g. the BTTs with Kenya in 2017 and Argentina in 2018, the expression of 365-days appears in article 13(4), indicating China’s flexibility to accept the time threshold given by the BEPS actions. It remains to be seen what final position China may take regarding article 9 of the MLI at the ratification of the convention.

As to ‘gains from alienation of shares in the substantial shareholding’, it is noted that the provision analogous to article 13(5) of the UN Model exists in all the BTTs China revisited with developed countries, but is absent in the most BTTs China signed with developing countries or transitional economies. Under such a provision, when the alienator of a contracting state holds at least 25 percent in the capital of the company in the other contracting state, at any time during the 12-month period preceding such alienation, the other contracting state, i.e. the state of which the company is a resident, may tax such gains. In the BTTs with Czech, Chile and Argentina, the source state is given large room to tax gains from shares transfer as no threshold is provided regarding the shareholding ratio, whereas in the BTT with Zimbabwe, the threshold for the substantial shareholding is set as high as 50 percent. These differentiated treatments are aligned with China’s dual economic status as a big FDI destination for developed countries on the one hand, and a large outbound investor to developing countries on the other.

V. RELIEF OF DOUBLE TAXATION

In China, tax residents are subject to tax for the global income. To relieve double taxation, foreign tax credit is provided under both the EITL and the IITL, allowing Chinese residents to claim a credit against their Chinese taxes for taxes paid to other countries. Virtually, tax paid abroad can reduce Chinese tax revenue dollar for dollar. Under the IITL, the credit is given based on a country-by-country and an item-by-item basis, while in the EITL, the direct foreign tax credit is operated on a country-by-country basis. Besides direct tax credit, the EITL also provides the indirect tax credit which allows resident enterprise taxpayers to claim a credit against underlying foreign taxes paid on dividends and profits distribution from equity income from their directly or indirectly controlled foreign companies (CFCs). As China’s outward investment has experienced exponential growth in recent years, to boost the competitiveness of Chinese companies in the global market, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and the SAT jointly issued the Notice of Taxation on Issues concerning Improving Tax Credit for Overseas Income of Enterprises in December 2017 to provide more generous tax credit for resident enterprises. Under this circular, from January 1, 2017, besides the country-by-country credit, resident enterprise taxpayers may opt for integrated credit method under which the limitation of foreign taxes can be averaged in high-tax and low-tax countries; moreover, the indirect tax credit, which used to be limited to the CFCs in three tiers, is now extended to the CFCs in five tiers.

Under China’s BTTs, the measures taken by China to relieve double taxation is rather standardized, including both direct tax credit and indirect tax credit. For indirect tax credit, it is provided that where a dividend is paid by a company which is a resident of the other contracting state to a Chinese resident company which owns not less than 20 percent (or 10 percent) of the shares of the company paying the dividend, the credit shall take into account the foreign tax paid by the company paying the dividend in respect of its income. A notable change under the article of the Elimination of Double Taxation is concerned with the tax sparing provision under which the resident state agrees to grant relief with respect to the source taxes that have not actually been paid. Tax sparing provisions used to exist in most BTTs that China signed with developed countries in the 1980s, but was all removed from the revisited BTTs. The underlying reasons can be attributable to China’s changing economic status as well as the pervasive concerns that tax sparing provision is usually used for abusive tax planning. Only two BTTs signed after 2008 contain the tax sparing provision, i.e. the BTTs with Ethiopia in 2009 and Cambodia in 2016.

In practice, the written rules of tax credit mechanism in China, however, have not been implemented in a satisfactory way due to various barriers. One of the reasons is that information about foreign-sourced income of China’s residents are not often accessible to Chinese tax authorities timely or sufficiently. When taxpayers fail to disclose information of foreign income voluntarily as required by the law, tax officials have very limited channels to collect such information. Moreover, the existing rules of the credit system, as commented by taxpayers and tax officials, are far too complicated to be understood and implemented, especially the indirect tax credit. Even the newly-introduced and taxpayer-friendly rules under the Notice of Taxation on Issues concerning Improving Tax Credit for Overseas Income of Enterprises cannot diminish ambiguities or uncertainties faced by tax practitioners. In recent years, as global tax reforms have witnessed a general trend in countries moving towards cutting income tax rates or shifting from global tax system to territorial system by exempting profits earned offshore, the lowering tax burdens in host states create less incentives for Chinese taxpayers to report income earned abroad. This is particularly true when tax preferential treatments are provided in host states and the tax sparing provision is absent under China’s BTTs.

To address these problems, there is a rising outcry in practice and academia that, to increase the competitiveness of Chinese resident enterprises and encourage capital repatriation, the exemption system shall be introduced in China, rules to relieve double taxation be simplified and tax sparing provisions be included in the newly signed BTTs. Furthermore, the automatic exchange of financial account information under the common reporting standard (CRS) between China and other jurisdictions starting from September 2018 will be of great help to improve the capacity of tax administration to gather information. It is also anticipated that the upcoming revised Law on Tax Collection and Administration would introduce a new chapter on information disclosure, tightening up requirements on taxpayers, financial institutions, other governmental agencies and third parties to provide tax-related information. These factors will undoubtedly exert visible impacts on the implementation of tax credit system in China.

