LEGAL METHODS TO RESOLVE NON-PERFORMING LOANS: UNDER THE BACKGROUND OF MARKET-ORIENTATED SOLUTIONS

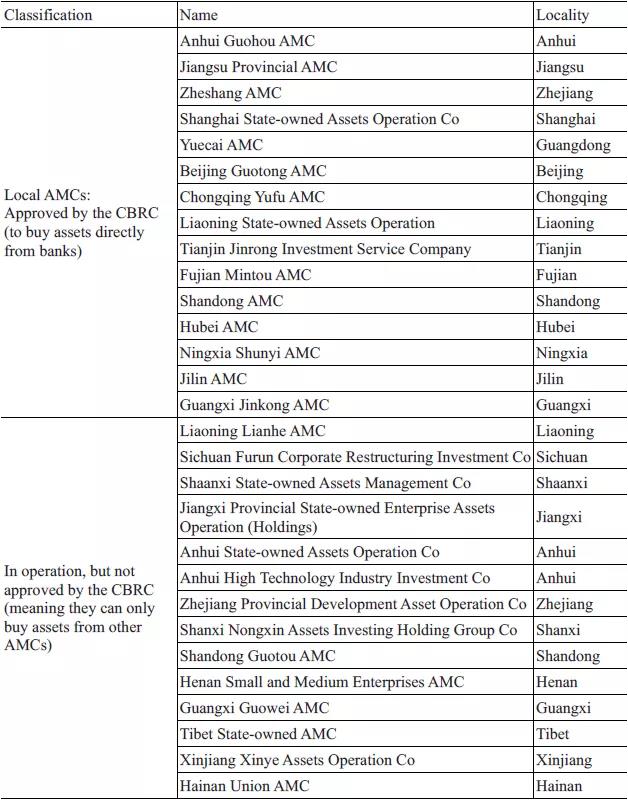

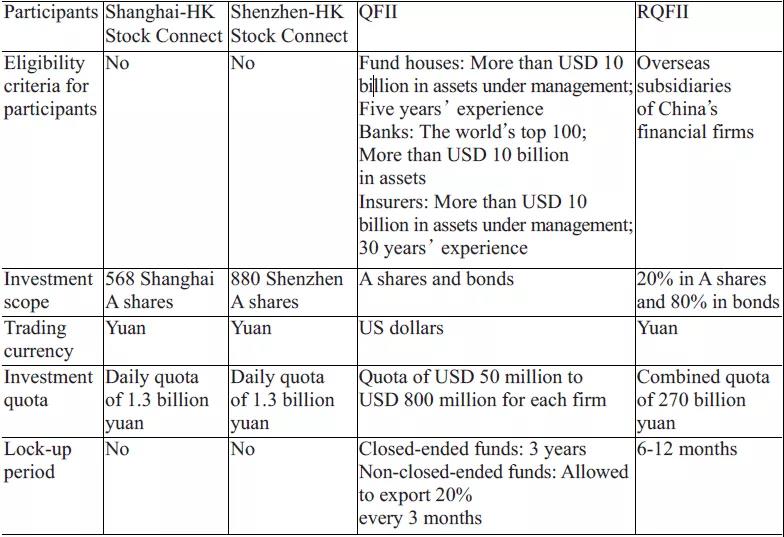

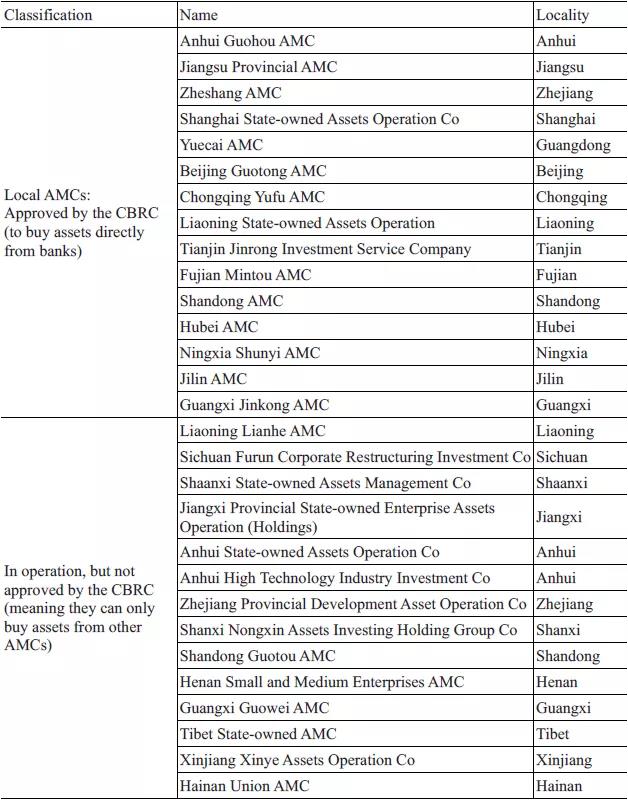

The extent of China’s non-performing loans (NPLs) is uncertain given the non-transparency of China’s state-owned banking sector and banking regulatory regime and lenient standards of recognizing NPLs. The real level of bad debt therefore is higher than the official figure may suggest. The ratio of China’s outstanding corporate debt to GDP is higher than that in Japan. This high debt level not only demonstrates the increasing financial burdens for indebted corporations but also the deteriorating status of commercial banks and the heightened systemic risks in the real economy, showing a high likelihood of economic destabilization. This article analyzes various means of disposing of NPLs and inefficacy of such means. More importantly, this article tries to find out solutions to resolve such inefficacy.This article is structured as follows. Part I clarifies the classification and resolution methods of NPLs and provides an overview of asset management companies (AMCs) as the principal means of disposing of NPLs. Part II reviews traditional solutions to NPLs. Part III discusses new solutions to NPLs and provides assessment of those actions. Part IV concludes with experience and lessons to dispose of NPLs and debt crisis.I. CLASSIFICATION AND RESOLUTIONS OF CHINA’S NON-PERFORMING LOANSNPLs were once the great trouble to China’s banking and financial systems. When China joined the WTO, the Big Four banks were on the edge of technical insolvency with a 20 percent or so NPLs ratio. The latest global financial crisis worsened China’s banking sector by burdening it with more NPLs. China’s NPL market is massive and is getting even bigger due to the slowing economy which is being further aggravated by the effects of the trade war with the US after 2018. As of June 2018, China’s commercial banks reported nearly 2 trillion yuan (USD 282 billion) of NPLs on their balance sheets. Adding in the approximately 4.3 trillion yuan (USD 620 billion) of NPLs on the books of the AMCs, China’s distressed asset market is the world’s largest one. The Chinese government data shows a record high of 3.02 trillion yuan (USD 466.9 billion) in non-performing assets in 2020. The growing NPLs create systemic risks to China’s financial system and economic growth.As China’s high-growth phase winds down, excessive debt has not only become a major financial burden for indebted corporations but has also heightened systematic risk in the financial system because of the stress inflicted on lenders by the growth of NPLs. Nevertheless, China’s NPLs have been managed at a reasonably low level, without substantially detrimental to the financial sector’s soundness and stability even though both Chinese banks and financial regulators are facing an uphill task in controlling NPLs.A. Classification of NPLs and Methods of NPL ResolutionIn 1998, a loan classification system was introduced by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), China’s central bank, after the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Under this system, bank loans are classified and provisioned as follows: performing (0 percent), watch-list (5 percent), substandard (30-50 percent), doubtful (50-75 percent) and loss (75-100 percent). The last three categories are considered as NPLs. By 2002, a five-category loan classification system was fully implemented by all banks. Traditional NPL resolution methods include (i) direct sale; (ii) restructuring/liquidation: a number of small-sized financial institutions became insolvent after several bank runs; and (iii) securitization. A private sale of NPL is usually conducted via a court administrative process. Portfolio sales (defined as being of three or more loans) consisting of multiple asset classes (e.g. real estate and shipping) that may drive the value must be conducted by AMCs through a public auction process.A sale by an AMC is conducted either by a public auction or privately through the pilot programs discussed below. The special purpose vehicle (SPV), often in a standard form, for the acquisition of the NPL portfolio must be governed by the law, with minimal room for the successful bidder to negotiate changes. Adequate due diligence on the portfolio is therefore critical from an investor’s perspective.The financing of the acquisition of Chinese NPLs will be akin to financings in other jurisdictions. A lender will typically lend funds to the SPV making the acquisition and have rights over the account from which the debt will be serviced on each interest payment date. Similarly, the standard security package that a lender expects to receive in respect of a Chinese NPL portfolio includes account pledges, assignment of contracts, and assignment of rights under the share purchase agreement and a receivables pledge over the NPL portfolio and related security.If the cash flows on bonds issued by the AMCs generated from the NPLs fail to meet the interest or principal obligations on the securities, investors could face a loss. To protect investors against such risks, external credit enhancement is necessary in addition to internal collateralization. Investors focus on methods and timeframes associated with enforcement of debts. Enforcement of a debt is entirely court-based, and self-help remedies are not available to a creditor. To procure repayment of a debt (even where secured, as the vast majority of Chinese NPLs are), the creditor must sue the debtor in court, obtaining judgment for the amount due, and then taking enforcement action through a court-administered auction process. The statutory limitation period in relation to taking action for the repayment of overdue debts is three years, and that period can be reset by serving a demand for payment on the debtor (or guarantor/security provider, as appropriate).Court-based enforcement is also the most common route in China. Some creditors may rely on debt collection companies for help but they may involve some violence or statics in the grey area. 6-12 months through the court process is the timeline for recovery in the black-letter rules. But 24 months from commencement of lawsuit to receiving funds is a conservative timeline.B. Asset Management CompaniesIn 1999, the Chinese government, through the Ministry of Finance (MOF), created four AMCs, each with approximately 10 billion yuan registered capital, with the mandate to purchase and manage the substantial amount of NPLs from the Big Four banks. These four AMCs were established and capitalized by the MOF. The purpose of creating these AMCs was to reduce the volume of NPLs in the amount of over 1.4 trillion yuan (USD 169 billion) (equivalent to nearly 20 percent GDP in the same year) on the balance sheets of the Big Four banks, and to regain the reputation and international competitiveness of the Big Four banks. The MOF, the PBOC, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) jointly supervise the AMCs.In order to divest NPLs from the Big Four banks, the government transferred the Big Four banks’ NPLs to the four AMCs in different time periods. Each AMC was assigned to one of the Big Four banks. Each AMC, acting as a bad bank, bought a percentage of the respective (good) bank’s NPLs as par value in return for bonds.In 2004, the four AMCs to the Big Four banks (hereinafter referred to as the Big Four AMCs) were permitted to make additional investments in foreclosed assets, offer custodian and agency services, and acquire distressed assets in a market-oriented manner. This represented the beginning of a transition towards market-oriented diversified financial business operations of the Big Four AMCs. Their business scope now is wide enough to invest in NPLs of banks, non-bank financial institutions and non-financial institutions, turning them to be the dominant buyers of NPLs in China. Since 2010, the Big Four AMCs have become fully marketized (i.e. they have been exposed to market forces) by acquiring NPLs through market-driven mechanisms such as biddings and auctions. By 2016, all Big Four AMCs completed the joint-stock reform by converting them into joint stock companies for possible domestic or overseas initial public offerings (IPOs). Over the years, however, the AMCs have gravitated away from their core NPL business and have become true financial conglomerates, with direct lending arms and interests in banks, securities, trust and leasing companies. While the diversification was natural to a certain extent, the AMCs have also been overextending themselves and straying from their intended purposes. Consequently, they may somehow act like banks channeling through funding and likely involve systemic risks with overburdened debts. Apart from the Big Four AMCs, there are other AMCs established at local levels as indicated in Table 1 below.Table 1: The AMCs at Local Levels

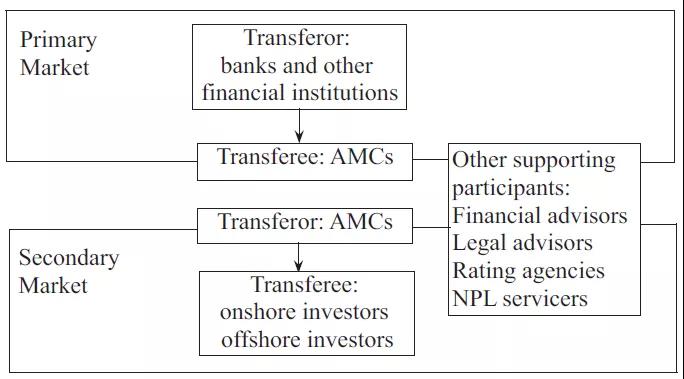

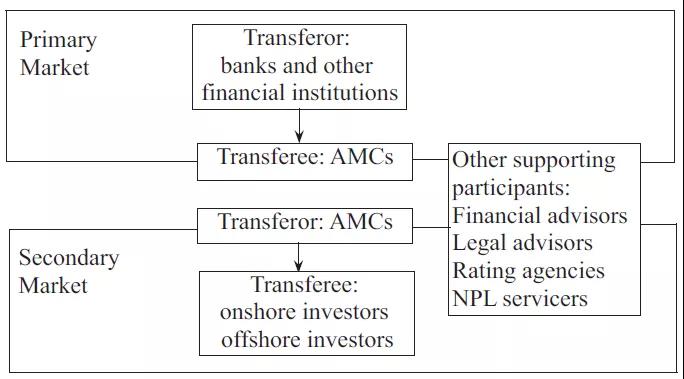

In 2012, the AMCs at the provincial level were allowed to be established by the MOF and the CBRC. In 2012, each provincial government was allowed to establish one local AMC to participate in the bulk acquisition and disposal of NPLs from financial institutions within its own province, with the disposal method being limited to debt restructuring. In December 2013, the CBRC released its requirement of additional qualifications for the set-up of provincial AMCs, including (a) 1 billion yuan in paid-up registered capital; (b) professional teams with requisite experience in the financial field; (c) good corporate governance. Since 2016, the Central Government has introduced a series of supportive policies, permitting each provincial government to establish one more local AMC, which is allowed to dispose of NPLs, among other methods, by transferring the NPLs to other investors without being subject to geographic limitation (including offshore investors).C. Purchase of NPLs from Banks by AMCs and Other Qualified Investors: The Primary MarketChina’s NPL market can be classified into the primary market and the secondary market as indicated in Figure 1 below. In the primary market, the key players include banks and financial institutions whereas the secondary market includes onshore and offshore investors. Figure 1: Purchase of NPLs

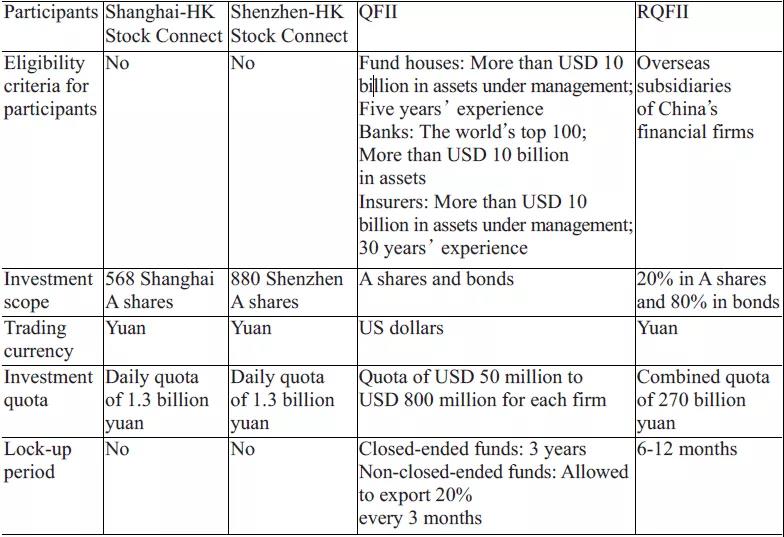

In the primary market, banks and other financial institutions sell their NPLs to AMCs, and AMCs then disposed of the NPLs via multiple means, one of which is to sell the NPLs in the secondary market to other investors (including both onshore and offshore investors). The sale process is subject to a diverse set of laws and regulations in China, and special approval requirements are applicable to the transfer to offshore investors.In the primary market, banks and other financial institutions may transfer NPLs in batches to AMCs. The bank determines the amount and type of NPLs to be sold and carries out due diligence on the NPLs to evaluate the NPLs and form the transfer or sale plan. After the transfer plan has been reviewed and filed, the bank invites interested AMCs to conduct due diligence on the target NPLs. The sale is required to be conducted via competitive means (such as bidding and auction) in order to maximize the sales proceeds. The winning bidder enters into a NPLs transfer agreement with the transferor. Both parties should, within the agreed period, issue public announcement to inform the debtors and the guarantors of NPLs regarding the occurrence of the transfer. Without proper announcement, debtors and guarantors may challenge the validity of the sale.D. Purchase of NPLs from AMCs by Investors: The Secondary MarketTo transfer NPLs in the secondary market, an AMC is required to disclose the basic information of the target NPLs including the nature, size and maturity of the NPLs on its public website as well as a designated newspaper. In particular, for any disposal of NPLs whose book value is more than 10 million yuan but less than 50 million yuan, an announcement must be made in a newspaper at the municipal level or above. For any disposal of NPLs whose book value is more than 50 million yuan, an announcement must be made in a newspaper at the provincial level or above. The announcement period should generally last for at least 10 to 20 working days. The transfer process in the secondary market should also be carried out by competitive means, including but not limited to bidding, auction, invitation to offer and public inquiry/solicitation. The AMCs have to transfer NPLs to non-state-owned transferees in the public competition process. The NPLs transfer agreement after the process is concluded between the AMC and the winning bidder. Public announcement regarding the transfer needs to be issued by the AMC to notify debtors about the repayment of outstanding debts to relevant transferee. Public announcement is the precondition for a valid sale which binds buyers and debtors.Aside from direct sales and securitizations, the main NPL disposition methods adopted by the AMCs include debt collections, sales or lease of real property, restructuring of debt terms, and bankruptcy settlement. One of the main obstacles that AMCs encounter in their debt collection efforts is created by their own and debtors’ status as the state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The state ownership creates a moral hazard issue inhibiting effective recovery and collection. Another impediment is the AMC’s inability to seek a remedy when companies, typically SOEs, reneged on the debt restructuring contracts they entered into.II. TRADITIONAL SOLUTIONS TO NPLSIn the early reforms, the Chinese government had taken a series of measures designed to build a strong banking system including: establishment of four AMCs, offshore IPOs of the Big Four banks, recapitalization of the commercial banks, and introduction of foreign investors as instruments for dealing with bad debt.A. Spin-off and Asset Management CompaniesIn 1999, the Chinese government, through the MOF, created