VI. ANTI-AVOIDANCE RULES

As the importance of the BTTs began to emerge in China in 2008, the risks of abusive use of the BTTs also drew increasing attention. Since 2009, a set of measures have been taken by the SAT to counter abusive use of the BTTs, including the continuous refinement of the interpretation on beneficial ownership, revising capital gains article to prevent tax avoidance in (indirect) shares transfer, and insertion of anti-avoidance rules of different forms into newly signed treaties. These measures stand as a shield to guard treaties from being used in an inappropriate way and to protect China’s fiscal interests. Meanwhile, anti-avoidance rules in domestic income tax laws are gradually taking shape, reflected by the provisions under chapter six of Special Tax Adjustment in the EITL and article 8 of the newly revised IITL of 2018.

In the global arena, the BEPS action 6 are the collective actions agreed upon by countries to fight against abusive use of tax treaties, in particular, treaty shopping. Consensus has been reached upon by jurisdictions to include a clear statement in the preamble of treaties that BTTs are entered with the intent of states to avoid creating opportunities for non-taxation or reduced taxation through tax evasion or avoidance. Besides, as a minimum standard under BEPS actions, the member states of the BEPS Inclusive Framework commit to incorporate into treaties: the principal purpose test (PPT), or the PPT with a simplified Limitation of Benefits (LoB) rule, or the LoB clause with a mechanism designed to deal with conduit arrangements. The output of BEPS action 6 is later translated into articles 6 and 7 of the MLI, as well as the article of entitlement to benefits in the revised OECD Model of 2017 and the UN Model of 2017. China, as the majority of MLI signatories, commits to apply article 6 and the PPT rule under article 7(1) of the MLI.

A. Beneficial Ownership

Beneficial ownership is an important concept under the articles of dividends, interest and royalties to determine whether the income recipient of a contracting state may be eligible to treaty benefits in the other contracting state. Despite of its significance, the meaning of this term is far from unanimous among countries for decades.

In China’s context, after tax exemption granted to foreign investors for deriving China-sourced dividends and royalties was removed by the EITL in 2008, the treaty shopping scheme soon became rampant, as more and more non-resident enterprise taxpayers set up the intermediate holding companies in Hong Kong, Barbados and Mauritius in order to reap benefits of lower tax rates (5 percent) provided by the BTTs China signed with those jurisdictions. As a countermeasure, since 2009, the SAT has issued five circulars in total to provide interpretation on the term of beneficial ownership. Among them, the Bulletin on Beneficial Ownership under Tax Treaties represents the most recent efforts made by the SAT to interpret this term. This bulletin applies to transactions in which tax liabilities or withholding tax liabilities arise on and after April 1, 2018. The drafting of this administrative guidance takes into account the nearly ten-year experience of tax authorities in applying this term, and is aligned with the spirit of the BEPS action plan 6 by focusing on the substance of the entity. For instance, the concept of substantial business activities was introduced to examine the risks actually borne by the income recipient, functions performed as well as assets and personnel owned. On the basis of the previous circulars, the Bulletin on Beneficial Ownership under Tax Treaties refines the negative factors to identify beneficial owners, expands the safe harbor rule to a wider scope of the designated parties, and introduces the derivative benefits test which allows the recipient of dividends to enjoy treaty benefits even when it does not fulfill the conditions to be qualified as a beneficial owner. To provide clarification, this bulletin was issued along with an official interpretation note which contains concrete examples and hypothetic cases as reference.

B. Limitation of Benefits Clause, PPT Provision and Other Anti-avoidance Rules

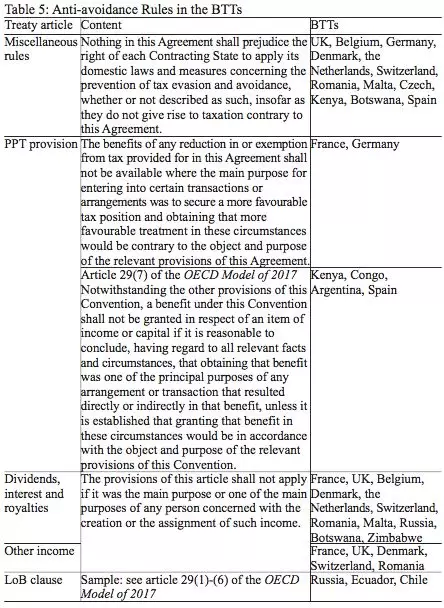

Anti-avoidance rules in China’s BTTs take different forms (see Table 5). In some treaties, it is provided in the article of Miscellaneous Rule dealing with the relationship between domestic anti-avoidance rules and BTTs. Under this provision, the BTT does not prejudice the right of the contracting state to apply its domestic anti-avoidance rules. In some other treaties, the specific anti-abuse rule, i.e. LoB clause, is included which limits the availability of treaty benefits to entities that meet certain conditions. These conditions, which are based on the legal nature, ownership in, and general activities of the entity, seek to ensure that there is a sufficient link between the entity and its resident state. Such LoB provisions are currently found in China’s BTTs with Russia, Ecuador and Chile, and are very likely included at the wish of those jurisdictions.