four AMCs, each with approximately 10 billion yuan registered capital, with the mandate to purchase and manage the substantial amount of NPLs from the Big Four banks. These four AMCs were established and capitalized by the MOF.These AMC were given a budgetary life span of 10 years with the guidance of the CSRC and MOF. In 1999-2000, these AMCs bought 1.4 trillion yuan NPLs at their full-face value, dollar-for-dollar, which was approximately 19 percent of the total loans of Big Four banks. With this purchase, the NPLs ratio of the Big Four banks was reduced from 35 percent to 25 percent. According to the original plan, after the NPL portfolios were worked out, the AMCs would be closed and their net losses crystallized and written off.In order to divest NPLs from the Big Four banks, the government transferred the Big Four banks’ NPLs to the four AMCs in different time periods. For instance, in the ICBC’s massive IPO, 23 strategic investors, including China Huarong Asset Management Co., Ltd. and China Orient Asset Management Co., Ltd. (with 1.5 billion yuan and 0.5 billion yuan in the value of shares allocated respectively), contributed 18 billion yuan in total to ensure a successful IPO. As the Big Four banks were freed from massive NPL burdens, they were able to attract blue chip strategic investors when they were listed overseas. The AMCs, on the other hand, tried to recover the purchased assets as much as possible through debt equity swaps, securitization, leasing, asset restructuring and outright asset sales.These AMCs purchased NPLs from the banks, in exchange for bonds issued to the banks by the AMCs. This wiped out the debt obligation of a SOE to its bank and substituted the debt with equity ownership in the SOE by the AMC(s) that took over the NPL in question from the bank. The AMCs would then be entitled to dividends and subsequent share repurchases from the SOEs at agreed-upon prices within ten years, should the latter ever become profitable. Further, local governments were often required to guarantee that the AMCs get first priority in exiting their equity stake through public listings or a change of control event. The bonds issued to the Big Four banks in return for the NPLs were mostly ten-year bonds with a very low annual yield of 2.25 percent. The NPLs were generally sold to the AMCs at full face value though later transactions were sometimes made at substantial discounts.The AMCs were further commercialized by the Chinese government from 2007 under which their roles expanded further into IPO projects as well as consulting services. In addition, China sought to attract foreign investment into bad banks by allowing foreign financial institutions to participate in the restructuring and disposal of assets.B. Offshore IPOs of the Big Four BanksIn order to improve the Big Four banks’ capitalization, these banks were allowed by the Chinese government to be listed in capital markets. By drawing in more capital these banks not only become cash-rich but also more disciplined subjecting themselves to international standards of corporate governance and accounting rules.C. Money Injection and China HuijinBonds issued by the MOF and foreign reserves held by the PBOC were the two main sources of funds used to rebuild the commercial bank’s balance sheet.The PBOC relaxed the reserve requirement (or cash reserve ratio) from 13 percent to 9 percent, freeing up about 270 billion yuan bank liquidity. The additional liquidity used by the Big Four banks was to buy government bonds issued by the MOF. The receipts of the bonds purchased by the Big Four banks were transferred to the Big Four banks as fresh equity capital by the MOF. The capital adequacy ratios of the Big Four banks significantly improved with changing the asset liability position in the balance sheets by the recapitalization. The foreign reserves were mainly injected into the commercial banks through a state-owned company called the Central SAFE Investments Company (or Huijin). Central Huijin is controlled by the State Council, China’s cabinet, and is dedicated to ‘inject equity to the state-owned financial institutions.’ The MOF provided Huijin’s initial capital, but the PBOC was also another important stakeholder, injecting foreign reserves into Huijin as equity. Huijin in turn injected the equity into the commercial banks, with these equity infusions totaling approximately USD 156 billion by 2012. Huijin made cash investments totaling USD 45 billion in CCB and BOC in late 2003 and USD 15 billion in ICBC for a 50 percent holding in 2005. These investments enhanced the capital adequacy ratio of these banks and allowed them to provision some of the NPLs on their balance sheets without going bankrupt. By 2005, Huijin had become the controlling shareholder of the Big Four banks on behalf of the state and enjoyed majority representation on the boards of directors of CCB and BOC and together with the MOF, ICBC, CDB and ABC.D. Foreign Equity Injection: Introducing Strategic InvestorsAnother measure for reducing NPLs was the introduction of ‘strategic investors’, that is, foreign investment banks or investment companies. They injected their money into the commercial banks as equity before the Chinese banks went public, and therefore allowed them to write off more of their NPLs. This also helped achieve the government’s purpose of bringing in needed foreign expertise as China’s banks became more commercial in orientation.Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Allianz Group and American Express invested USD 3.78 billion in ICBC in exchange for 10 percent of ICBC, which was announced on January 27, 2006. Goldman Sachs alone bought a 4.9 percent stake in ICBC for USD 2.58 billion. On August 26, 2004, BOC was entirely reorganized from a purely state-owned commercial bank, which marks a key step in the reorganization of China’s Big Four banks into non-solely state-owned enterprises. In 2005, the Royal Bank of Scotland led an investment of USD 3.1 billion for a 10 percent stake in BOC with the Royal Bank of Scotland itself investing USD 1.6 billion and the rest being invested by Merrill Lynch International and the Li Ka-shing Foundation.Both Qualified Foriegn Institutional Investor (QFII) and Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII) are transitional programs given the fact that foreign investments in China are restricted due to foreign exchange control. The quota, products, accounts, and fund conversions are strictly monitored and regulated.The QFII scheme, set up in 2002, allows foreign institutional investors such as funds who meet certain qualifications to invest in a limited scope of cross-border securities products such as China’s yuan-denominated A shares in the context of incomplete free flow of capital accounts. The RQFII program, introduced in 2011, gives investors access to offshore RMB to buy mainland-traded stocks. It allows the use of RMB funds raised in Hong Kong by the subsidiaries of domestic fund management companies and securities companies in Hong Kong to invest in the domestic securities market. Through the QFII and RQFII schemes, investors can invest in all the securities listed on China’s two Stock Exchanges, which include listed bonds that are mostly corporate bonds as well as bonds traded on the China Interbank Bond Market (CIBM), subject to the CSRC approval, filing with the PBOC and the quota granted by SAFE. Table 2 compares the key perspectives of QFII and RQFII.