In the BTTs with France and Germany, a separate article on PPT is provided, stipulating that treaty benefits are not available where the main purpose of the transactions is tax-oriented, and securing such tax benefits would be contrary to treaty purposes. In some other BTTs, the PPT is not provided in a separate article, but is included in the articles of dividends, interest, royalties or other income. According to the provision position the SAT submitted to the MLI depositary, China opts to apply the PPT under article 7(1) of the MLI which shall apply in place of the existing PPT rule under the specified CTAs, or in the absence of provisions in CTAs. This provision provides that ‘notwithstanding any provisions of a CTA, a benefit under the CTA shall not be granted in respect of an item of income or capital if it is reasonable to conclude, having regard to all relevant facts and circumstances, that obtaining that benefit was one of the principal purposes of any arrangement or transaction that resulted directly or indirectly in that benefit, unless it is established that granting that benefit in these circumstances would be in accordance with the object and purpose of the relevant provisions of the Covered Tax Agreement.’ In the notification regarding article 7 of the MLI, China made a mention of all the existing BTTs which contain the PPT provisions. In addition, the provision analogous to article 7(1) of the MLI has been incorporated in the BTTs China signed in recent two years, such as the BTTs with Kenya in 2017), Congo in 2018, Argentina in 2018, Spain in 2018, New Zealand in 2019 and Italy in 2019.

China, like the majorities of the MLI signatories, chooses the PPT rule for some obvious reasons: the PPT rule is a default and self-standing option (the easiest way) that meets the minimum standard, and it is also regarded by tax administrations of the signatories to be the most preferable option as it would give them more discretionary power than the detailed and complex LoB rule. While the LoB clause is based on objective criteria and provides more certainty, it is limited to specific treaty shopping situations. PPT clause, however, has a broader scope, and the analysis of one of the principal purposes is more subjective heavily relying on the proof provided by taxpayers. However, it shall not be ignored that the application of the PPT rule is not without risks and challenges: the PPT was characterized as an extremely vague legal instrument leaving ample discretion to tax authorities, which raises legitimate concerns about the compatibility of the PPT with the principles of legal certainty and proportionality that are closely related to the rule of law. As pointed out sharply by some tax experts, there is every reason to fear that, once the MLI is in force and a large number of countries (including ones with tax authorities that do not have a reputation for predictable interpretation of tax treaties) begin to apply the PPT, this would ‘jeopardize the proper functioning of tax treaties and fundamentally undermine the reliance placed on the system’. This could be ‘dangerous to developing countries and could either choke off FDI or make it more expensive for the recipient country.’ Such a concern may explain the absence of the PPT clause in most of the BTTs China signed with developing countries.

VII. CONCLUSION

This research traces the development trend of China’s tax treaty policy in the past decade. Some findings can be drawn out from this study: in the BTTs China signed with developed countries and developing countries (or economies in transition), a few notable differences did exist, contingent upon China’s position as a capital importer or a capital exporter. Examples include the differentiated tax rates in the dividends article, whether ‘gains from disposition of shares in the substantial holding’ are subject to tax in source state, and whether the PPT rule is included as the anti-avoidance rule. Furthermore, to be compatible with the national going-out policy, certain provisions in China’s BTTs which used to be analogous to the UN Model are now shifting towards the OECD Model so to impose more stringent restrictions on source state tax. For instance, the time threshold of the construction PE in the BTTs China revisited with developed countries has been prolonged from 6 months to 12 months, and the taxation of source state on cross-border payment of interest are subject to increasing restrictions in the BTTs China signed with jurisdictions within the BRI ambit. Meanwhile, the BEPS actions plan launched in 2013, particularly the release of the MLI in 2017, is producing, or will produce profound impacts on China’s BTTs, as China opts to apply a set of provisions to the chosen CTAs, and meanwhile, the treaty-related measures under the BEPS actions have been transplanted, on the selective basis, into BTTs China signed after 2017. Before the MLI takes effect in China, it becomes imperative for the SAT to review the existing administrative interpretation which may potentially contradict with the implementation of the MLI, and to make necessary rectification.

Regarding treaty implementation, as a response to the national policy to improve business environment for foreign investors and provide stimulus for Chinese companies going abroad, the MoF and SAT have taken effective measures in recent years to reduce bureaucratic hassles and simplify administrative procedures to facilitate taxpayers’ access to treaty benefits. Meanwhile, it has been and will continue to be an important battlefield for Chinese tax administration to fight against treaty shopping to protect the country’s tax base from erosion. Despite the progresses that have been made in the past decade, grey areas and ambiguities remain in China’s BTTs implementation, such as the PE assessment and tax credit rules, for which further clarifications are needed and welcome in the near future.