In September 2019, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), China’s foreign exchange authority, scrapped quota restrictions on QFII and RQFII, giving global trader’s unfettered access to the world’s second-largest capital market which is a new move in China’s financial liberalization.QFII and RQFII may theoretically engage in activism in listed companies and the shareholder activism may help improve corporate governance. Activist shareholders may influence the effectiveness and efficiency of corporate governance through their voting rights and charter power. Voting, based on the shares, is the primary channel through which shareholders express their view, by supporting or opposing resolutions, on the way a company is managed and governed. In the US context, hedge funds, mutual funds and pension funds are carrying out shareholder activism though may have different strategies and expectations over activist statics, investment returns, corporate governance and intellectual property protection, among others. Given the dominance of state ownership in listed companies, shareholder activism is technically neither necessary nor feasible. It is not necessary as the state, being the controlling shareholder, has a final say over personnel appointment of executives and managements. It is not feasible for other shareholders as they may be marginalized by the state owners and their voting power and shareholders are cosmetic only. However, QFII may differ from other local shareholders. As foreign shareholders, QFIIs are supposed to enjoy more preferable treatments, termed as supranational treatments, under the foreign investment law and the company law. The reasonable expectation is that QFIIs may engage with portfolio companies owing to their rich experience and strong financial backup. The longer lockup period also acts as a mechanism to align QFIIs’ interests with the portfolio companies’ interests as their distance from short-termism means their unlikelihood of walking away any sooner. QFIIs’ longer stay with the portfolio companies only gives them two options: either hang around with the existing corporate governance practices or penetrate into the companies with some changes. The question then is the availability of adequate and suitable mechanism to allow the QFIIs’ execution of activist measures. There are six kinds of mechanisms that the institutional investors may rely on to carry out institutional activism. Shareholder proposals, jawboning, targeting announcements, public censure, dialogue and coalition are developed and seen in the US market and now are spread to other places across the world. But the upsetting truth is that shareholder activist campaigns are rare in China. The Chinese law including portfolio limits, insider dealing liability and disclosure rules required against institutional investors, making QFIIs powerless and their consortia weightless, hinders the expansion of these activist measures to be executed in the domestic stock markets. Shareholders holding more than 3 percent of shares, either individually or jointly, in a company can submit a shareholder proposal to the shareholders meeting. This threshold of 3 percent however is higher than the 1 percent threshold required in the US Limits are imposed by the CSRC on the extent of shareholdings by institutional investors in listed companies. A fund cannot hold shares with a market value of more than 10 percent of its own net assets in a single portfolio company. This diversification rule ensures a fund’s diversified portfolio so as to limit its exposure to the price risk of a single stock. An institutional investor holding more than 5 percent of a company’s shares is an insider under the law and therefore is subject to trading restrictions on the shares it holds. When this insider shareholder sells those shares within 6 months of purchase, or repurchases any shares sold within 6 months, the profits from trade to that company must be forfeited. While this short-swing profit forfeiture rule is designed to prevent the insider shareholder from taking advantage of its insider role to trade on inside information and profiting at the expense of minority shareholders, the chilling effect of this rule is the deterrence effect. The insider-dealing liability is also imposed in the form of economic penalties and administrative sanctions.The insider shareholder is also subject to disclosure obligations. It must notify the CSRC and the stock exchange and inform the company and the public within 3 days of reaching the 5 percent threshold. Shareholders must disclose each increase or decrease of 5 percent or more of the shares of the company to the CSRC, the stock market, the company and the public. The purchase or sale should not be conducted within 5 days including 3 days for filing with the CSRC and the stock market, and notifying the company and the public, and 2 days after the disclosure. This disclosure requirement ensures the transparency of the insider shareholder’s identify, stock and monthly trading record in the 6-month period leading up to the disclosure.Shareholders acting in concert (meaning their forming a shareholder consortium through agreement or other arrangements) are subject to more onerous information disclosure obligations under which they need to publish their identities, the purpose of shareholding and their stake in shares, stake-holding, time and method of stake-holding, the relationship between themselves, and portfolio companies in the 24-month prior to their stake-holdings. They are subject to administrative sanctions and financial penalties if there are any false statements, misrepresentations or material omissions. Further, holding 30 percent of all shares of a portfolio company mandates shareholders acting in concert to initiate a mandatory takeover bid, either partial or full, for the company’s shares.Thanks to these structural or regulatory defects discussed above, QFIIs may only help bring in the liquidity, instead of sound corporate governance experiences, into the capital markets. Chinese listed companies are highly concentrated and the majority shareholders (in most cases SOEs or family-controlled owners in other cases) hold controlling shareholdings at an average rate of 55-60 percent in the past decade, which can easily block or defeat the proposal striving for changes made by other non-controlling shareholders. QFIIs’ passiveness in statics matches the general pattern of other non-state investors in the Chinese context. Controllers add structural difficulties to outside challengers. Without such managerial experiences, the domestic stock market remains rudimentary and the legal and regulatory system is then left behind.

III. NEW MARKET-ORIENTED APPROACHES TO NPLS

A. Debt-for-Equity Swap and RestructuringThe Chinese government has been implementing an equitization policy to alleviate excessive debt. While this may technically lower the NPL ratio, it may delay the disposal of NPLs and prolong the downward phase in China’s growth rate.1. Debt-for-Equity Swap Program. — By the end of 2015, the NPLs of Chinese commercial lenders stood at 1.27 trillion yuan, equal to 1.67 percent of all outstanding loans. The economic reason for this NPL rise was that the loans to the steel industry and other sectors turned sour due to the economic downturn. Since April 2016, debt-for-equity swaps have been hailed as a means of resolving Chinese banks’ NPL problems. The plan to dispose of bad loans was to turn banks’ NPLs, worth 1 trillion yuan, into equity in the borrowers. Although the swap program drew attention, it has underperformed. The swap was developed in the mid-1980s as a response to the Latin American debt crisis. Swap, as a debt-repackaging mechanism, is beneficial to all the stakeholders involved in the transactions albeit some drawbacks. The swap program was not new in China and was used by the government to restructure large SOEs and to spin off NPLs from the highly distressed banks to AMCs in the 1990s. The SOEs in the 1990s suffered huge deficits at the average ratio of 25-30 percent and the annual loss of the SOEs was 35-48 billion yuan. Bad loans had a series of impacts on the SOEs, banks and the real economy. The swap program was introduced to bail out distressed SOEs and banks. Some regulations and policies were passed to provide an outline of the swap program including the Opinions on Several Issues concerning the Implementation of Debt-to-Equity Swap issued by the State Economic and Trade Commission and the PBOC in July 1999 and the Decision of the Central Committee of the CCP on Major Issues concerning the Reform and Development of State-owned Enterprises promulgated by the Fourth Session of the 15th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee on September 22, 1999. Four AMCs in the period of 1998 and 2000 purchased the NPLs from the banks and then converted them into equity in the defaulting borrowers, and became shareholders in the debtor companies. It was estimated that over 1.4 trillion yuan NPLs were swapped into equity. Nevertheless the hoped-for 10 percent recovery rate was never achieved. Banks were largely path dependent by extending loans to borrowers with poor record of bad loans.After the global financial crisis, there has been an increase of debt and NPLs generated in the banking system. The leverage ratio of non-financial institutions rose from 157 percent to 217.3 percent during the period from 2008 to 2014. Commercial banks’ NPLs amounted to 1.27 trillion yuan by 2015. As part of the de-leveraging exercise, the government came back with the debt-for-equity swap program to reduce the high debt ratio not only in the banking system but also in the real economy.Under the swap, a debt holder receives shares in exchange for cancellation of the debt. The debt-for-equity swaps are put in place to lower corporate leverage ratios, and to help struggling borrowers stay in business. In addition, the borrowers can increase their capital. A creditor may convert its rights over the loan into the equity of the debtor, and then realize returns from a future sale of equity, trade sale, or other distributions from the debtor. Creditors may also obtain capital gains and dividends after the borrowers recover from their distresses. Turning creditors to shareholders allows lenders to monitor the borrowers more effectively given its effective participation in corporate governance. Different from the 1990s, this time, the swaps are largely led by the banks, which would set up their own AMCs to dispose of debts. Bank-run swaps are more effective as banks monitor debtor companies through covenants in the loan agreements to restrain the moral hazard in borrowers’ risk-taking activities. Prior to the swaps, banks possess some tools such as foreclosure on collateral, reorganization or legal actions to monitor, which is important to the bank-dependent firms’ corporate governance. After the swaps, banks become controlling shareholders (in the sense of voting rights attached to shares though such shares may not be majority) and have an impact on corporate governance and performance. While banks are facing both competition pressure from their peers and capital adequacy pressure, their self-interest is to dispose of NPLs more effectively compared with state-controlled AMCs which are furnished with political targets to achieve. Given the fact that the banking sector’s current NPL ratio is not as high as the one in the 1990s, the swaps should be conducted without excessive government intervention. Banks, as the creditors and collateral assets handy, are in the best position to negotiate and enter into more favourable terms for the swaps.However, the swaps may not necessarily be safe for banks’ depending on the corporate’s likelihood to recover from its financial distress. Insolvency may turn the lender to a worse scenario as a shareholder ranks the last in the priority order of distribution of outstanding assets. In the case that the borrower does not recover from its distress, banks holding non-performing equities face more risks as stock prices may fluctuate more than debt. Besides, banks and AMCs usually have more appetite for fixed-income debt than equity. If the swapped debt is in good standing and there is no default, investors then have no incentive to forgo stable fixed returns for uncertain equity gains. For the borrower, converting debt into equity on the balance sheet or ‘financial engineering’ does not boost its earnings. Most of the borrowers in the swaps are distressed companies with limited prospects for recovery without simultaneous corporate restructuring aimed to restore profitability. Structural transformation of these distressed companies usually is time consuming. From the regulatory perspective, there is uncertainty about the scope of borrowers. There has been no clear definition of borrowers which would be targeted for this swap program. This easily creates some confusion and discretion. The Company Law was amended in 2018 to allow the company to repurchase shares from the shareholders. However, some regulatory restrictions may prove burdensome to third-party investors (who are involved in the swap deals for returns but not for policy considerations). For instance, the CSRC rules governing the issuance of new shares require pricing to be no less than 90 percent of the market value which may discourage investors to participate in the swaps if they want more pricing flexibility. The consent of the board, shareholders’ meetings and regulators may be too lengthy to make the transaction economically viable. China’s market-based debt-to-equity swap program started in 2016. In the first two years since the swap program was launched, little progress has been made in expanding the scale of the program and improving the execution of the signed swaps. By the end of 2017, only 14 percent of signed swaps by value had been executed compared with China’s corporate loan balance of 132 trillion yuan (USD 19.11 trillion). The value of executed swap compared with 143.1 trillion yuan (USD 20.72 trillion) in nonfinancial corporate loans outstanding by the end of April 2019 was minuscule. In addition, most swap projects were with SOEs. Private enterprises were largely bystanders in this period due to the highly uncertain prospects of default. As the swap program underperformed, the program has been extended from the state to private sectors.The latest data, released by the State Council show some improvements in the swap program. The program has expanded in scale since 2017, and by the end of April 2019, 40 percent of the signed swaps by value had been executed, a leap forward from 14 percent at the end of 2017. Meanwhile, more private firms are getting involved in the program, either as target companies or as equity investors in some heavily indebted SOEs. The share of executed swaps involving private enterprises, though still too small, was 6.5 percent of all signed swap contracts (24 of the 367 signed contracts) in April 2019, compared with 1.2 percent (1 of 81 signed contracts) at the end of September 2017.China’s implementation of the debt-for-equity swap program has improved in a gradual pace. Yet, the debt-to-equity swap program has done little to cut China’s high leverage. Though the executed value has gone up rapidly over the past three years, its overall size is still extremely limited. 910 billion yuan (USD 131.75 billion) in the executed value of debt-to-equity swaps, compared with 143.1 trillion yuan (USD 20.72 trillion) in nonfinancial corporate loans outstanding by the end of April 2019, is still minuscule.Market-oriented debt-to-equity swaps are mainly concentrated in such industries as steel, coal, chemicals, and equipment manufacturing, and are dominated by the SOEs, especially the local SOEs. From 2016 to the end of February 2019, the total amount of market-oriented debt-to-equity contracted projects reached 2 trillion yuan in 420 contracted projects. In total, 630 billion yuan of funds have been paid in 337 projects, and the capital availability rate was 31.07 percent.2. Legal Framework and Mechanisms. — The first is the State Council Guiding Opinions of 2016. To address the growing NPLs faced by Chinese banks, in September 2016, the Chinese government expressly encouraged commercial banks to carry out debt-to-equity conversion through the AMCs and other acquirers of NPLs. In October 2016, the State Council issued the Guidance Opinion on Marketizing the Bank Debt-for-Equity Swap (hereinafter referred to as the Guiding Opinion). Both onshore and offshore investors are allowed to process the debt-to-equity swap by making the application to the State Administration of Industry and Commerce (SAIC), the company registrar, having jurisdiction over the debtor.In addition, to complete the debt-to-equity swap process: (a) the creditor and the debtor should enter into a debt-to-equity swap agreement; (b) the creditor’s rights should be evaluated by an independent and qualified accounting firm or evaluation institution; (c) the target company (debtor) should complete the registration with the SAIC for the change of shareholders, capital increase and transformation of the company from domestic company to foreign-invested company (if the creditor is a foreign investor).There are two notable features of the Guiding Opinion, that is, marketization and legalization. The characteristics of the marketization (i.e. exposing the process to market forces) are mainly reflected in the following aspects:First, the debt-for-equity swap should have the follow prerequisites: (a) the enterprise should have good prospects for development, feasible enterprise reform plan and difficulty-relief efforts; (b) the enterprise’s production equipment, products and competence must conform to the national industrial development direction; (c) the enterprise should have advanced technology, marketable products, environmental protection and work safety conditions; and (d) the enterprise should have good credibility without records of improper activities. The government encourages outstanding enterprises which have temporary obstacles but good prospect for the development to start bank debt-for-equity swap. These enterprises include the enterprises which have difficulties because of periodic fluctuation, the newly-emerged growth enterprises that have high liability and the lifeline enterprises which have strategically dominant position in national economy. Some enterprises are prohibited from being part of the debt-equity swap scheme: zombie (ineffective and unpromising) companies with malicious evasion of debt; enterprises without clear debtor-creditor relationship and credibility; and companies which may cause over-capacity of production.Second, the market-oriented debt-equity swap should be carried out through an executing institution. Except otherwise as determined by the State, the bank shall not directly convert debt to equity. The plan prevents banks from directly swapping NPLs, with conversions to be handled by ‘qualified implementation agencies’, which are tasked to convert the loans into equity. The AMCs, insurance AMCs, state-owned capital investment and operating companies and other types of implementing agencies are encouraged to participate in the market-oriented debt-equity swap. The government supports banks to make full use of the existing eligible institutions, or to apply for the establishment of new institutions to implement the debt-for-equity reform. The key players in the swap programs are the Big Four AMCs and over 50 other local AMCs set up by multiple joint stock commercial banks and city commercial banks. Four largest AMCs had executed 70 percent of the signed swap projects (254 of the 367 signed swaps) and 44 percent of the signed swap value (400 billion yuan of the total signed value of 910 billion yuan) by the end of April 2019, of which around 250 billion yuan (USD 36.19 billion) was raised from private equity and government-guided funds and local governments and the rest from the Big Four banks’ own balance sheets.Third, the pricing is a major challenge. If the market forces function well, swaps can be priced in a fair manner. The conversion price is to be ‘market-oriented’ and negotiated by banks, investors, debtors and the implementing agencies without external influence. Banks, enterprises and implementing agencies could determine prices and conditions of assignment of credit. For situation involving multiple creditors, largest creditors or creditors who initiate market-oriented debt-for-equity swap could form a creditors’ committee to coordinate. With approval, it is allowed to determine the conversion price of SOEs by reference to the transaction prices of the stock market and allow the price of the conversion of state-owned unlisted companies to be determined with reference to the trading price of stock market. However, there is a lack of key pricing infrastructure; state intervention may restrict the role of market forces in determining fair prices of the swaps, turning away prospective investors. The Beijing Financial Assets Exchange was in July 2018 charged with launching a reporting platform for debt-to-equity projects to resolve the information asymmetry issue. This may be a means to shape a market-oriented pricing mechanism in order to attract more non-state capital into the swaps.Fourth, the scheme was designed to be market-oriented to raise debt-equity funds. The funds needed for the debt-for-equity swap could be raised by the qualified implementing agencies in a variety of market-oriented ways, including encouraging the executing institutions to lawfully raise capital from investors, to support the executing institutions to issue specific financial bonds for market-oriented debt-to-equity swaps, and simplify the approval procedures.Fifth, allowing the equity holders to transfer their positions to other investors as regular investors may trade their shares. If the executing institutions have an expectation of equity withdrawal, it may negotiate with the enterprise to withdraw the equity held by the enterprise. If a debt-for-equity enterprise is a listed company, the debt-for-equity swap can be lawfully transferred out. At the same time, the securities regulatory requirements such as the lock-up period shall be observed. If a debt-for-equity enterprise is an unlisted company, this company should be encouraged to use the way of merger and acquisition, regional equity market transactions and other channels to achieve the equity transfer out. Legalization is mainly reflected in the following aspects. First, to standardize equity changes and other related procedures. The debt-for-equity swap enterprises shall complete the business registration or change registration formalities in accordance with the law, such as the establishment of the company, the alteration of the shareholders, and the reorganization of the board of directors. Second, to protect the rights of shareholders in accordance with the law. After the implementation of market-oriented debt-equity swap, it is necessary to ensure that the executing institutions enjoy the rights of shareholders, including participating in making significant business decisions and equity management within the scope of laws and the articles of association. The implementing institution of the bank shall determine the reasonable shareholding in the debt-for-equity swap enterprise and shall bear the limited liability according to the Company Law.The second is the CIRC Pilot Management Rules for Financial AMCs. In accordance with relevant laws and regulation, a debt-for-equity swap is allowed under one of the following circumstances: (i) the creditor has already performed its contractual obligations and has not violated any laws, regulations, administrative decisions or the prohibitive provisions of the debtor’s articles of association; or (ii) the proposed conversion has been approved by effective court judgments; or (iii) the proposed conversion through bankruptcy reorganization plans or settlement agreements has been approved by court.For the Chinese AMCs and banks, there are three exit options for debt-for-equity shares: direct sales to investors, IPO listing, and equity buyback by the SOEs. The timing and likelihood of the latter two options are highly uncertain, while a direct sale to investors is the fastest way for the AMCs and banks to convert their equity rights into cash.Stressing the ‘market based commercial approach’ of the initiative, the scheme is put in place to ease the debt burden on companies suffering from short term difficulty whilst avoiding bailout for zombie companies. The government, having tried up cash, will not be willing and able to bail out in the case of any losses. The debt-for-equity swap scheme also suggests that de-leveraging is a tough mission not only for banks and indebted companies but also for the government.Debt-to-equity swap is a resolution for creditors to deal with NPL issues. The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission instructed the SOEs to cut their liability-to-asset ratio by two percentage points from the 2017 level by 2020. The SOEs tried to meet the de-leveraging target by using swaps, issuing perpetual bonds, and selling assets if necessary. As of March 2017, more than 430 billion yuan of swaps deals have been signed since the launch of the new scheme with 40 billion yuan debt turned into equity. According to the NDRC, as of January 2019, Chinese companies had committed to doing more than 2 trillion yuan of swaps. Swaps offer an additional means to reducing corporate leverage and improve corporate governance (in the sense that private capital may be introduced into more SOEs). Unless the debt-for-equity swap program fundamentally improves the operation of a SOE, this measure is merely a mechanical fix to the capital structure and will have little impact on cash recovery over the long-term.B. Bond Market: China Interbank Bond Market and Exchange-traded Bond Markets in Shenzhen and ShanghaiChina’s bond market is the third largest in the world which is in total worth of USD 11.17 trillion by the end of 2018. The bond market grew from 17 percent of GDP in 2000 to 90 percent in 2017. The bonds in 2017 accounted for one third of total financing, making the bank lending below 50 percent of total financing. Foreign investors hold about 800 billion yuan or 1.3 percent of the total. However, it is underdeveloped and its original purpose was to fund government projects. Needless to say, most bonds are issued by entities linked to the government. In 2016, companies and the government (including policy banks, the central government and local governments issued 15 trillion yuan and 35 trillion yuan (exclusive of 16 trillion yuan bonds issued by the SOEs) worth of bonds respectively.It is commercial banks that ultimately buy most of bonds. Government bonds account for 26 percent of the Big Four banks’ total assets on average. Commercial banks synchronize their fixed-income investments such as bonds and money market funds to avoid bank runs. Government bonds are liquid assets which are easy to sell and convert into cash, and can be good asset portfolio.1. Overview of Bond Market. — The bond market has been an important component in China’s financial market and the main channel of direct financing for corporates. China’s bond market was shaped by the demand from companies and other issuers for less expensive capital than banks were willing to offer as well as the need to reduce excessive risk concentration in the banking system. As investors are to hold corporate debt, risk can be diversified so as to shift the burden from the banks. China’s bond markets have witnessed huge insurance volumes, foreign investment, a wide scope of products, and standardized underwriting procedures. However, China’s bond markets are captive to a controlled interest rate framework and banks as predominant investors. The bond markets are heavily regulated in the sense that they are operated in a controlled environment in which prices and investors are managed to suit the government’s political agenda. Banks are the dominant underwriters of all bonds including central government bonds, PBOC notes, policy bank bonds and bank subordinated debt. Meanwhile, banks monopolized bond trading on the stock exchanges. At the end of 2018, the total volume of outstanding bonds in China’s bond market reached 85.7 trillion yuan (about USD 12.5 trillion), about 95.2 percent of China’s GDP. China’s bond market, as demonstrated in Figure 2, is comprised of an over-the-counter (OTC) market and exchange market. The OTC market, as a secondary market, includes an interbank market and commercial bank OTC market, and the exchange market consists of the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE). The secondary market was created on the exchanges to expand the funding sources.

Figure 2: Bond Market Framework

While the segments of the bond market are able to offer a wide range of products and maturities including government and quasi-government bonds, credit bonds, financial bonds issued by financial institutions, Treasury futures and green bonds, the bond market as a whole is characterized by market fragmentation. The over-the-counter (or interbank) bond market, accounting or 90 percent of bond financing, and the exchange bond market are discrete, with different trading mechanisms, market participants, and bond varieties. They are traded on different platforms, subject to different rules and regulated separately by different institutions and authorities responsible for registration, custody, and settlement. Market fragmentation results in low liquidity and decentralized trading, thereby impeding market depth and efficiency. Against this backdrop, regulators have taken measures to promote the bond market connectivity in recent years. In September 2018, the PBOC and the CSRC announced the promotion of the gradual unification of rating qualifications in different markets. In December 2018, the PBOC, the CSRS and the NDRC confirmed that the CSRC is responsible for the unified law enforcement against illegal acts in both the interbank bond market and exchange bond market. These policies show that China’s bond market has been progressing towards and unification. In practice, there is a daily price fixing for debt securities, which is an official price, set for traded products by the China Government Securities Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation, an entity owned by the PBOC and the depository for all bonds traded in the interbank market. Due to the government control over the bond market, there is an absence of active market trading. Owing to the light trading volume, the bond yield curves cannot be used as meaningful benchmark for corporate debt underwriters or corporate treasures. Even with limited cross-border portfolio flows, it was proved an increasingly sensitivity of the yield curve to global factors. This suggests that domestic bond yields have been under the influence of monetary policy change in advanced economies and market condition change in global markets.2. Structure of Issuers and Investors. — Issuers in China’s bond market include governments and governmental institutions, as well as financial institutions and non-financial corporates. Like developed markets, China’s bond markets have a variety of products including government bonds, commercial paper, medium-term notes, corporate bonds, bank subordinated and straight debt, asset-backed securities. These bonds can be traded for cash or sold forward, and interest risk can be hedged through swaps. As for bond varieties classified by payment modes, there are zero coupon bonds, discounted bonds, fixed interest rate bonds, floating interest rate bonds, and lump-sum cleared bonds. To satisfy diversified financing demands, many innovative types of bonds have been issued in recent years, such as green bonds, Belt and Road bonds, as well as innovative and entrepreneurial corporate bonds. The public sector dominates and accounts for over 60 percent of the bond market, comprising sovereign, policy bank, and local government bond markets. At the end of 2018, government bonds, with maturities ranging from 3 months to 50 years, accounted for 40.4 percent of total outstanding bonds, among which 17.4 percent were Treasury bonds and 21.1 percent were local government bonds. Market liquidity of government bonds is thin. Meanwhile, the outstanding amounts of corporate credit bonds and financial bonds accounted for 20.9 percent and 23.7 percent respectively. Banks hold 70 percent of the bonds until maturity and even secondary market trading. Even though the market liquidity and trading are weak, the linkages between the government bond yields, macroeconomic developments and global financial market conditions have been stronger than before.The number and types of investors in China’s bond market have been expanding in recent years while the structure of investors tends to improve. But by far commercial banks still dominate the market having over 70 percent market share. Investors in the interbank bond market are qualified non-bank financial institutions and non-financial enterprises, commercial banks, policy banks, and QFII/RQFII with the approval of the PBOC for interbank access. Investors in the exchange bond market are non-bank financial institutions, non-financial enterprises, listed commercial banks, QFII/RQFII with the approval of the PBOC for interbank access, and individual investors. Investing in Chinese bonds is a low-risk investment as they are backed by the government.The fact that the dominance of commercial banks in the bond market, while stabilizing the market, results in a low liquidity of the secondary market as commercial banks are more willing to hold bonds to maturity, which to some extent, hinders the transfer of risks from the banking sector to other sectors. However, with the gradual opening-up of the bond market and the entry of other types of investors, the proportion of bonds held by commercial banks has showed a tendency to decline. The change has emerged to the market structure. Currently, funds which tend to trade in the market more actively than other investors are in the tendency to become the largest holder of credit bonds issued by firms in different segments.3. How Is China’s Bond Market Regulated? — Modeled after the regulatory structure in the US wherein issuers of bonds are required to have a credit rating agency, an underwriter, a prospectus, and a filing with the regulator, the PBOC in 2007 set up an industry association, the National Association of Financial Markets Institutional Investors (NAFMII), to manage the bond market. The debt issuers are more transparent in the sense that their financials, approval documents and prospectus are available online on China Bond and NAFMII websites. The regulatory framework of China’s bond market is also fragmented. China’s bond market has been developing from government planned to market-oriented and from unorganized to well-regulated. Throughout this process, the government has undertaken the role of coordinating interests and establishing fundamental systems. The emergence of different bond markets and bond varieties were promoted by different government departments and this led to a fragmented regulatory framework.(i) Regulation of trading floors: The regulators of the interbank bond market and the exchange bond market are the PBOC and the CSRC, respectively. Both markets have set specific requirements on information disclosure in terms of disclosure time, disclosure of major events, and so on. The information disclosure on enterprise bonds is regulated by the NDRC.(ii) Regulation of clearing, settlement, and custody: There are three custody institutions that are regulated by different regulators. The opening of securities accounts for investors in the interbank bond market is in China Central Depository & Clearing Corporation Limited or Shanghai Clearing House, while China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation Limited are responsible for the custody and settlement in the exchange bond market. The clearing and settlement mechanism applied in the interbank market includes full bilateral clearing and net amount centralized clearing. The former usually adopts the settlement method of DVP while the latter usually adopts ‘central counter party’.(iii) Regulation of rating agencies: The regulation of rating agencies is fragmented as well, which to some extent leads to the inconsistency of rating standards in different sub-markets. In September 2018, the PBOC and the CSRC announced the promotion of the gradual unification of rating qualifications in different markets in order to promote the unified regulation of the credit rating industry. Together with the National Association of Securities Dealers, they will form a ‘concerted action person’ to regulate rating agencies, showing that China’s credit rating industry has formally entered the era of unified regulation.The regulatory framework of China’s bond market together with related systems has played a positive role in preventing market risk and boosting market development. But the existing regulatory system also has limitations mainly reflected by the lack of a unified legal system as well as by the existence of multiple regulatory systems with different morals, operation mechanisms, and styles of regulation in different trading floors with different regulators. This hinders the efficient allocation of financial resources, the unified prevention and control of risks, and the opening-up of the bond market. In this context, China’s bond market will tend to be regulated in a unified way step-by-step, and recent policy have confirmed these tendencies.China’s backward bond market has inherent risks. It does not absorb or resolve debt but accumulate risks in relation to debt. Banks are the major subscribers of bonds. Making up around 25-30 percent of the total assets of the Big Four banks, bonds not only bring negative interest spreads to banks but also expose banks to market risk. Likely, imprudent or policy-driven lending is likely to increase banks’ credit risk. Consequently, banks’ lending spree will create more asset bubbles, stock market booms and NPLs, which in turn brings out a new cycle of AMCs, PBOC credit support, the government’s stimulus package or quantitative easing. Although these measures may contain the NPL problem, they will not resolve the NPL problems.IV. EXPERIENCE AND LESSONS: IS MARKET ENOUGH FOR NPL DISPOSAL?China’s nonconvertible currency, managed exchange and interest rates, and the need to maintain a high GDP growth rate create inevitable demand for new capital. The huge demand for new bank capital eventually depends on international and domestic capital markets. China’s banking sector in 2008 was around USD 9 trillion and turned to USD 39 trillion by the end of June 2018. It is now equivalent in size to the entire US, EU and Japan banking sector combined. Two thirds of this increase came in the form of loans and bonds, which are traditional sources of credits. The remaining one third came from non-traditional or shadow sources of credit such as P2P companies, non-bank financial institutions. China’s credit growth is on a dangerous trajectory, with increased risks of a disruptive adjustment and/or a marked growth slowdown. To a certain extent, China’s high savings rate, current-account surplus, small external debt and various policy buffers may help to mitigate the risks.The Chinese government has built up a full international capital market model to resolve NPLs. This so-called multiple-tiered capital market model involves basically all financial markets ranging from the capital market and bond market to offshore RMB market and even shadow banking sector. Companies were given the opportunity to choose between banks and debt markets. Nevertheless, these markets are heavily managed and do not play the same function as these markets in other market economies. Meanwhile, China’s closed financial system isolates China from the global systemic risks, helping China counter global financial market’s instability. China’s debt crisis is unique in the sense that it has not incurred a huge amount of sovereign debt, which would have damaged China’s economy like the sovereignty debt crisis hit other economies. Nevertheless, the state ownership of China’s banking system may lend an implicit guarantee to the soundness and safety of China’s financial system as a whole, which is costly to the government due to the moral hazard issue. In China’s financial safety net, apart from the lender of last resort, failure resolution and regulatory framework, there is also a guarantor of last resort being the government as the ultimate guarantor for the bank run and regulatory failure. This may justify the Chinese government’s latest efforts to put the deposit insurance scheme and bank bankruptcy system in place to discipline the risk-taking banks and investors. These policy moves may suggest that the regulatory focus be placed on the supply side. China needs to cut the economy’s dependency on debt not only for its own best interest but also for the good of global rebalancing.Chinese banks face challenges on several fronts. Chinese banks have their structural exposure to the old NPL portfolios left behind in the 1990s. The new NPLs arising out of the lending spree right after the global financial crisis are mounting risks to these banks. Policy loans in commercial banks are, by definition, NPLs. The Big Four banks embarked on commercialization in the past four decades but are turning themselves into policy banks. In terms of the securities portfolios, Chinese banks are exposed to interest rate-related and credit-induced write-downs in the value of the fixed income securities. Chinese banks’ difficulty of shifting debt burden in other markets is that the counterparty is likely to be other banks.China needs to accelerate the NPL transfer process from banks to AMCs and rely more on the competitive bidding process among AMCs. Where necessary, state banks should be allowed to sell NPLs below book value to third-party investors. In order to dispose of the NPLs more effectively, the AMCs can be awarded with immediate, special legal power for collection, foreclosure, and restructuring. In March 2020, the China Banking and Insurance Regualtory Commission (CBIRC), the combination of CBRC and CIRC, announced the news that the fifth AMC at the national level, Yinhe AMC, is set up on the basis of Jiantou Zhongxin Asset Management Co., Ltd., Huijin and Zhongxin Securities own 70 percent and 30 percent equity each in the company. The set-up of a new AMC may suggest the CBIRC’s intention to rely on this new AMC to shift the NPLs.To meet demand from domestic and foreign investors as well as sustainably manage local capital market, the Chinese government is deploying two strategies: opening credit markets to foreign investors and bringing integrity and efficiency to the Chinese domestic debt market through standardization.China’s bond market reforms are consistent with China’s goal of a more open, market-oriented economy over the long term. Structural reforms may not only improve integrity and efficiency of China’s debt market but also accelerate foreign participation and sustainable growth.The Chinese government has undertaken systemic deleveraging through a multi-tiered capital market approach, relying on all sorts of financial markets for the debt diversification and rollover (or maturity transformation). Its strategy still largely depends on the government’s policies rather than market forces. However, the longer chain of intermediation and the higher level of complexity in financial markets may create a new source of systemic risks. Fragmentation nodes require a new thinking of regulatory tools to reduce the length and complexity of the chain connecting investor and investment. Apart from disclosure, simplicity may be effective in addressing the sources of systemic risk caused by financial innovation and fragmentation.China also needs to improve the legal framework for foreclosure, liquidation and reorganization, and streamline the regulatory approval process for bulk sales/securitizations and limit the approving party to no more than one or two organizations. Market-orientated measures are important. However, some reforms deployed by the Chinese government are likely to avoid deleveraging. New credit continues to outstrip deposit growth. The most troubling aspect of China’s debt problem is the surge in the more opaque and less regulated shadow banking sector.NPLs are contaminating banks’ balance sheets and the wider economy. Securitization may be the solution. However, success depends on improvements in servicing, enforcement and foreign involvement. China should have a securitization law to enable the creation of SPVs and true sales of assets. The law should clarify tax and accounting treatments for SPVs/trusts as well as improve the regulatory and legal process to retain foreign participation in the market.Maintaining a large state-owned economy means political control may work more effectively than economic liberalization policy. However, it also suggests low economic efficiency and large cost to the government in allocating resources, potentially leading to a legitimacy crisis if anything goes wrong with the macro economy. Any attempts to deal with China’s debt burden requires hard decisions, including shuttering less productive SOEs by forcing them to realize losses, reining in shadow banking, capping credit growth, adjusting lending rates to account for risk, and accepting lower levels of GDP growth.